Falklands telegrams reveal UK response to invasion

- Published

Previously secret telegrams from the time of Argentina's Falklands invasion in 1982 reveal the scramble to find a ship big enough to send UK troops to the South Atlantic, the burning of sensitive papers and intense diplomatic efforts to stop French-made missiles reaching Buenos Aires.

A record of the communications is contained in government files just released by the National Archives in London under a 30-year rule.

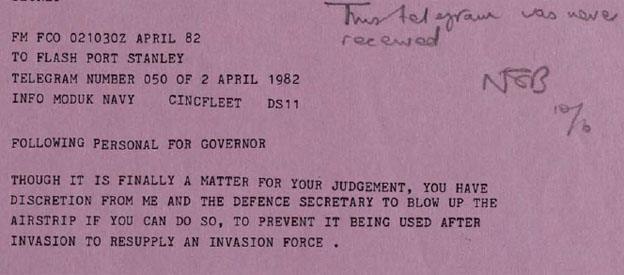

Argentine forces landed on the Falklands on the morning of 2 April. At 10:30 GMT, Britain's Foreign Secretary, Lord (Peter) Carrington, sent an urgent telegram to the governor: "You have discretion from me and the defence secretary to blow up the airstrip if you can do so, to prevent it being used after invasion to resupply an invasion force".

However, communications between London and the Falklands capital, Stanley, had become intermittent, and a handwritten note on the telegram records: "This message was never received."

Extract from Lord Carrington's telegram authorising the destruction of the airstrip

By the following day, 3 April, the governor, Rex Hunt, had been forcibly evacuated by the Argentines to Montevideo.

From there, he gave the Foreign Office a rundown of his final hours at Government House in Stanley.

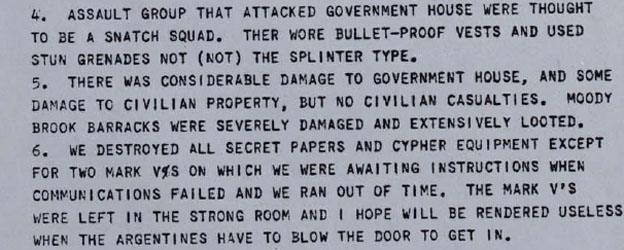

"We destroyed all secret papers and cypher equipment except for two Mark Vs on which we were awaiting instructions when communications failed and we ran out of time. The Mark Vs were left in the strong room and I hope will be rendered useless when the Argentines have to blow the door to get in".

Excerpt from governor's account of final hours at Government House

In the meantime, Britain's ambassador in Buenos Aires, Anthony Williams, had been taking his own "precautionary measures".

A telegram on 1 April noted: "We have already started destruction of all sensitive material prior to 1981 and, more recently, of higher sensitivity.

"We expect to complete this operation inconspicuously within 18 hours or in less time if it becomes appropriate to use incinerator in this smokeless zone."

As Britain assembled a task force to sail for the South Atlantic, it became apparent there were not enough ships. The main requirement was for a passenger liner to carry 1,700 men.

With the Queen's approval, a Royal Prerogative was invoked to requisition a P&O liner, the Canberra, and a freighter, the Norsea, which would carry vehicles and equipment.

A ministerial memo to the prime minister of the time, Margaret Thatcher, had read: "Without these ships, the Chiefs of Staff assessment is that the military capability of the force would be severely degraded, given the likely threat."

Dr Gregory Fremont-Barnes, a lecturer in war studies at Sandhurst, suggests Britain's grand plan was rather "ad hoc". "There was no contingency for retaking the Falklands," he says.

"The papers in the National Archives show the government was caught somewhat wrong-footed. Nonetheless, once the news of the invasion comes through, they operated extremely quickly and the Task Force left on 9 April, a week after the invasion."

On the diplomatic front, Mrs Thatcher received a welcome offer of assistance from President Francois Mitterrand of France on 3 April.

He telephoned her to say: "If there's anything we can do to help, we should like to." But a few weeks later, as the Falklands War entered a critical phase, relations between London and Paris had soured.

The government files reveal intense diplomatic efforts by Britain to prevent the sale of French Exocet missiles to Peru.

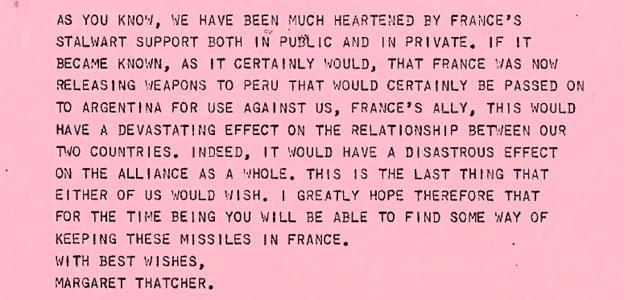

Extract from Mrs Thatcher's telegram appealing to President Mitterrand to delay selling missiles to Peru

In a confidential telegram to President Mitterrand, dated 30 May, Margaret Thatcher said there was dismay in London at the prospect of French missiles ending up in Argentina.

"I must ask you with all the emphasis and urgency at my command to find a means of delaying the delivery of these missiles from France for at least a further month. Naturally we would prefer them not to be supplied at all but the next few weeks are going to be particularly crucial."

Mrs Thatcher wrote that one Peruvian ship had been sent away from France empty, but another ship was on its way to France to take delivery of weapons - Peru was protesting to France about a breach of contract.

Contained in Mrs Thatcher's message to President Mitterrand was an implicit warning: "If it became known, as it certainly would, that France was now releasing weapons to Peru that would certainly be passed on to Argentina for use against us, France's ally, this would have a devastating effect on the relationship between our two countries."

There were no such difficulties between Britain and the United States. A telegram from the British embassy in Washington, dated 3 May, shows that the US Defence Secretary, Caspar Weinberger, had expressed "eagerness to give us (Britain) maximum support". The US even offered the use of an aircraft carrier, the Eisenhower.

However, as the war neared its climax, the Reagan administration in Washington was trying to promote the idea of a joint US- Brazilian peacekeeping force to take over the Falklands.

On 31 May 1982, President Ronald Reagan made a late night telephone call to Mrs Thatcher, urging Britain to talk before the Argentines were forced to withdraw.

According to the notes recorded by John Coles, the prime minister's private secretary, Mr Reagan's view and that of the president of Brazil was that "the best chance for peace was before complete Argentine humiliation".

Mr Reagan apparently said if the UK retained sole military occupancy, the UK might face another Argentine invasion in the future.

However, Mrs Thatcher was in no mood to compromise. "The prime minister emphasised that the UK could not contemplate a ceasefire without Argentinian withdrawal," wrote her private secretary

"The prime minister stressed that Britain had not lost precious lives in battle and sent an enormous task force to hand over the Queen's islands immediately to a contact group."

The PM said she understood the president's fears but as Britain had had to go into the islands alone, with no outside help, she could not now let the invader gain from his aggression, he added.

"She was sure that the president would act in the same way if Alaska had been similarly threatened."

Mrs Thatcher visited British troops on the Falkland Islands in January 1983

The war lasted just over 10 weeks, but the diary of Britain's 3 Commando Brigade paints a bleak picture of conditions in the Falklands as 15,000 Argentine forces surrendered on 14 June.

The Argentines had been dug in for weeks and many were suffering from malnutrition and disease. This created a problem for the victorious British troops as they entered Stanley.

"Near riot as a result of too many POWs moving down from the airfield", was a comment written in the Brigade diary.

The weather was deteriorating. Helicopters could not fly. British forces were short of artillery rounds, and an end to hostilities was not immediately confirmed from Buenos Aires.

"The momentum of the British attack had largely run out of steam in terms of its logistics, not in terms of morale or the brilliant leadership of junior commanders, but in terms of supply. I daresay that if the Argentines had put up a stiff resistance in and around Stanley itself, British forces might have found themselves in very great difficulty," says historian Gregory Fremont-Barnes.

However, 3 Commando Brigade's diary catches the mood as it becomes clear the war is over: "Consolidate, re-organise, sort out, and breath a sigh of relief".

All document images courtesy of the National Archives

- Published28 December 2012