Abuse alert system for hospitals

- Published

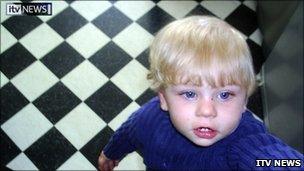

Victoria Climbie died from abuse and neglect in February 2000

An online system to identify children who may be in danger of abuse or neglect is being developed for use in hospitals across England.

The £9m Child Protection Information System will alert doctors and nurses in accident and emergency departments if children are known to be at risk or had urgent treatment at other hospitals.

It will be rolled out from 2015.

Ministers say abuse will be identified earlier. Labour criticised the delay in replacing a database shelved in 2010.

The government has said tragedies that followed missed warnings, such as the cases of Peter Connelly or Victoria Climbie, might be avoided if a common database was shared.

Under the new system, children arriving at a hospital accident and emergency or urgent care centre will be checked on the NHS computer system.

Lisa Harker, NSPCC: "It is people who keep children safe from abuse and neglect, not systems and databases"

That will clarify whether the youngster is on the register for children considered to be at risk, or in council care.

The system is also intended to make it easier for doctors and nurses to see if patients had other emergency admissions elsewhere in the country.

Ministers say by giving professionals the wider picture, abuse can be identified earlier.

Health minister Dan Poulter said the scheme should give professionals "the best tools for the job".

"Up until now, it has been hard for frontline healthcare professionals to know if a child is already listed as being at risk or if children have been repeatedly seen in different emergency departments or urgent care centres with suspicious injuries or complaints, which may indicate abuse," he said.

"Providing instant access to that information means vulnerable and abused children will be identified much more quickly - which will save lives."

Dr Simon Eccles, a consultant in emergency medicine at Homerton Hospital in London who helped set up the scheme, said innocent parents or carers would not come under suspicion.

He told BBC Radio 4's Today Programme: "It's quite straightforward I hope, most of the time, to ascertain whether this is just a child who is beautifully looked after but tends to play rough, or this is a child who is not ever being watched when they play and tend to hurt themselves."

Dr Eccles said that if a member of the clinical team - a nurse, doctor or paediatrician - made a judgement call and believes a child could be at risk, they could each escalate it "up the ladder", which could ultimately result in a visit to the home.

"This database is not trying to solve the entire problem but simply adding another layer of information that previously was hard to get," he added.

Labour claims the coalition undermined child protection when in 2010 it scrapped a much larger child database, introduced by the previous government.

Some charities have also raised concerns.

They say simply sharing information alone will not be enough without better training for medical professionals to spot abuse.

A national flagging system was a key recommendation of the Laming report which came out in 2003, which followed Victoria Climbie's death in 2000.

It was being introduced as part of the Integrated Children's System - a national computer system that flagged up children thought to be at risk from abuse.

But the system was scrapped in 2009 following claims, after the Peter Connelly case, that the system in its early form was too cumbersome and bureaucratic.

Eight-year-old Victoria died from abuse and neglect in 2000 while living with her aunt, Marie-Therese Kouao, and her boyfriend, Carl Manning.

The child was seen by dozens of social workers, nurses, doctors and police officers before she died but all failed to spot and stop the abuse as she was tortured to death.

'Take responsibility'

Peter Connelly, known as Baby P or Baby Peter, died in August 2007 at home in Haringey, north London, after months of abuse which left him with more than 50 injuries.

Details of his case revealed incompetence by social workers, doctors, lawyers and police.

Peter Connelly died with more than 50 injuries

The mother of the 17-month-old boy, her boyfriend and a lodger were later jailed for causing or allowing Peter's death.

Lisa Harker, from the NSPCC, said the charity welcomed the latest plans as a "helpful step", but it was "only part of the solution".

Speaking on BBC Breakfast News, she said it was "people rather than processes" that would make a difference.

She called for better training for doctors and nurses, so that they felt confident to take action if they had suspicions that a child was being abused or neglected, rather than thinking it was enough to "raise the alarm".

"Time and again when we have seen children killed as a result of abuse or neglect, we have seen that professionals have seen it as their responsibility to alert someone else to the problem rather than taking action themselves," she said.

- Published12 June 2012

- Published17 May 2012

- Published10 May 2011

- Published23 January 2012