Businessmen, lawyers and justice

- Published

- comments

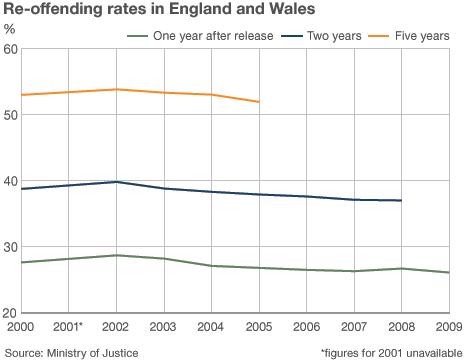

The simple fact that most prisoners come out of jail and reoffend is the government's central justification for dismantling the state-provided probation service in England and Wales. The hard part is putting something else in its place that will work better.

The Justice Secretary Chris Grayling is determined to cut recidivism but he wants to save money at the same time. His answer is, effectively, to privatise probation. All but the highest risk offenders will be managed by non-state providers.

The government talks about private and voluntary sector bodies running the 16 contracts, but few charitable organisations have the capital reserves or expertise to win the tendering process. There will be a role for not-for-profit bodies in front-line delivery of some services, but it looks almost certain that the people in charge will be hardheaded businessmen out to make a return.

The Ministry of Justice is convinced that the profit motive will deliver a cheaper and more efficient service. Critics argue it will lead to confusion, waste and risk.

Companies like Serco, external and G4S, external, which already advertise their willingness to expand into the probation sector, are front-runners for the contracts - a prospect which naturally alarms the 20,000 people employed by the state-run service at the moment.

It is thought that around 14,000 probation officers may lose their state-funded jobs. Many will be re-employed by the private providers but, since one of the key aims of the reform is to save money, a significant number will not.

It is no surprise that the National Association of Probation Officers, the union for the sector, say the government's motives are "purely ideological" and warn that "if this plan proceeds it will be chaotic and will compromise public protection". The association's influence, indeed its very existence, is threatened by the reforms.

What, though, is one to make of the predictions of chaos and public risk? Similar arguments were put forward when the Labour government privatised prisons and introduced payment by results in other public services like the NHS.

Indeed, the concept of "contestability" (market competition) was inserted into the DNA of the National Offender Management Service when it was being created almost a decade ago. The sky did not fall in.

The public risk argument comes down to this: if you have low-medium risk offenders being managed by the private/voluntary sector and high risk offenders by the state sector there will be confusion and error because risk is dynamic.

A survey of probation cases in London has suggested that 24% see a change to their risk status while under supervision. Most, of course, see their assessment go down. But some may suddenly be identified as a much greater risk than originally thought.

Chris Grayling: "I want to capture the skills that exist across the public, private and voluntary sectors."

The man jailed for reckless driving, a low risk at the outset, may emerge as someone who presents serious risk of domestic violence. How easy will it be for that person to be moved from the non-state provided service back into state supervision?

Here lies the conundrum. The government insists that the new streamlined state-run probation service must not be "constantly looking over the shoulder" of the contract providers. Equally, they say the state-run service must have oversight of all cases. Where is the line drawn? Get it wrong, and confusion and risk increase.

The Ministry of Justice stresses that a lot of the detail is still to be worked out; many of the challenges will be dealt with in the construction of the contracts. But, as ever, the devil will be in the detail.

Putting together payment-by-results contracts often proves much more complex than originally planned. For example, an operation where Serco and the existing state-run London Probation Trust jointly provide Community Payback services for the MoJ took around two years to procure.

One big headache is defining the "result" for which payment will be made. In the context of probation, how much reward, if any, should a contractor get if an offender with a history of violent crime commits no offences of violence while supervised, but steals a chocolate bar from Tesco's?

There is also a concern that private providers might maximise profits by focusing on the less challenging cases. Offenders with complex needs may require high levels of investment which don't make business sense. The contract is key in addressing such questions.

So the most important people in deciding whether these proposals work will not be politicians. Nor will they be businessmen, probation officers or voluntary sector mentors. Success or failure will be in the hands of contract lawyers.