Jimmy Savile scandal: What legal redress for abuse victims?

- Published

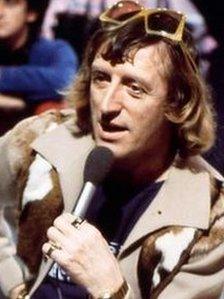

Sexual abuse allegations against Jimmy Savile emerged after his death

The scale of Jimmy Savile's abuse is now known and his many victims will be denied the chance to see him prosecuted for his crimes.

So, what redress do they have? They can bring civil claims for damages for the abuse they suffered, but it will not be straightforward.

These claims can be brought against Jimmy Savile's estate, and against the organisations such as hospitals, children's homes and the BBC, on whose premises and with whom he was associated when the abuse took place.

But will they succeed?

Such cases are classed as personal injury claims. There is normally a three-year period to bring them.

However, in sexual abuse cases if there is good evidence of why the victim did not bring the claim, for instance that the abuse had been buried or the abuser had exercised power over the victims not to come forward, the three-year bar will be dropped.

The civil law governing these claims is rapidly changing, and that change is being driven by cases of historic sexual abuse and a growing awareness of the psychology of abusers and victims.

Negligence claim

There are two ways in which to bring a claim against an organisation. One is complicated, the other is far more straightforward.

A claim can be brought in negligence.

This is complicated. It requires the claimant to establish that they were owed a duty of care which was breached.

It will require evidence of what the organisation knew about the risk posed by Savile, what complaints it received and what protective measures it put into operation to guard against that risk.

The preferred option is to sue the organisation on the basis that they were vicariously liable for the acts of the abuser.

Vicarious liability is almost a piece of social policy. It establishes that when a civil wrong is done to an individual, someone has to pay.

That person has traditionally been the employer who could defend an action if the person committing the wrong was not an employee.

The BBC's Clive Coleman: "This is a real acceptance that the CPS and police absolutely failed."

However, this is where the law is changing. In a major decision at the end of last year the Supreme Court broadened the limits of vicarious liability.

Now an organisation can be sued if the abuser is in a relationship with it that is akin to employment.

So, the fact that Jimmy Savile was not employed as a member of staff at the various organisations where the abuse took place, will not now provide a complete defence to those organisations.

However, there are real problems faced by victims.

In many cases the abuse was not long term and may have happened on a single occasion or a few times.

It is always more difficult to establish the abuse in those circumstances. The large number of victims and the similarity of the way in which the abuse occurred will help here.

More significantly, Savile targeted the vulnerable.

In the case of children who came from dysfunctional backgrounds, or who had previously suffered abuse, the court has a complex task.

With the abuser dead, it will require good quality psychiatric evidence that the psychological harm suffered by the victim was as a direct result of Savile's abuse of them.

Unscrambling psychological evidence which ties harm to specific abuse lies at the heart of many civil claims for damages for historic sexual abuse.

One chapter for the victims has closed, but bringing a civil claim represents a difficult and potentially painful new one.