What is life like for Helmand blast survivors?

- Published

In July 2009 the UK Army suffered the worst attack of the Afghanistan campaign on a foot patrol, when five men from the same platoon were killed by bombs and many more were injured. For those who survived there have been lasting effects.

Posted to Helmand, the men of 9 Platoon, C Company, 2nd Battalion The Rifles, were sent to the town of Sangin and given the job of bringing security to the alleyways around the Wishtan bazaar.

For the first month things were relatively quiet, but as their patrols continued the number of bombs they found began to increase.

Early on the morning of 10 July, as they left a disused compound, a device planted by the Taliban exploded. One of the soldiers was killed outright and six others were injured.

A reserve force scrambled to help their injured colleagues, but as the walking wounded set off for base they triggered a second "daisy chain" of connected devices. A further three soldiers were killed outright, with a fourth dying later at Camp Bastion.

Symbolically, the attack took the number of soldiers killed in Afghanistan above the total lost in Iraq. , external

For the survivors the tour continued, with the threat of further attacks. For many of those involved the impact is still felt, even after their return to the UK.

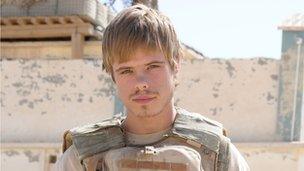

Rifleman Matthew Ramdeen, 23: Not injured in second blast

"You can take yourself back there very quickly, but it's something you don't want to do. It's a constant battle to forget it," says Matthew Ramdeen, who was very close to the second blast.

Matthew thought he had escaped unscathed, but in the summer of 2011 - more than a year after he left the Army - symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) appeared unexpectedly.

Matthew Ramdeen returned to the UK "in one piece", but unexpectedly suffered PTSD

"It was difficult to adjust to civilian life as it was before. You're walking down the street, you're thinking am I going to set off an IED [improvised explosive device] with every step I take?"

His mother, Jo, says he was "paranoid" and would check that they were not being followed and was unable to deal with sudden noises.

"He was fine as in he was back in one piece, he wasn't missing a limb," she says.

But, as Matthew became increasingly aggressive towards her, and his brother, Jo insisted that he seek help. A period on anti-anxiety medication followed and he was offered counselling through Combat Stress, which provides support to veterans.

Matthew is now well and is studying engineering at college, with the aim of becoming an RAF pilot.

"The future is bright and I'm definitely looking forward to it - 100%," he says.

Rifleman Kevin Holt, 24: Not injured in first blast

For the other members of 9 Platoon, Kevin Holt is a hero.

Out on patrol, he ran back to help those caught up in the first blast. He saw his close friend Rifleman James Backhouse killed, but used his metal detector to check for further explosives and clear a path to safety.

For his actions he received a Mention in Despatches - a bravery award for those involved in active operations against the enemy.

But, like many other survivors, he cannot escape the memories of what happened.

Kevin Holt takes comfort from speaking to friends about those killed

"I had mood swings, anger problems," says Kevin, who lives near Doncaster. "At one stage I smashed up my room... I don't even know why. I still have dreams, I still get flashbacks. To be honest with you I haven't really been able to sleep."

Diagnosed with PTSD, for which he is receiving treatment, Kevin left the Army in January 2011 and has struggled to return to civilian life.

"I could go for days without talking to anybody, or just seeing anybody. I get into a 'distant' mood... I just want to be alone. At the minute I'm just taking things day to day. I've not really got any plans," he says.

But although things are difficult, he dreams of starting a new life - possibly in the US.

And he takes comfort from talking to friends from his platoon about those killed.

"The lads that were lost over there, they always come up in conversations. It's just all the good memories," he says.

Rifleman Allan Arnold, 20: Back at base

Although he was not on patrol on the day of the attack, Allan Arnold saw the dead and injured members of his platoon as they were brought back to base. His friend Rifleman William Aldridge was among those killed.

"He informed me his closest friend had died. He was crying. There was nothing that I could do to make it easier for him, I couldn't cuddle him, I could just listen," says his mother, Nickie Smith.

After returning from Helmand Allan Arnold remained in the Army

Like other members of the platoon, he was monitored by senior officers and given the chance to talk through what had happened.

But back in the UK Allan, who joined the Army at 17 despite attention deficit disorder and severe dyslexia, suffered nightmares and turned to drink.

During Army leave in May 2011 he left his sister Abbie's house in Cirencester early one morning and was later found hanged in a copse. He was 20.

"Allan took his own life because he felt that it was too hard to carry on any more," says Nickie. "The nightmares, the flashbacks, the memories, the loss - it was too much in the end for him to cope with. I suppose he saw it as the only way to get peace."

For Abbie, dealing with his death remains painful. "There'll be a song on the radio that will remind me of him... and you get the gut-wrenching feeling in your stomach like you want to be sick because you're never going to see him again."

The town of Sangin was for a time the most dangerous posting for British soldiers in Helmand

Lieutenant Alex Horsfall, 29: Seriously injured in first blast

"It's a date that you remember more than your birthday," says platoon leader Lieutenant Alex Horsfall of the attack.

Severely injured in the first blast, Lt Horsfall was put onto a quad bike trailer by his men - who had also come under fire from several directions - and rushed back to base for treatment.

He had lost part of his lower left leg and part of his left hand in the attack and was flown to Selly Oak Hospital in Birmingham for specialist care. He spent three months there, followed by another two years in and out of Headley Court rehabilitation centre.

Yet Lt Horsfall, who has no memory of what happened after the blast, considers himself lucky.

"I had several riflemen looking after me... they did a bloody good job and it is thanks to them that I'm still here," he says.

The Old Etonian left the Army in January 2012, but still works for the Ministry of Defence and does not appear to be suffering mentally.

Now living in central London, he continues to feel responsible for those in his platoon and stresses the importance of talking about what happened.

"There have definitely been a few cases of things like post-traumatic stress and so there are definitely issues," he says ahead of a planned 9 Platoon reunion he has organised.

"Getting everyone together is… quite a good soothing way to sort of deal with things."

Rifleman Peter Sherlock, 24: Back at base

The death of his close friend Rifleman Daniel Simpson in the second blast affected Peter Sherlock deeply.

Having suffered heatstroke the previous day Peter had been kept back at base, but he saw his injured friends brought in.

He left the Army in 2011 to escape the constant reminders of the attack and admits to drinking heavily - in an attempt to forget.

"If I go out when I am down, like really down, then I come back in a right state. I won't be able to walk or talk properly," he says.

Like many of the survivors, Peter started having nightmares after the attack - but he considers himself fortunate.

"You wake up with quite a jump, quite a fright... so sleeping can be pretty rough. But I feel I'm sort of lucky because it happens when I'm asleep... whereas for some of the lads I know they get it when they're awake."

Now living in Southampton, Peter has cut the amount he drinks and wants to be a good parent to his two-year-old daughter, Hope Liberty, despite being separated from her mother.

"I like wondering what she's up to, what she's doing, how she's doing, how much taller she is, what she's into. I'd love to teach her how to sail. That would be a dream," he says.

Life After War: Haunted by Helmand is shown on BBC Three at 21:00 GMT on Wednesday, 23 January.