UK suicide rate rises 'significantly' in 2011

- Published

Men aged between 30 and 44 were most likely to take their own life in 2011

The number of people taking their own life in the UK rose "significantly" in 2011, latest figures from the Office for National Statistics have shown.

Some 6,045 people killed themselves in 2011, an increase of 437 since 2010.

The highest suicide rate was among men aged between 30 and 44. About 23 men per 100,000 took their own lives.

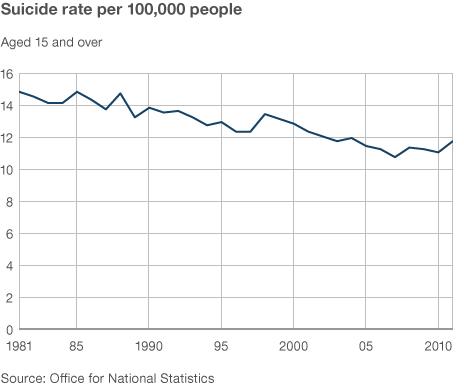

On average, across both sexes, 11.8 people per 100,000 population killed themselves in 2011, up from 11.1 people the previous year.

The ONS data revealed there were 4,552 suicides by men in 2011, more than three times the number by women and the highest rate since 2002.

The suicide rate among middle-aged men aged 45 to 59 was also high, increasing from 21.7 deaths in 2006 to 22.2 deaths per 100,000 people in 2011.

The figures come after the government's pledge last year to put a further £1.5m towards research into suicide prevention among high-risk groups.

Ministers also announced a new suicide prevention strategy aimed at cutting suicide rates and supporting families affected by suicide.

Male suicide rates increased in the 1980s, with the average rate among all age groups peaking at 21.9 deaths per 100,000 population in 1988.

Fewer men killed themselves between 1988 and 2010, though the average rate rose in 1998 and 1999.

After more than a decade of falling suicide rates in males, the rate increased significantly between 2010 and 2011, from 17 to 18.2 deaths per 100,000 population.

In Wales, the suicide rate has increased by about 30% in two years. Out of 100,000 men, 22.5 killed themselves in 2011 compared to 16.2 in England and 13.2 in London.

Suicides among women in 2011 stood at 1,493, with the average number of deaths across all female age groups falling over the past 31 years.

Among women, those aged between 45 and 59 were the most likely to take their own life, at a rate of 7.3 per 100,000. Suicides rates have been consistently lower in females than in males over the past three decades.

When the ONS began keeping records of deaths by suicide in 1981, some 4,129 men and 2,466 women took their own lives.

Additional guidance was published in 2011 in order to improve the classification of narrative verdicts at inquests in England and Wales.

Narrative verdicts, which are long-form, factual records of the circumstance in which a death occurs, can be used instead of short-form verdicts, including suicide.

Researchers had raised concerns that previous classification rules forced the ONS to record probable suicides as accidents, rather than allowing for the classification of intentional self-harm.

The ONS said changes to the guidance may have led to an increased number of narrative verdicts coded as intentional self-harm in 2011, and therefore could have resulted in an increase in the suicide rate.

The University of Reading's Professor Shirley Reynolds, director of the Charlie Waller Institute of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatment, said: "The rise in suicide of men aged 30 to 45 is deeply worrying. Suicide may be linked to financial and work-related problems, as well as loss of employment and limited emotional, practical and social support from other people."

She added it was "essential that we work to reduce the stigma associated with mental health problems so everyone is able to ask for the help they need".

'Perfect storm'

Samaritans trustee Stephen Platt said: "The most important issue raised by these figures is the urgent need to tackle the many difficulties faced by men in their middle years."

He said disadvantaged men in mid-life were facing a "perfect storm" of challenges, including unemployment and social inclusion.

"It is high time that national suicide prevention strategies address suicide as a health and social inequality at both national and local levels," he said.

Care services minister Norman Lamb said the rise in suicide numbers was a "very real concern" and pledged to tackle the problem "head on".

He said the government's refreshed suicide prevention strategy targeted those most at risk by "providing the right interventions at the right time", but added it needed to "make sure information about treatment and support is available to those who need them, including those who are suffering from bereavement following a suicide".

- Published20 September 2012

- Published10 September 2012

- Published7 October 2011