Kiwis on drugs: A blueprint for the future?

- Published

- comments

Evidence from a New Zealand drugs operation, 2006

Want to know what the future for global drug control looks like?

This week New Zealand publishes its Psychoactive Substances Bill, legislation which some believe will transform the international debate on drugs policy when it comes into force in August.

The new law is a response to the problem of "legal highs", but is being seized upon by reformers because it crosses a Rubicon - designing a legislative framework built upon regulation rather than prohibition.

As in Britain, the New Zealand government had attempted to control the influx of new psychoactive substances by imposing emergency restrictions under existing misuse of drugs legislation.

Unlike Britain, they have concluded that a "long-term and more effective solution" is to license the importation, manufacture and sale of all new psychoactive products.

In the same way as pharmaceutical companies must apply for a licence to sell a drug after extensive testing, so suppliers of legal highs will be able to market products in New Zealand if they can demonstrate they present a low risk of harm.

Rather than trying to ban every new drug that turns up, the legislation shifts responsibility to the manufacturer and the retailer.

Just as a bottle of aspirin can only be sold in certain outlets with all the warnings of the risks on the label, so recreational drugs will be available over the counter in New Zealand later this year.

There will be restrictions on sales to vulnerable consumers, particularly young people, and breaches of the rules could see manufacturers fined up to $500,000 (£275,000) or jailed for two years.

The legal highs dilemma reminds me of the panic that preceded the introduction of the Misuse of Drugs Act in the UK in 1971.

The home secretary at the time, Jim Callaghan, told Parliament how Britain faced a "pharmaceutical revolution" which presented such dangers that if the country was "supine in the face of them" it would quickly lead to "grave dangers to the whole structure of our society".

Jim Callaghan argued drug abuse should be tackled through state prohibition

"Stimulants, depressants, tranquillisers, hallucinogens have all been developed during the last 10 years, and our society has not yet come to terms with the circumstances in which they should properly be used or in which they are regarded as being socially an evil," he explained.

Callaghan concluded that the answer was state prohibition - the criminal justice system would be the main tool to fight drug abuse. Those who argued that Britain should retain its traditional harm-reduction model were drowned out.

The New Zealand legislation comes at a key moment in the debate about global drugs policy, returning us to that moment in the late 60s when Britain and others took the fork in the road marked "prohibition".

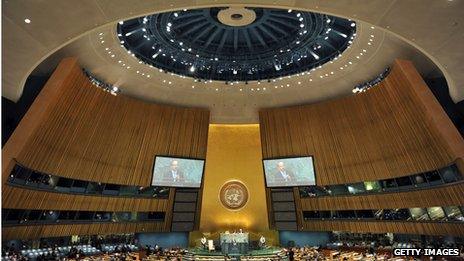

This year has been designated by the United Nations as the start of an "intense preparatory process", before the General Assembly holds a special session in 2016 to "review the current policies and strategies to confront the global drug problem".

There is very little intensity or preparation in the UK, where the prime minister recently reiterated his opposition to even questioning the prohibition model.

When the Home Affairs select committee recommended a royal commission to consider alternatives in December, David Cameron instantly dismissed the idea arguing "we have a policy which is working in Britain".

United Nations General Assembly

You may recall, however, that in an interview with me, the Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg broke coalition ranks to demand a fundamental review of Britain's drug laws as part of Britain's preparations for the UN General Assembly meeting in three years time.

His aides told me Mr Clegg believes the UK needs to have at least considered the issues and how they might shape the EU's negotiating stance ahead of a UN session that has the capacity to rewrite the international drugs conventions.

What principles should guide Britain, Europe and the UN in considering a possible new approach to the problem of dangerous drugs?

The former head of the UK government's Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), Professor David Nutt has sent me his thoughts.

Prof Nutt, of course, was sacked by the last Labour government after publicly questioning the wisdom of the prohibition-based policy, but has subsequently been involved in helping the New Zealand government design their Psychoactive Substances Bill.

He has a wish list of principles for laws on drugs:

They should cover all drugs including alcohol and tobacco, and any new/future synthetics

Health should be the defining principle

Interventions should be proportionate to harm (and be as evidence-based as possible)

Human rights should be respected

They should minimise unexpected consequences

They should be globally balanced (ie take account of effects in all countries)

Local/national autonomy should be allowed as far as possible.

This is an interesting starting point for a debate ahead of the global drugs summit (UNGASS 2016 in the jargon) and I would be interested in readers' reaction to it.

How Britain and the European Union line up at the special session will probably be less important than the stance of the US, who were the architects of the current key international drug conventions.

Just before Christmas, President Obama was asked for his response to the decision of two US states, Washington and Colorado, to legalise the recreational use of marijuana. "It would not make sense for us to see a top priority as going after recreational users in states that have determined that it's legal," he said. "We've got bigger fish to fry."

While President Obama has re-stated his personal opposition to the legalisation of marijuana and maintains the official US government position, some have noted that he said he does not "at this point" support a change in direction.

With Uruguay announcing its intention to breach UN conventions and legalise marijuana under state control, Obama's stance on Colorado and Washington makes it very hard for the US to justify sanctions against such countries and provides ammunition for those who argue global drugs policy is no longer sustainable.

Could New Zealand's legislation to control legal highs be a blueprint for the future?