Iraq: The spies who fooled the world

- Published

The lies of two Iraqi spies were central to the claim - at the heart of the UK and US decision to go to war in Iraq - that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. But even before the fighting started, intelligence from highly-placed sources was available suggesting he did not, Panorama has learned.

Six months before the invasion, the then Prime Minister Tony Blair warned the country about the threat posed by Saddam Hussein's weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

"The programme is not shut down," he said. "It is up and running now." Mr Blair used the intelligence on WMD to justify the war.

That same day, 24 September 2002, the government published its controversial dossier on the former Iraqi leader's WMD.

The BBC has learned that two key pieces of intelligence, which could have prevented the Iraq war, were either dismissed or used selectively

Designed for public consumption, it had a personal foreword by Mr Blair, who assured readers Saddam Hussein had continued to produce WMD "beyond doubt".

But, while it was never mentioned in the dossier, there was doubt. The original intelligence from MI6 and other agencies, on which the dossier was based, was clearly qualified.

The intelligence was, as the Joint Intelligence Committee noted in its original assessments, "sporadic and patchy" and "remains limited".

The exclusion of these qualifications gave the dossier a certainty that was never warranted.

Intelligence failure

Much of the key intelligence used by Downing Street and the White House was based on fabrication, wishful thinking and lies.

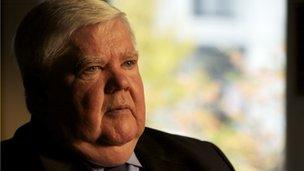

Lord Butler says he was unaware of some intelligence that Saddam Hussein did not have WMD

As Gen Sir Mike Jackson, then head of the British Army, says, "what appeared to be gold in terms of intelligence turned out to be fool's gold, because it looked like gold, but it wasn't".

There was other intelligence, but it was less alarming.

Lord Butler, who after the war, conducted the first government inquiry into WMD intelligence, says Mr Blair and the intelligence community "misled themselves".

Lord Butler and Sir Mike agree Mr Blair did not lie, because they say he genuinely believed Saddam Hussein had WMD.

The most notorious spy who fooled the world was the Iraqi defector, Rafid Ahmed Alwan al-Janabi.

His fabrications and lies were a crucial part of the intelligence used to justify one of the most divisive wars in recent history. And they contributed to one of the biggest intelligence failures in living memory.

He became known as Curveball, the codename given to him by US intelligence that turned out to be all too appropriate.

Mr Janabi arrived as an Iraqi asylum seeker at a German refugee centre in 1999 and said he was a chemical engineer, thus attracting the attention of the German intelligence service, the BND.

He told them he had seen mobile biological laboratories mounted on trucks to evade detection.

The Germans had doubts about Mr Janabi which they shared with the Americans and the British.

MI6 had doubts too, which they expressed in a secret cable to the CIA: "Elements of [his] behaviour strike us as typical of individuals we would normally assess as fabricators [but we are] inclined to believe that a significant part of [Curveball's] reporting is true."

The British decided to stick with Curveball, as did the Americans. He later admitted being a fabricator and liar.

There appeared to be corroborative intelligence from another spy who fooled the world.

He was an Iraqi former intelligence officer, called Maj Muhammad Harith, who said it had been his idea to develop mobile biological laboratories and claimed he had ordered seven Renault trucks to put them on.

He made his way to Jordan and then talked to the Americans.

Muhammad Harith apparently made up his story because he wanted a new home. His intelligence was dismissed as fabrication 10 months before the war.

MI6 also thought they had further corroboration of Curveball's story, when a trusted source - codenamed Red River - revealed he had been in touch with a secondary source who said he had seen fermenters on trucks. But he never claimed the fermenters had anything to do with biological agents.

After the war, MI6 decided that Red River was unreliable as a source.

Handmade suit

But not all the intelligence was wrong. Information from two highly-placed sources close to Saddam Hussein was correct.

Both said Iraq did not have any active WMD.

The CIA's source was Iraq's foreign minister, Naji Sabri.

Former CIA man Bill Murray - then head of the agency's station in Paris - dealt with him via an intermediary, an Arab journalist, to whom he gave $200,000 (£132,000) in cash as a down payment.

He said Naji Sabri "looked like a person of real interest - someone who we really should be talking to".

Murray put together a list of questions to put to the minister, with WMD at the top.

The intermediary met Naji Sabri in New York in September 2002 when he was about to address the UN - six months before the start of the war and just a week before the British dossier was published.

The intermediary bought the minister a handmade suit which the minister wore at the UN, a sign Mr Murray took to mean that Naji Sabri was on board.

Mr Murray says the upshot was intelligence that Saddam Hussein "had some chemical weapons left over from the early 90s, [and] had taken the stocks and given them to various tribes that were loyal to him. [He] had intentions to have weapons of mass destruction - chemical, biological and nuclear - but at that point in time he virtually had nothing".

The CIA insists the intelligence report from the "source" indicated the former Iraqi president did have WMD programmes because, the agency says, it mentioned that, "Iraq was currently producing and stockpiling chemical weapons" and "as a last resort had mobile launchers armed with chemical weapons".

Mr Murray disputes this account.

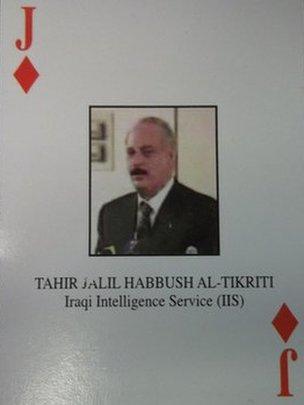

The second highly-placed source was Iraq's head of intelligence, Tahir Jalil Habbush Al-Tikriti - the jack of diamonds in America's "most wanted" deck of cards which rated members of Saddam Hussein's government.

A senior MI6 officer met him in Jordan in January 2003 - two months before the war.

Bill Murray says the "best intelligence" was not used

It was thought Habbush wanted to negotiate a deal that would stop the imminent invasion. He also said Saddam Hussein had no active WMD.

Surprisingly, Lord Butler - who says Britons have "every right" to feel misled by their prime minister - only became aware of the information from Habbush after his report was published.

"I can't explain that," says Lord Butler.

"This was something which I think our review did miss. But when we asked about it, we were told that it wasn't a very significant fact, because SIS [MI6] discounted it as something designed by Saddam to mislead."

Lord Butler says he also knew nothing about the intelligence from Naji Sabri.

Ex-CIA man Bill Murray was not happy with the way the intelligence from these two highly-placed sources had been used.

"I thought we'd produced probably the best intelligence that anybody produced in the pre-war period, all of which came out - in the long run - to be accurate. The information was discarded and not used."

Panorama: The Spies Who Fooled the World, BBC One, Monday 18 March at 22:35 GMT and then available in the UK on the BBC iPlayer.