UK child well-being: Problems and progress

- Published

I remember the soul-searching well.

The UK had been labelled the worst country in the west for a child to grow up in. Politicians, church leaders and charities complained that a generation was being failed.

The evidence for this gloomy prognosis was a Unicef report on child well-being in rich countries, external.

The UK emerged an ignominious 21st out of 21 developed nations and Time magazine ran a front cover suggesting British children were "unhappy, unloved and out of control".

Now we have the much anticipated update and similar voices are out in force to make the same point.

Education Minister David Laws says the report "lays bare Labour's failures on education and child well-being".

Save the Children warns about young people being left "without the investment that gives them a fair chance in life" and the Children's Society says the report "shows we still have a very long way to go".

Not perfect

Reading these responses one might imagine that Unicef had identified the same desperate and dismal findings that so shocked Britain when they reported in 2007.

But, actually, I think this document chronicles some really important progress.

Not everything is perfect, there are still huge challenges ahead, but there is much to welcome in the new report.

And to ignore the improvements is to risk maintaining the discussion of youth in the UK as one of problems rather than progress.

Look at the stats: Our young people are drinking less, smoking less, taking fewer drugs.

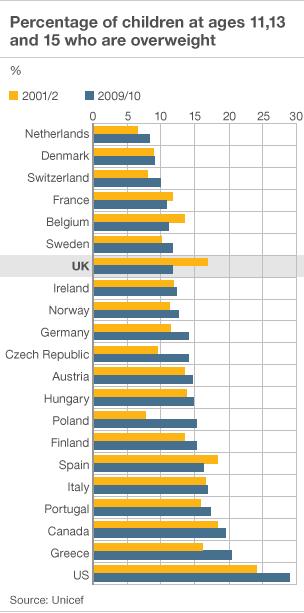

While half the countries in the report have seen their children getting fatter, in the UK fewer youngsters are overweight than in the previous report.

Teenagers are involved in less fighting and when you ask them about their own sense of life satisfaction, British kids report one of the biggest improvements in the western world.

British trait

Much is made of the report's findings on "education well-being".

It is true that the proportion of 15-19-year-olds who remain in education sees the UK at the bottom of the league table.

But this is a statistic likely to be transformed by changes in England which make education compulsory up to 17 this year and up to 18 in 2015. The figures for "Neets" should also be improved by the measure.

Actually, educational achievement by 15-year-olds in the UK compares more favourably with other developed countries than many might imagine.

They out-perform the Danes, the Irish, the French, the Americans - even the Swedes. We come 11th out of 29 rich nations - not good enough, perhaps, but hardly desperate.

The reasons for the gloomy response to the report are largely political.

The coalition government is quick to point out that report only compares data up to 2010 and is therefore a verdict on the previous administration. Small wonder they focus on the bad stuff.

Charities concerned with child welfare are also reluctant to sound too positive - not least because of anxieties over how austerity will impact on young people's lives in the coming years.

And it is quite right to point out that 16th in the overall well-being table is still not good enough. Why are our children apparently faring less well than those in the Czech Republic or Slovenia?

It is a British trait to obsess about the bad without giving proper recognition to the good.

Of course we shouldn't hang out the bunting and cry "job done!" but there is surely value in considering where and how we have achieved success.