Margaret Thatcher: A tribute to conviction politics

- Published

It was a funeral conducted beneath a neutral grey sky, but many of those who lined the streets had come because Margaret Thatcher personified the very opposite of what the weather had to offer.

In the doorway of a sports shop near St Paul's Cathedral, I met 62-year-old John, who had put on a union jack shirt before heading to the funeral from Suffolk.

"I am here to represent the silent majority," he said. "Mrs Thatcher always stood by her views. These days there's no difference between the three current party leaders."

"The current political scene is so bland," agreed his friend Tim, a former bank manager from Essex who yearned for the passion which defined the political scene during the Thatcher years.

Asking why people had made the journey, again and again it came back to this same idea. Mrs Thatcher embodied something they felt had also died - conviction politics. They grieved for a time when leadership was defined by a single-minded, straightforward sense of purpose and direction.

"She was a strong leader, in contrast to what we have today," Julia told me. A solicitor on maternity leave, she had brought five-month-old Freddy to witness a moment in history. "I wouldn't vote Conservative today, but I would have voted for Margaret Thatcher."

With the passing of time, the nuance of events tends to fade. Like sunshine stealing back the colours from a poster in a window, history often turns our memories into black and white. So it is with Margaret Thatcher.

"Which side are you on?" sang Billy Bragg in 1987, as Mrs T asked if people were "one of us". It was a time of social and political tribalism - bosses v workers, left v right, Labour v Tory. Apparently stripped of the discomfort of compromise, politics is remembered as simpler and better.

Having a cup of tea before the funeral, I bumped into David Cameron's advisor Steve Hilton.

"She was always a fighter," he told me. Reflecting on the recent "ding-dong" over her memory, he said: "She would see this controversy as evidence that she made great things happen, because you never make great things happen without shaking things up."

I detected a disappointment that coalition politics meant a Borgen-style search for consensus. As we chatted, we were joined by the Conservative Culture Minister Ed Vaizey. "She was radical and had clear views," he said, explaining why Baroness Thatcher was such a political heroine. "She questioned everything. She constantly asked why do things have to be this way."

For those few who lined the funeral route to protest at what Margaret Thatcher stood for, there was the same disappointment that contemporary politics is conducted on the middle ground.

One protester, Hillary Jones, said: "So many people internationally and domestically could have done with the help of a strong lady like that, but instead she turned her back on us and she looked after the rich and the powerful. So we're here to turn our backs on her now."

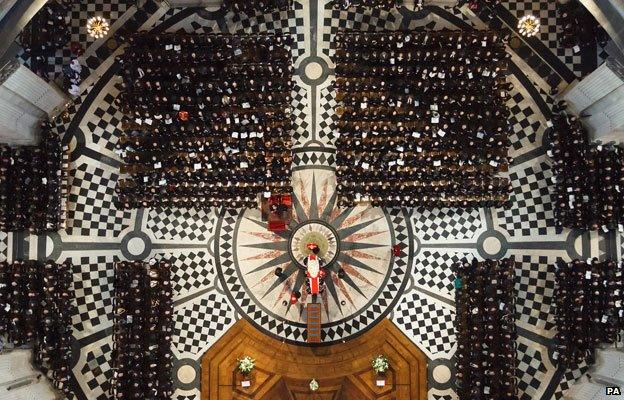

Among the black-suited crowds mustering in the shadow of the great dome of St Paul's, I met a group of young people, most of who were not even born when she left office. They'd come up from Wales to pay their respects.

"We are all Thatcher's children," said David, who now works as a financial trader. "The consensus politics of the 1970s was not working. We needed Thatcherism."

Sam, a 20-year-old history student and Conservative activist from Carmarthenshire, nodded. "She is my inspiration," he told me. His friend Alice, also 20, described Lady Thatcher as a big deal. "She had fantastic suits and hair," she said.

"Thatcher's children": George, David, Sam and Alice

Eon Matthews is a Falklands veteran who served in the navy and was attending as a representative of the South Atlantic Medal Association. "She was a woman who knew how to run a house," he said. "Margaret Thatcher seemed to get things done."

It was a point echoed by others. Steve from Hertfordshire said that at the end of the 1970s, someone had to emerge to take matters in hand. "England was a pretty grey place pre-1979 and it had to change."

He glanced up at the flat grey sky overhead.