The riddle of peacefulness

- Published

- comments

The UK Peace Index, published on Tuesday, attempts to answer a fascinating question: why has our country become "substantially and significantly" more peaceful?

Having set itself this conundrum, however, the UKPI - published by the Institute for Economics and Peace - cannot come up with a convincing answer, not least because the decrease in violence is not confined to Britain. In fact, a similar phenomenon can be seen in almost every developed nation.

The report notes that "there is no commonly accepted explanation by criminologists for the fall in violence in many of the world's regions including the US, Western Europe, Eastern and Central Europe, as well as the UK".

It goes on to admit that "many of the more common theories" refuse to stand up to scrutiny. The global financial crisis has seen many countries suffer severely in economic terms and yet levels of peacefulness have increased. The idea that violent crime goes up when the economy goes down is not backed by the evidence.

Do more police officers mean fewer acts of violence? "The result is seemingly counterintuitive," admits the peace index report. The correlation between policing levels and violent crime in the UK is "very weak", it concludes.

Any specific relationship between police numbers and murder, gun crime or public disorder is "even weaker", the analysis finds. "This suggests that the reductions in police numbers have not played a significant role in either reducing or increasing crime."

The link between violent crime levels and criminal justice policy seems thin. After all, violence has fallen in most developed nations irrespective of their use of prisons, the severity of sentences or the activities of law enforcement officers.

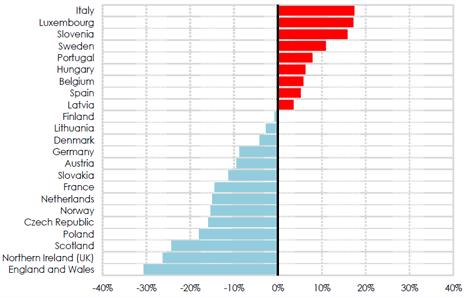

% change in total recorded crime

Source: Institute for Economics and Peace

The analysis searches for correlations between violence levels and other factors. Looking at the list of most and least peaceful local authorities, it is obvious that relatively prosperous rural areas are more peaceful than deprived urban areas.

The 17 most violent authorities in the UK are all London boroughs which contain pockets of extreme poverty, while the most peaceful places tend to be wealthier areas in the south and east of England.

The analysis concludes that "peace is strongly linked to deprivation in income, employment opportunities, health and disability, education and in access to housing and services". However, inequality does not seem to be such a strong correlate with violence.

"The disparity between income levels (the Gini coefficient), while still significant, has a much weaker correlation with peace than poverty'," the report notes.

This goes against a number of research papers which have suggested it is the gap between rich and poor that matters, rather than poverty itself, when it comes to public disorder and violent crime.

The researchers claim that when individuals and families live below a certain level of income and struggle to meet day-to-day needs, this "increases the chance of living in violent communities with anti-social behaviour".

If this is correct, it would suggest that during tough economic times, one might expect to see violence levels rise. But as the report itself points out, this does not appear to be happening during the current downturn.

Perhaps it is too early for the impact to have fed through, but I do wonder whether the analysis is focusing on traditional social and criminal justice theories when the answer to the quite remarkable drop in violence may lie somewhere else entirely.

If one accepts that this phenomenon is affecting developed nations across the planet irrespective of their domestic policies, it seems logical that we are seeing the consequence of a global effect.

Could it be that global communication, particularly the internet, is having a civilising and calming effect on people's behaviour? We live in an age when, for the first time in history, people from all backgrounds can get an understanding of how the rest of the world lives without needing to leave the comfort of their living room.

This mass socialising may be changing attitudes. In the UK there is good evidence that people are becoming more tolerant of difference and less tolerant of violence.

Behaviour that may once have been accepted with a sad shrug now demands a political response. Attitudes towards domestic violence, child abuse and drunken aggression have changed enormously in the past few decades, both at an administrative and social level.

It will be interesting to see, for example, how the international outrage at the rape and sexual abuse of some women in India affects behaviour in the sub-continent. In the UK, scandals around historic acts of violence - notably the Jimmy Savile case - may also reflect what might be called a new morality.

I am often impressed by the way in which school children campaign against discrimination and prejudice. Youngsters are very quick to accuse parents of being sexist or racist or some other -ist following the most innocuous remarks.

The riddle of peacefulness remains a riddle. But there is huge value in trying to understand what is happening - not least for the day when the figures start to move the other way.

Broadland in Norfolk was named the most peaceful local council area

- Published24 April 2013