Abu Qatada case: UK agrees assistance treaty with Jordan

- Published

- comments

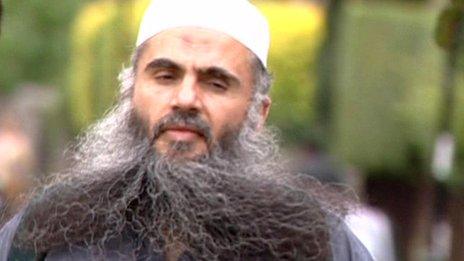

Home Secretary Theresa May warned that the legal process "may well still take many months"

The government has signed a mutual assistance treaty with Jordan to ensure that radical cleric Abu Qatada can be deported, Theresa May has told MPs.

The home secretary said the treaty had guarantees on fair trials within it.

The government is doing "everything it can" to deport Abu Qatada, she said.

The move comes after she failed to get the case referred to the Supreme Court to reverse a ruling that the radical cleric could face an unfair trial if sent to Jordan to face terror charges.

Mrs May is to apply directly to the Supreme Court for permission to challenge that ruling.

The treaty would come into play should the Supreme Court reject the government's request.

The withdrawal of the UK from the European Convention on Human Rights is another option being explored by the prime minister, said Mrs May, who added that it was "sensible" to have "all options on the table".

But cabinet minister and former home secretary Ken Clarke dismissed that idea, saying it is "not the policy of this government".

'Every chance'

Giving a statement to the Commons, Mrs May said the treaty, external would have to be ratified by the UK and Jordan.

She said she believed it would satisfy concerns that Abu Qatada would not receive a fair trial there, and there was now "every chance" of deporting the cleric.

However, Mrs May added that even once the agreement was fully ratified, Abu Qatada would still be able to launch a legal appeal. This could mean it may still be months before he is deported.

Mrs May told the Commons: "I believe these guarantees will provide the courts with the assurance that Qatada will not face evidence that might have been obtained by torture, in a retrial in Jordan."

Shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper said she was willing to work with the government towards Abu Qatada's deportation, but accused Mrs May in the past of "overstating her legal strategy, which has not worked".

On the possibility of the UK temporarily withdrawing from the European Convention on Human Rights, Mrs May said it was her view that the UK needed to "fix that relationship".

BBC political correspondent Vicki Young said any suspension of the UK's membership of the ECHR is almost unprecedented and the Lib Dems are insisting they would block it.

She said: "We're told that the failure to deport Abu Qatada makes David Cameron's blood boil and he's ordered ministers to find a solution.

"The best case scenario for the government is that the Supreme Court agrees to hear the case and rules that Qatada can be deported, but few think that likely."

Mr Clarke, a former home secretary, told BBC Radio 4's World at One programme: "If I was asked my advice on that by any of my colleagues I would say I don't think that's got the faintest thing to do with the case with Abu Qatada.

"It is not the policy of this government to withdraw either for any short period or any lengthy period from the European Convention on Human Rights."

'Denial of justice'

The Special Immigration Appeals Commission (Siac), which adjudicates on national security-related deportations, ruled last year that Abu Qatada should not be removed from the UK because his retrial could be tainted by evidence obtained by torturing the cleric's former co-defendants.

Mrs May had argued she had obtained fresh assurances that would guarantee the fair treatment of the preacher on his return to Amman.

But the Court of Appeal upheld Siac's decision, external last month, saying the lower court had not misinterpreted nor misapplied the law.

Yvette Cooper: Theresa May has "overstated her legal strategy"

Government lawyers had stressed that Jordan had banned torture and the use in trial of statements extracted under duress.

But the Court of Appeal judges said Siac had been entitled to think there was a risk the "impugned statements" would be used in evidence during a retrial and there was "a real risk of a flagrant denial of justice".

The Supreme Court can reconsider Court of Appeal decisions if the justices are convinced there is a "point of law of general public importance, external".

On 17 April 2012, the home secretary told the Commons that, following fresh assurances from Jordan that he would get a fair trial, "we can soon put Qatada on a plane and get him out of our country for good".

Bids for freedom before the European Court of Human Rights and the High Court followed before Abu Qatada's successful appeal to Siac in November.

Abu Qatada was re-arrested and returned to Belmarsh prison in March, following an alleged breach of bail conditions, concerning the use of communications equipment at his home.

Abu Qatada was born in Bethlehem in 1960 and spent his early life in Jordan. He fled to Pakistan in 1989 claiming political persecution and eventually arrived in the UK in 1993. Abu Qatada was part of a wave of Islamists who sought refuge in the UK during the 1980s and 90s, often exiled from the Arab regimes they were trying to overthrow.

Abu Qatada emerged as a key voice in the Islamist movement in London, which advocated strict Islamic government in Muslim countries and armed struggle against despots and foreign invaders. His preachings and ideas won him influence among Islamist groups in Algeria and Egypt during the 1990s. He was tried and found guilty in his absence of terrorism offences in Jordan in 1999.

By 2001 fears were growing about Abu Qatada's hard-line views. He endorsed suicide attacks in a BBC interview and was questioned in connection with a German terror cell. Copies of his sermons were found in the Hamburg flat used by some of the 9/11 attackers and Spanish judge Balthazar Garzon described him as the "spiritual head of the mujahideen in Britain". In December 2001, Abu Qatada disappeared and became one of the UK's most wanted men.

In October 2002 Abu Qatada was arrested and detained without charge. He was released in 2005 and put under strict house arrest, but months later was arrested under immigration rules and moves began to deport him to Jordan to face retrial on the charges he had been convicted of six years earlier. In 2007 he lost his immigration case, but the Court of Appeal later ruled that deportation to a regime which uses torture - ie Jordan - would breach his human rights.

The Court of Appeal ruling was overturned by the Law Lords in early 2009, and the then Home Secretary, Jacqui Smith (L), signed a deportation order. Abu Qatada then appealed to the European Court, which eventually ruled that he could not be deported while the risk of torture remained. In 2012 Home Secretary Theresa May (R) pressed ahead with deportation, but this was blocked amid a row over the appeal deadline.

In November 2012 Abu Qatada was released from prison once more after a UK court backed his appeal on the grounds that witness evidence obtained by torture could be used against him at trial in Jordan. That was a disastrous blow to the Home Office because it meant the only way the deportation could happen would be if Jordan changed its system to ensure torture-tainted evidence could not be used.

Abu Qatada was then returned to prison on 9 March 2013 after an alleged breach of his bail conditions - but this deportation was still blocked. Weeks later, Home Secretary Theresa May announced a new UK-Jordan treaty to improve co-operation in criminal investigations. That treaty included a guarantee of a fair trial free of torture-tainted evidence for anyone sent back to Jordan. Abu Qatada's lawyers announced he would now return to Jordan.

- Published24 April 2013

- Published23 April 2013

- Published10 May 2013

- Published26 June 2014