What can UK learn from Spanish high speed rail?

- Published

Watch David Grossman's Newsnight film in full

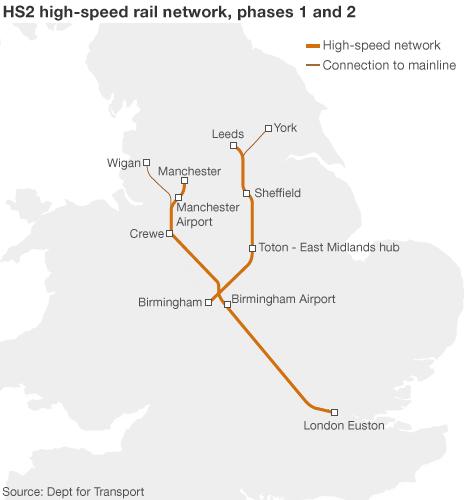

There are many arguments made for the planned new high-speed rail network from London to Birmingham and to Manchester and Leeds, known as HS2. Economic growth and capacity are two of the big ones.

But one you hear politicians routinely reach for whenever the wisdom of the project and its £32.7bn price tag is questioned is that it will bring major economic benefits, particularly to the north of England and the Midlands.

Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg talks about using HS2 to "heal the north-south divide". Prime Minister David Cameron says it will "rebalance the economy away from the South East".

You can see why the politics of this makes sense. And there is, at least at first glance, a logic to the economic argument - if Manchester is suddenly one hour away instead of 2.5 hours it could tempt orders away from the capital and businesses would be able to relocate taking advantage of cheaper costs, spreading wealth and jobs to our northern cities and beyond.

But can we assume that is the direction that the economic benefits will flow?

Close to the centre of Seville, in southern Spain, is a hi-tech success story. Alter Tuv Nord tests and sources components for satellites. It is just the sort of company that the UK government would love to see setting up in the north of England.

Alter Tuv Nord relocated here from the capital Madrid in 1992, the same year that Spain's first high-speed rail line opened.

Towards the end of the 1980s Spain had a similar problem to the UK - wealth and jobs concentrated in one place - for them it was in the rich north.

The government decided to build the Alta Velocidad Espanola (AVE) high-speed rail service linking the capital Madrid with Seville.

The objective was clear. To spread the jobs wealth and development south, away from the overheated capital.

The line opened in April 1992 to coincide with Seville hosting the world's fair, Expo 92.

So has it worked?

The journey to Seville now takes two-and-a-quarter hours, as opposed to the seven hours by train and sometimes 10 by car before high speed rail.

That has undoubtedly been a huge boon to people who already had to make the trip. But, say economists, the Andalusia region in which Seville sits has not benefited as much as you might expect.

"The problem with the south of Spain is that there is a lack of other conditions - for example skills, people, attitudes and diversification of the economy," Gonzalo Sanz-Megallon, Economics professor at Madrid's Universidad San Pablo-CEU tells me.

"Nowadays to promote a region you need innovation, you need education, you need attitudes of people and those things are not promoted or developed in Seville and in the south of Spain."

Professor Sanz-Magallon says that the rail link has contributed little to the southern Spanish economy

John Tomaney is Professor of Urban and Regional Planning at University College London (UCL) and was commissioned by the Commons Public Accounts Committee to write a report on HS2.

"If we look at the evidence from economic analysis and experience from elsewhere round the world" he says, "It's very difficult to prove a link between building high speed rail lines and closing regional inequalities."

Prof Tomaney says there is no firm evidence that high speed rail has been positive for Seville - or indeed other smaller cities. In fact, he says the opposite is the case, and that there is some evidence that high speed rail entrenches the dominance of already rich cities:

"More productive firms in cities like London will be able to serve distant markets in northern cities much more efficiently from their existing base rather than from bases located in the northern cities," he says.

"So, if the time to market is reduced between London and the northern cities, that is going to mainly benefit firms that are already located in London. That seems to be what happens in most of the cases around the world where these railway lines have been introduced."

And if the experience of Seville is any guide for the UK it will take more than just a new train line to get firms to relocate.

Talking to the executives at Alter Tuv Nord you find other more important reasons for the move from Madrid than just the high speed line.

Walter Fisher, the company's corporate development manager, says that their main reason for relocating were the handsome subsidies offered by both the Andalusia government and the European Union.

For a start they were given one of the pavilions from the 1992 Seville Expo on very favourable terms.

"We moved for three reasons," Mr Fisher told me. "The first one was the support that the local and the city council was providing at that time to companies moving. The second was the existence of a very good technical university here in Seville which provides us with the right people... the last one was the existence of good connections with Madrid."

Right next door to the high-tech labs of Alter Tuv Nord are other pavilions left over from the 1992 Expo which have not found new occupants.

Although no-one I met in Spain wanted to go back to the days when it took more than seven hours to travel between Madrid and Seville by train the high speed line has not precipitated the change of fortunes for this impoverished city that some had promised.

The Seville-Madrid line was the first of many built in Spain. The railway operating company Renfe makes a profit, but will never repay the billions it cost to build.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the company's head, Julio Gomez-Pomar, says that the link has been great for the Spanish economy.

There have been a number of protests along the proposed high speed rail route in England

But he also says there are two lessons Spain has learned that the UK should note if it wants high-speed rail to work. Firstly, the government should strangle domestic air travel and force people onto the trains, and secondly long distance rail travel will not work unless connected to a shorter high-speed commuter network of the type that they have now built in Spain.

There are plenty of differences of course between Spain and the UK. One big one is that when they built high speed rail here the journey time savings were huge - far higher than they would be in in the UK which is already pretty well connected.

The Department for Transport says the project will cut Birmingham-London journey times from 1hr 24min to 49min. After the second phase, Manchester-London journeys would take 1hr 8min (down from 2hr 8min), and Birmingham-Leeds 57min (from 2hr).

In 2006, the UK's Labour government's transport review dismissed high speed rail on the basis that the benefits would be too small to justify the cost.

Construction on the London-West Midlands phase is expected to begin around 2017. The onward legs to Manchester and Leeds could start being built in the middle of the next decade, with the line open by 2032-33.

Already there has been controversy about the exact route of the line and its effect on those living near it.

"Their lawns or our jobs" was the slogan of a leaflet put out by supporters of HS2 in the UK. And just in case you did not get the message, there was a toff in a bowler hat to hammer it home - it is posh southern Nimbys selfishly objecting to something that would bring jobs and investment to the north.

It would, of course, be amazing if the government spent £32.7bn on HS2 and it did not bring some - even thousands of jobs to northern cities like Manchester and Leeds.

The question that has not so far been answered is this: If the objective of this huge project is to realign our economic geography or even to "heal the north-south divide" are there better ways of spending the money?

- Published28 January 2013

- Published28 January 2013

- Published6 October 2023