A popular idea still on probation

- Published

The justice secretary must think he is on to a winner. You'll be hard-pressed to find anyone who doesn't think it's a great idea to supervise every offender for a year after they leave prison.

And to do it without costing the tax-payer a bean - what's not to like?

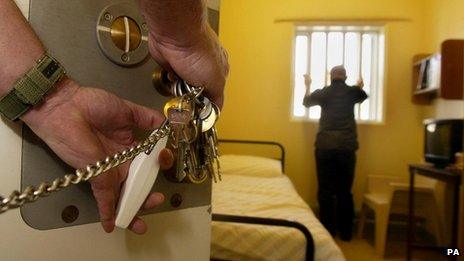

Chris Grayling's oft-repeated vision of "the old lag gone straight", volunteering to help those lost souls leaving jail with just £46 in their pocket, has all the life-affirming warmth of the classic redemptive drama. The only question would seem to be "why didn't we do this years ago?"

But there are questions. Away from the ministry and those organisations hoping to get a slice of the "rehabilitation revolution" action across England and Wales, there are some concerned voices.

What is being proposed is that private companies and charities will bid for contracts to supervise former inmates for a year after they leave jail. Those chosen by the ministry will only get paid if the ex-prisoners they take on stay out of trouble - payment by results.

Some of the supervision replaces what has been done up to now by the probation service, but the responsibility is being extended to cover 65,000 short-term prisoners who leave jail each year and currently receive no probation support.

Some charities may struggle to justify risking the funding to back Chris Grayling's vision

Among former inmates who serve fewer than 12 months, 58% commit further crimes within a year of release. With reoffending rates like that, you can see why the justice secretary is so keen to encourage fresh ideas in the delivery of rehabilitation services.

Imagine, then, that you are charity with an interest in using peer mentors (old lags gone straight) to help ex-offenders, and you are considering bidding for one of the contracts. Since, under current plans, you get paid nothing until the time you can demonstrate your charge has not re-offended, you will need to find some capital to get the project underway.

Charity trustees will, quite rightly, want to see evidence that your business plan is going to work before agreeing to dip into the institution's reserves. Here, though, you will encounter your first problem. There is very little evidence that mentoring works in cutting reoffending.

Analysis of mentoring schemes around the world, conducted by the Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion (CESI), found "there is no consensus that mentoring has a significant positive effect on mentees".

In her blog, external, CESI researcher Lydia Finnegan recently summed up the shortage of evidence behind the justice secretary's big idea: "When referring to the mentoring that many voluntary organisations provide, Grayling said 'I strongly believe it is making a real difference'."

Faith, however, is not the same as hard science, as the blog points out. "We found that evidence to support the efficacy of mentoring when measuring hard outcomes, such as its effect on employment and re-offending, can be inconclusive," Finnegan writes.

It is not Dragon's Den, but it is doubtful that responsible charitable trusts or institutional investors will be committing wads of cash to a payment-by-results mentoring scheme for ex-offenders without good evidence that it can get those results.

There will be people who are prepared to invest, though. Private-sector companies like Ingeus, G4S and Serco - already providers of a wide range of public services - will be looking longer-term. The contracts may prove to be loss-leaders in the early years, but they may calculate it is worth the hit just to be players in the game.

The next question, though, is how much is all this going to cost? I am told there is as yet unpublished Ministry of Justice research on the logistics of the supervision programme that casts real doubt on its cost-effectiveness.

Hundreds of mentors will be required to support the released prisoners

It is a point also made by the CESI research. "The support, supervision and training needed by the co-ordinating organisation to ensure the smooth running of a mentoring programme for both parties, i.e. the mentors and the mentees, requires huge investment," it points out.

Of course it does. Think for a moment of what it means simply to ensure there is someone at the prison gates to meet every one of the 200 plus offenders released each day. Then add in the cost of managing the continuing supervision for each of your charges for a year. This is going to be expensive.

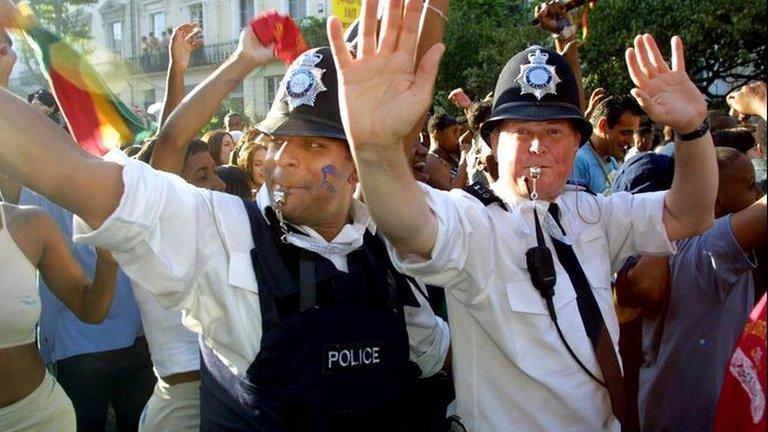

The government's hope is that a lot of the work can be done by volunteers - the Big Society meets Public Enemies. There are indeed some humbling stories of ex-offenders giving up their time to keep others on the straight and narrow. But are there enough of them? And are they all up to the job?

This is a serious point. Although the research on mentoring is troublingly inconclusive, it does suggest that professional, trained mentors tend to get better results than even the most willing and reliable amateurs.

People coming out of prison will often have a range of complicated problems - issues around mental health, housing, substance abuse, violence, literacy, employment. Giving them the best chance of staying out of trouble will require a lot of professionals to pull them through. You can't have a situation where an unpaid mentor goes missing.

Finally, there must be questions about the payment-by-results model after the bumpy start of the Work Programme. In a blog post today Matthew Taylor, chief executive of the RSA, external, sets out "several reasons to question whether PBR for probation will deliver".

It may be that, even without encouraging pilot studies or tested economic models, providers will be able to turn Chris Grayling's vision into a glorious reality. Few will not wish them well in their efforts.

But even if the financial risk is shifted from the taxpayer to private or charitable institutions, what the public really wants is a scheme that makes a real difference to the prospects of those who nervously sniff the air as they walk out of the prison gate. And that remains far from certain.

- Published24 April 2013