Suspects should have right to anonymity at arrest - Theresa May

- Published

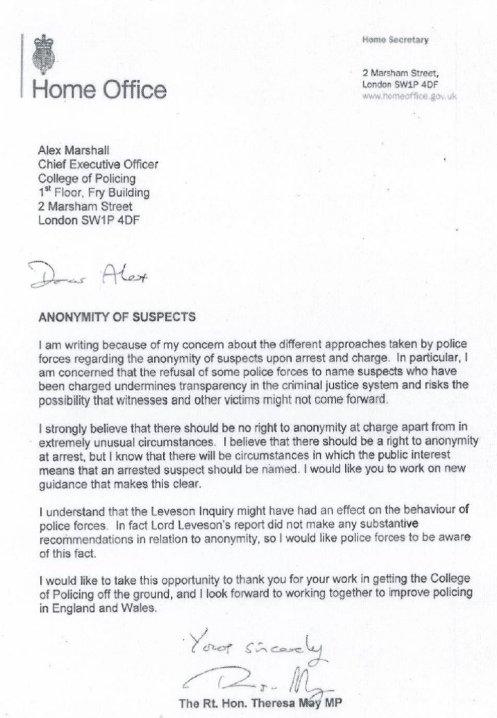

People who have been arrested should not normally be named until they are charged, Home Secretary Theresa May has said in a letter to police.

Her call comes amid concerns different approaches are being taken by forces in England and Wales.

It also follows some newspapers' claims that not naming suspects until they are charged amounts to secret justice.

But Mrs May adds that "there will be circumstances" when naming a suspect will be in the public interest.

The home secretary also insists that "there should be no right to anonymity at charge apart from in extremely unusual circumstances".

In her letter, addressed to the College of Policing, she writes: "I believe that there should be a right to anonymity at arrest, but I know that there will be circumstances in which the public interest means that an arrested suspect should be named."

The letter comes as the Association of Police Officers (Acpo) finalises new guidance on how officers should engage with the media.

A draft of the guidance, due to be approved by the college next week, states that, "save in exceptional and clearly identified circumstances, the names or identifying details of those who are arrested or suspected of a crime should not be released by police forces to the press or the public".

The exceptional circumstances could include a threat to life, the prevention or detection of crime, or a matter of significant public interest and confidence, according to the guidance.

However, senior officers have asserted that all suspects should be named when they are charged with an offence.

'Freedom of expression'

Some journalists have expressed concern that preventing police officers from revealing the names of suspects they have arrested but not charged amounts to a sort of secret justice.

Former Metropolitan Police commissioner, Lord Blair, has also said that naming on arrest can encourage other victims to come forward.

But the author of the proposed new guidelines, Chief Constable of the British Transport Police Andy Trotter, says he has spoken to the director of public prosecutions (DPP) about the potential risks of such a policy.

"I asked the DPP how defence lawyers would react to police arresting and naming a person and then asking if anyone has got any information about this person that might lead to a charge," he said recently.

Keir Starmer QC - the DPP - is understood to be content with the new guidance on anonymity, which stresses how "police forces must balance an individual's rights to a private life, the right of publishers to freedom of expression, and the rights of defendants to a fair trial".

Meanwhile, the Society of Editors, representing newspapers, has put out a statement suggesting that the police's decision to name the former TV celebrity Stuart Hall when he was arrested for sex offences demonstrates why anonymity may not be in the public interest.

Executive director Bob Satchwell said: "If Stuart Hall had not been named when he was arrested he might never have been brought to court. None of his victims knew one another."

Mr Trotter has since responded by pointing out that Hall was arrested at 10:00 BST and charged at 19:00 on the same day - during which time only one victim came forward having heard his name.

After his charge a further 12 people contacted the police.

'Atrocious'

"How do you select whose name to release?" Mr Trotter asks. "What is our criteria? An MP's son? A VIP? How many of the 1.2m people we arrest each year should we name?"

His view is that naming everyone arrested risks tarnishing the reputations of innocent people.

"People can be arrested one minute and de-arrested the next. We had someone who was arrested for the theft of a mobile phone who we later proved had found it and was trying to hand it in to police."

Mr Trotter is highly critical, though, of police forces which do not name individuals who have been charged.

When Warwickshire Police recently refused to name a former officer charged with the theft of £113,000 from the force headquarters they were widely condemned.

"It is atrocious that forces are not naming on charge," Mr Trotter says.

In a reply to the home secretary, the chief executive of the College of Policing, Alex Marshall, writes: "It is clear that a balance must be struck between the principle that a person is innocent until proved guilty and the understandable media expectation of openness."

- Published3 May 2013

- Published4 March 2013

- Published6 March 2012