Climbdown over Afghan interpreters' right to come to UK

- Published

- comments

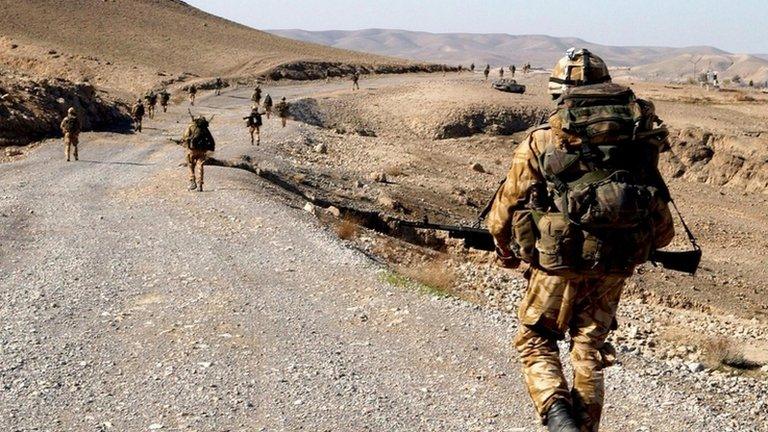

Up to 600 Afghan interpreters who worked alongside British troops are to be given the right to live in Britain

Britain's decision to give many of its Afghan interpreters the right to come to the UK has been welcomed by campaigners as a victory for common sense.

Could it be another example of British officialdom's ability to stand Canute-like in the way of taking decisions that are later regarded as no more than natural justice?

Lawyers for Afghans whose service could mark them out for murder if they stay in their country say they are happy with the government's decision, as far as it goes.

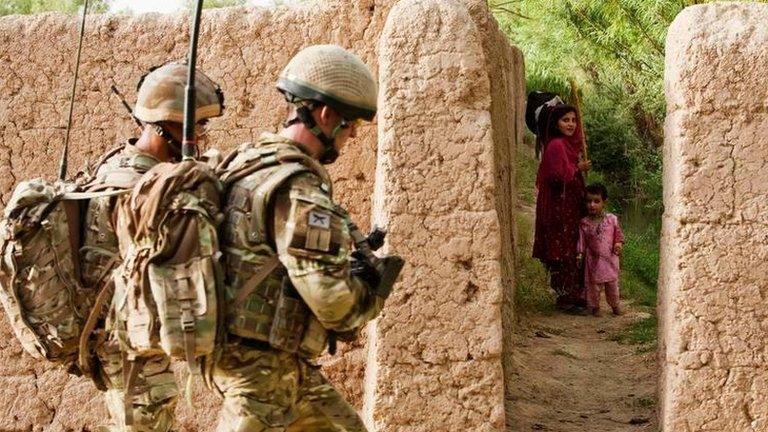

It would allow interpreters who had been employed for more than 12 months and whose work meant going "outside the wire" - in the war zone rather than just on bases - to have five-year British visas.

Having five years ago conceded the right to settle of Iraqis who had worked as interpreters for the British military, it seemed hard for Whitehall to argue that doing the same for Afghans was either setting a precedent or inconsistent with government policy, two of the favourite arguments of the naysayers.

Many of the Afghans had experienced intense fighting and some, like Mohammed Rafi Hottak, whose story we featured last year on Newsnight, had been seriously wounded while working with the British Army.

Many in the army assumed their interpreters would win the right eventually, so why obfuscate?

The interpreters' saga seemed another example of Whitehall or specifically the Ministry of Defence's ability to argue a point for years, deploying ever more ingenious stratagems to resist a campaigning group.

Several examples spring to mind - from the case of 1950s nuclear test veterans; to compensating soldiers for war wounds; or granting Gurkhas the right to settle in the UK.

Unsurprisingly the Ministry of Defence bridles at the suggestion that they run a uniquely unsympathetic bureaucracy, one guilty of Dickensian pettifogging.

They point out the issue of granting residence visas to interpreters was one in which the Home Office and Foreign Office were taking the lead.

I have also heard some ingenious reasons given today as to why this Afghan saga has gone on for as long as it has.

Say what you like about the British civil service, but in the best Yes Minister fashion it can marshal some fabulous self-justificatory arguments.

One of these is that the Afghan government had itself made representations against giving these interpreters entry to the UK.

Certainly it is true that many well-educated people have gravitated towards this work, including even some medical school graduates, because it is so well-paid and might offer hope of a life elsewhere.

It is also said that the multi-agency nature of this discussion made it much harder to agree a line.

One Whitehall official says the MoD was "hamstrung". Here too the argument has some force, since anyone who has followed Afghan policy in recent years has noticed that the "joined up approach" - so-called because it involves many different departments - often becomes glacially slow.

Perhaps the most intriguing subtext I have heard about recent discussions is that they became hostage to tensions within the UK's governing coalition.

In this version Tory hardliners on immigration lined up with the Home Office, while the Liberal Democrats and Foreign Office lobbied hard to open the door to the interpreters.

Whichever explanation holds more water, the debate now has been resolved in favour of the interpreters.

In my own travels among British forces in Afghanistan, I do not think I have ever encountered someone who argued their interpreters had not earned the right to come to the UK.

- Published22 May 2013

- Published22 May 2013

- Published1 May 2013

- Published3 May 2013

- Published11 February 2013