UK families speak of visa rules pain

- Published

"We need to know that you're not going to be living off benefits from day one of arriving here," the immigration minister said last year as he announced new rules to cut the number of people coming to Britain.

It is hard to imagine he had Kei Yamomoto in mind.

Kei is the Japanese husband of Marianne Bailey, a 35-year-old former senior designer for Yamaha, who now runs her own design firm. She is pregnant with Kei's baby, but her husband could be deported at any time.

They are just one of the thousands of families said to be prevented from living together in the UK because, on paper, Marianne does not earn enough to satisfy immigration officials.

"I'm giving birth in July," she says. "But they could take away my husband at any time - just pick him up."

'Ordinary person'

Rules that came into force a year ago mean any British citizen who wants to sponsor their non-European spouse's visa must be able to show they earn at least £18,600 a year, rising to £22,400 to sponsor a child.

The consequence for some has been an enforced and painful separation.

"How am I supposed to bond with my son?" asks one father. "I've only seen him twice since he was born. He's got a tooth coming through, he's turning around in his bed and I'm missing all these big events in his life."

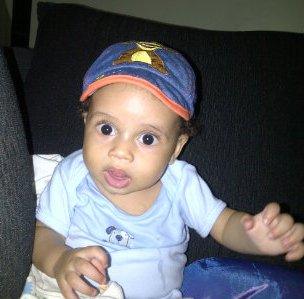

Douglas Shillinglaw lives in Kent, 3,000 miles away from his wife and six-month-old son Ethan in Lagos, Nigeria.

Douglas's son Ethan was born last December

Immigration officials say the £17,000 profit he made as a self-employed mortgage broker last year is not enough for him to sponsor his wife's visa.

He says he has already spent £2,000 appealing against the decision.

If an applicant wants to use their savings, rather than income, to show they have enough money to satisfy the new rules, they need £62,500.

"I'm just an ordinary person. I don't have those kind of savings." Douglas says.

"It seems like if you're middle class and you've got loads of money, then you can come in. They've got it totally wrong."

But financially better off people, like Marianne, have found themselves in a similar situation.

As well as her design company, she is a part-time university lecturer and an inventor with 20 patents to her name. She owns a number of properties and has a substantial Japanese pension, all of which, she says, takes her "well over" the £18,600 threshold.

But loopholes in the way officials assess an applicant's finances mean that three of her four sources of income are not counted. Her husband Kei faces deportation and would not be able to return to the UK for at least nine months.

"You have to have £62,500 savings in your bank account for six months before they'll count it. So even if we sold our house we wouldn't be in time for the birth," she says.

"I can't cope with a baby on my own."

Marianne says women are disproportionately hit by the new rules

A group of MPs and peers has been hearing stories like Marianne's for the last six months as it has looked into the effect on family life of the coalition government's new approach.

"These new rules are keeping hard-working, ordinary families apart," said Virendra Sharma, the group's vice-chairman.

He added: "I and others like me would not have been able to come to the UK to join my family if these rules had been in place then."

Ruth Grove-White, from the Migrants' Rights Network, who worked on the report, added: "Being able to start a family in your own country should not be subject to the amount of money you make."

The group points to the government's own estimate that - because of the new rules - almost 18,000 British people will be exiled from the UK if they want to live with their family.

'Economic dependency'

Ministers say they want people to come to Britain who can add to the UK's economic wellbeing and that they are reversing the policies of the previous government.

"Importing economic dependency on the state is unacceptable," the then immigration minister Damian Green has said.

The income thresholds have been set at a level officials believe mean families would receive no income-related welfare benefits.

One of those kept out of his native England by the new rules, 43-year-old John Cobb, has lived in Texas for the last four years.

His American wife Hayley earns more than $30,000 (£19,285) a year working for investment bank JP Morgan Chase.

But because she is the breadwinner and John works part-time at night while he looks after their baby son in the day, he cannot sponsor Hayley's visa and they are prevented from returning to the UK.

Only the earnings of the British sponsor are counted, so Hayley's income and the fact she could likely get a transfer to JP Morgan in England is irrelevant.

"If you fall in love with someone from a different country, it's tough," John says. "Especially when there's children involved, it's really hard."

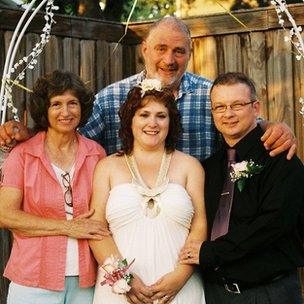

John and Hayley have been married for four years

They want nine-month-old Ryan to go to school and grow up in England with his cousins and half-sister. John is applying for jobs in the UK but knows if he is successful it would mean a painful separation from his wife and child until he meets the new criteria.

Last month Home Office ministers welcomed a fall in the number of people coming to the UK.

It was a major election promise and the numbers speak for themselves: 81,000 fewer people coming into the country this year than last. The number of people coming in on family visas is also down 16%.

London-born labourer John says he has no problem with the government's aims.

"Immigration is a problem that has to be tackled," he says. "But when they're stopping British citizens in legitimate marriages coming in, they need to work it out and change these rules."

A Home Office spokesman said: "Our family rules have been designed to make sure that those coming to the UK to join their spouse or partner will not become a burden on the taxpayer and will be well enough supported to integrate effectively.

"High-value migrants would not be refused because their British spouse or partner was not employed.

"They can meet the income threshold by having cash savings of £62,500 or through their own private income, for example from investments. We have also introduced greater flexibility for those holding investments to liquidate them into cash in order to meet the rules."