The secret world of the Old Bailey

- Published

Step through a door marked "do not wedge open" at the Old Bailey and you immediately start to descend into more than 1,000 years of criminal history.

Among the sights to be seen beyond the door, which is right by the entrance to the 74 cells in the historic court building, is an exposed section of rough stone Roman wall, which formed part of the defensive structure of "Londinium".

Even back then there were dungeons here, and later, in the 12th Century, the gatehouse in the wall, known as Newgate, became part of the infamous hell-hole which was Newgate Prison.

The prison walls can be seen built on top of the Roman wall.

"This is somewhere most people would not have liked coming," says Charles Henty, who has the ancient title of Secondary of London, Under-Sherriff and High Bailiff of Southwark.

Effectively he is the managing director of the Old Bailey, probably the most famous criminal court in the world.

Public executions

The building's smooth running is dependent on age-old infrastructure, including 1960's boilers and an electrical system described as "out of the ark".

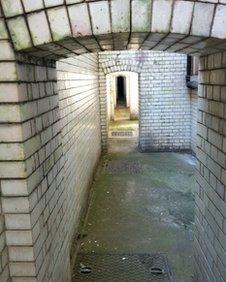

Dead Man's Walk led prisoners to the gallows

As a result, the City of London Corporation, which owns it, is embarking on a £37m modernisation plan behind the scenes.

Speaking in a small, one-windowed cell at the end of a long corridor, Mr Henty says: "This is the condemned man's cell. This is where you were held prior to your execution."

Executions were held out on the street outside the Old Bailey until 1868, and were a major crowd pleaser.

The best view was from the pub The Magpie and Stump, apparently.

The condemned man's cell has two doors; one through which you enter, the other through which you leave, never to return.

"You're hit immediately by this ghastly spectacle of seven or eight arches getting narrower and narrower," says Mr Henty as he steps outside.

This is known as "Dead Man's Walk", leading to the gallows.

'Out you went'

"In a very nasty way, it is designed to focus your mind," he says, "You are not coming back.

"You are going down this terribly dark tunnel, and you are going to meet your maker, and account and face retribution. You're going one way and one way only."

The end of the walk used to be known as the birdcage - a space with netting overhead, where prisoners got their last glimpse of the sky before they stepped out onto the gallows.

The Old Bailey's boilers, dating back to 1967, flummox electricians and engineers

"It was around this point where you would have heard for the first time the baying of the crowd outside, wanting blood," Mr Henty says. "And out you went, to the drop."

The Old Bailey has 18 courts which are usually busy trying some of the most serious crimes in the country.

But one of Mr Henty's biggest concerns is whether the giant 1967 boilers, which generate the heating and air-conditioning, will fail.

Looking like four great steam train engines, they leave most modern day engineers scratching their heads, and electricians are equally flummoxed when they see the wiring which controls them.

Out of action

"We have to make spare parts ourselves, and sometimes we find them on eBay," says Mr Henty.

"It wouldn't be very good for justice if it were all to collapse and go down like a pack of cards."

So refurbishments, including the installation of new boilers, will take place over the next 10 or 11 years.

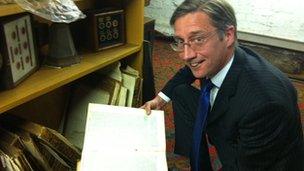

Mr Henty found the transcript of the trial of pirate William Kidd in an old store-room

Two of the 18 courts at a time will be out of action and much of the work will be done at night to avoid disrupting trials.

The City of London Corporation will pay £27m, with the rest of the £37m bill paid by Her Majesty's Courts and Tribunal Service.

The new boilers will be housed in the old coal cellar - a cavernous chamber deep underground with a hatch at one end leading down to the River Fleet - which runs under the building and down to the Thames.

It is an eerie place where the constant dripping of water merges into the rumbling of underground trains passing close by on the Central Line into St Paul's Station.

'The innocentest of all'

Mr Henty unlocks an old store-room nicknamed "the museum".

Its contents included old paintings of judges, a yellowing wig, some tin-hats from the Second World War looking like something out of Dad's Army, a typewriter and an old telephone exchange.

Then, flicking through some old transcripts of trials, we stumble across the 1701 trial of Captain William Kidd for murder and piracy.

"How about that?" cries Mr Henty in delight. He has clearly not realised some of the treasures which are down there.

According to the transcript of the sentencing of Captain Kidd and his co-defendants, the judge tells them: "You have been severally indicted for several piracies and robberies, and you William Kidd for murder.

"You have been tried by the laws of the land, and convicted; and nothing now remains, but that sentence be passed according to the law. And the sentence of the law is this: You shall be taken from the place where you are, and carried to the place from whence you came, and from thence to the place of execution, and there be severally hanged by your necks until you be dead. And the Lord have mercy on your souls."

Kidd replies: "My Lord, it is a very hard sentence. For my part, I am the innocentest person of them all, only I have been sworn against by perjured persons."

'Murder, murder, murder'

Above ground, in the grandeur of the Great Hall, with its 1907 columns and frescos is the better known Rumpole-like image of the Old Bailey made famous by the writer John Mortimer.

But as Charles Henty ran down the modern-day litany of human criminality in the security office ("murder, murder, murder, murder, rape, murder…") I couldn't help thinking that perhaps things hadn't changed so much over the many years the Old Bailey has been in existence.

"You cannot help getting involved in the history of this place, no matter how dark, terrifying, nasty or murky it is because we are still dealing with the consequences of crime, as we have been doing for over a thousand years," he says.