Human cost of failures in elderly care homes

- Published

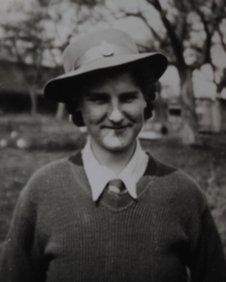

One family installed a camera in their mother's room because of their concerns over her care

Death rates in nursing and care homes for the elderly in England are to be monitored by the Care Quality Commission as part of a drive to root out poor care - but Panorama has found lots of gaps in the data. Reporter Alison Holt has been meeting a family that feels let down by the care their mother received.

When she was in her 80s, Kathleen Reid developed Alzheimer's. She had spent her war years in the land army, but her family could only watch as the disease progressively robbed her of her memories and her ability to look after herself.

When she could no longer cope she moved into a residential home which offered care for people with dementia: The Poplars, in Mountsorrel near Loughborough.

She was 88 years old. The home seemed ideal in 2008 when she moved in.

There were some issues, but her family say they became more concerned in the summer of 2010.

Daughter Joyce Zannoni, 62, said: "Every time I went up there was something not quite right. For example, her bed was wet, the floor was wet. And then the finding of medications in her drawers and in her clothing, so you know, she wasn't having her medication obviously."

The home says it checked Mrs Reid was taking medicines once aware of the problem.

Growing concern

But by the autumn of 2011, Mrs Reid's family were becoming increasingly concerned.

"I got there on the Saturday with my sister-in-law and we found flowers that were dead in a vase. She called me and said 'I think you'd better come up to the room, Joyce, because there's damp all over the wall.

Kathleen Reid was a land girl during World War II

"As you went up the stairs and opened a door, this stench just hit you coming through," she said.

The home says damp was only apparent after a downpour the night before.

But the family and health professionals were also worrying about Kathleen's weight.

A GP said she needed liquidised food - which she didn't always get - and she was moved to hospital.

Kathleen Reid died 14 days after leaving the Poplars.

A safeguarding investigation by the county council confirmed she had suffered neglect as her weight loss was not reported to doctors in a timely manner.

And the Care Quality Commission (CQC) concluded after an investigation at that time that there were major concerns about the care and welfare of residents and that some people went for long periods without adequate food or drink.

An inquest will investigate the cause of Kathleen Reid's death later this year.

The home told the BBC that Mrs Reid's weight loss was consistent with the progression of her illness; that she was encouraged to eat by staff and was provided with sandwiches and finger food throughout the day.

They deny there is any evidence of poor care or neglect, and say a new manager is in place and the CQC's most recent report shows improvements.

Failing care

But a third of all care and nursing homes in England do not meet the necessary standards, according to the CQC.

Mrs Reid's death did raise questions: the Poplars has room for 23 residents and there were at least 11 reported deaths at the home in the year she died - 2011/12 - compared to 12 over the previous three years.

The home told Panorama that a high proportion of the residents who died in 2011/12 were "terminally ill individuals in the later stages of their illness, who died in hospital", and this was reported to the regulator.

Mortality rates are now an alert to poor care in hospitals.

We asked the statistics expert Professor Sir Brian Jarman of Imperial College London to compare death rates at the Poplars to 501 similar homes we presented him with.

Professor Jarman found The Poplars was at the high end of the death distribution for 2011/12: that the number of deaths there was statistically significant compared against the other homes.

This could be a reflection of what was happening at the home. And if the deaths had been properly monitored, it might have triggered an inspection sooner.

Data gaps

The CQC is responsible for collecting and analysing data reported by care homes.

Panorama has been given exclusive access to this data and has found large gaps.

Care homes must by law report each death to the CQC when it happens; but Panorama found dozens of deaths in care homes that had reported none to the CQC in 2011/12.

Professor Jarman said: "I don't think it's really acceptable that you can have a home which is not recording whether a death occurred or not."

So how many other homes could have high death rates, hidden and undiscovered?

Professor Sir Brian Jarman helped expose high death rates at Stafford Hospital

Professor Jarman now believes care homes looking after a growing number of elderly people in our society need similar scrutiny to hospitals.

"Ten years ago there were 40,000 people died in care homes a year. Now there's over 100,000," he said.

"We're actually transferring care from hospitals, to a certain extent, to care homes."

The Chief Executive of the CQC, David Behan, says the organisation is now changing to identify poor care earlier.

He said: "Death rates are critical. We need to ensure that our databases are up to date and where they're not we need to challenge to do that.

"We don't think anywhere has got this cracked. Our experts will look at what you've done and if there's learning extracted we'll build into our methodologies."

Panorama - Elderly Care: Condition Critical on is on BBC One at 20:30 on Monday