Analysis: Whole-life tariffs ruling could spark another huge row

- Published

- comments

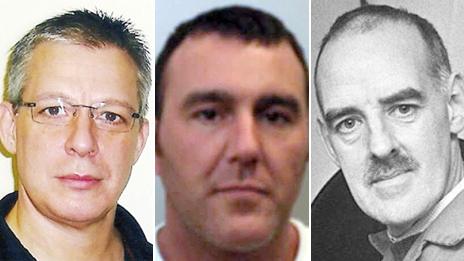

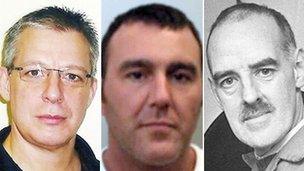

The appeal was brought by killers Jeremy Bamber, Douglas Vinter and Peter Moore

The decision by the European Court of Human Rights' (ECtHR) Grand Chamber on the whole-life tariffs given to murderer Jeremy Bamber and two other killers is really important - both legally and politically.

Let's start with the legals.

Judges in England and Wales have the power to impose a whole-life tariff (WLT) on the most serious and dangerous of criminals. There are 49 such prisoners in the UK. They include the Moors Murderer Ian Brady, Rosemary West and the three men who took their cases to Europe - Bamber, Douglas Vinter and Peter Moore.

The Strasbourg court has long accepted that if a state wants to lock someone up for life, then that is none of its business.

So this judgement was not about the state's right to lock up dangerous killers. The question was whether an WLT inmate should have the chance, during their long years inside, to try to show they are reformed and capable of making good with what little of their life they have left.

Back in January 2012, seven judges in the ECtHR's lower chamber ruled by four to three against the men, external, saying that their life sentence without the possibility of parole did not amount to inhumane treatment.

The case went up to the final Grand Chamber of 17 judges, including one from the UK, for a final say. Those judges reversed the lower court's decision, external by a majority of 16 to one.

The Grand Chamber said that a state can keep someone locked up for punishment, deterrence, public protection and rehabilitation.

But it said it was wrong that someone locked up in England and Wales does not have the opportunity to argue that they are rehabilitated.

England and Wales are in a minority when it comes to this lack of review - even within the UK. There is no provision for a WLT in Scotland. And in Northern Ireland prisoners given a whole-life sentence can already ask for a review.

Going abroad, the court says that a large majority of European states either do not impose whole-life sentences or, where they do, they usually have a review after 25 years.

So why did the court rule against the system in England and Wales?

Well it all comes down to what the judges say is a lack of clarity in the law - and the fact that a review once existed.

Until 2003, home secretaries had the power to review a prisoner's WLT after 25 years.

But the then government abolished that power as part of an attempt to take sensitive decisions about prisoners out of the hands of politicians.

The problem, says the ECtHR, is that if Westminster wanted to take politicians out of WLT reviews, why did it not give the power to a judicial body?

During the case, the government argued that ministers have a discretionary power to release WLT inmates on compassionate grounds, such as when someone was terminally ill, and that was sufficient.

But the judges said the discretionary power did not offer a prisoner the chance to prove they were reformed because release could only come in an inmate's final days.

So where does that leave the system?

The court has basically argued that the government should resurrect the old system, so that whole-lifers are told when they are jailed that they can hope - no more than that - to have a review hearing many years down the line.

It said that states should offer the review - and no more than that - because the grounds for keeping someone inside can change, and the circumstances may need looking at again.

The court added: "If such a prisoner is incarcerated without any prospect of release and without the possibility of having his life sentence reviewed, there is the risk that he can never atone for his offence.

"Whatever the prisoner does in prison, however exceptional his progress towards rehabilitation, his punishment remains fixed and unreviewable.

"If anything, the punishment becomes greater with time: the longer the prisoner lives, the longer his sentence."

The underlying point, the court argued, is that the thrust of modern penal policy has been to focus on trying to rehabilitate people - and that's why the lack of a WLT review is so odd in England and Wales.

The effect of the judgement is very similar to a recent judgement from our own Supreme Court, external.

In 2010 the justices ruled that people on the sex offenders register should have the opportunity to prove they are safe to be removed.

So what happens now?

Well, in legal terms, Parliament could solve the problem relatively easily by creating a power for either ministers, or the Parole Board, to review WLTs. Whichever way, the government has six months to respond to the court.

But the politics of this are massive.

Prime Minister David Cameron said he "profoundly disagrees with the court's ruling", adding he is a "strong supporter of whole-life tariffs".

As the court makes clear, it has no problem with the use of the sentence - but it knows that its relationship with the UK is at an extremely sensitive stage.

Whether it likes it or not, the judgement puts the court on yet another head-to-head collision course with ministers - and this time the row is arguably even more serious than Abu Qatada or Votes for Prisoners.

- Published9 July 2013