Fracking 'could put gas and chemicals' in drinking water

- Published

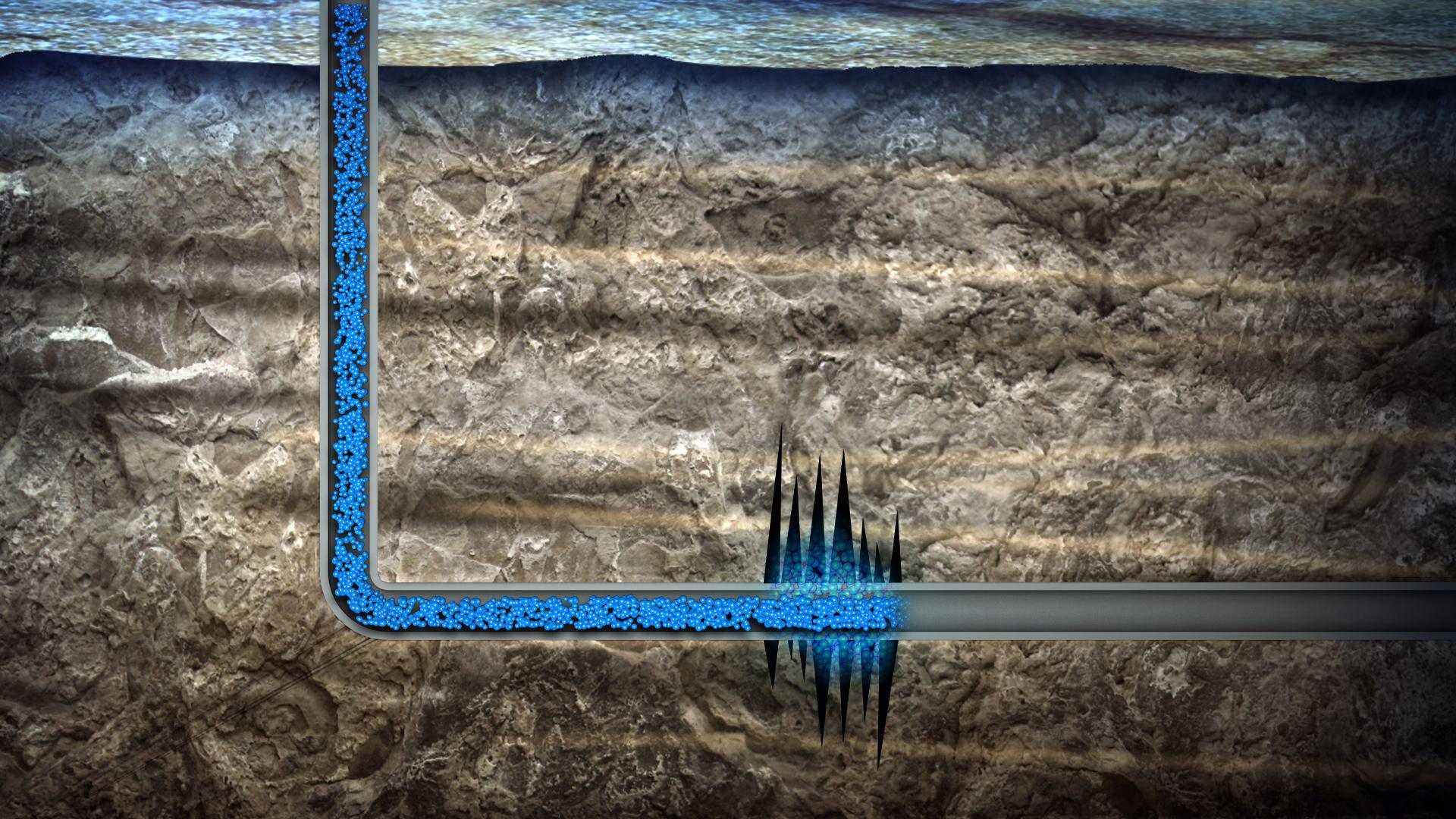

Cuadrilla started fracking in Lancashire in 2011

Drinking water could be contaminated with methane gas and chemicals due to fracking, water companies have warned.

Water UK, which represents all major UK water suppliers, said the shale gas extraction method posed a threat if not "carefully planned and carried out".

It also warned fracking's "huge" use of water could cause shortages in areas of low supply, like South East England.

Shale gas company Cuadrilla said there were no proven cases of aquifers being contaminated by fracking.

Dr Jim Marshall, of Water UK, called on fracking firms to hold "upfront discussions" with water companies "before fracking becomes widespread in the UK".

He said the water industry was not "taking sides" in the fracking debate, but wanted to ensure "corners are not cut and standards compromised, leaving us all counting the cost for years to come".

'No contamination'

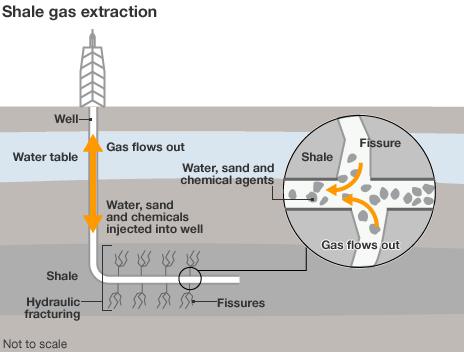

Fracking - short for "hydraulic fracturing" - involves drilling deep underground and releasing a high-pressure mix of water, sand and chemicals to crack rocks and release gas stored inside.

Water companies are worried the process could contaminate drinking water aquifers that lie above shale gas reserves.

Water UK said this could happen by gases such as methane permeating into water sources from rocks where it was previously confined, chemicals getting in through cracks created by the fracking process, or by poor handling of waste water on the surface.

A spokesman for Cuadrilla, which is carrying out test drilling in Lancashire, said: "There have been over two million hydraulic fracture treatments carried out globally, the majority in the US, and from that activity we are not aware of one single verified case of fracturing fluid contaminating aquifers."

The spokesman said the firm, which also wants to drill at a site in West Sussex, was "committed to the highest standards of well integrity".

He added that Cuadrilla was in "regular contact" with water suppliers and its supply of water "will never be prioritised over peoples' houses or farming".

A joint report, external by the Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering published last year said the risks could be managed effectively through "strong regulation".

Joseph Dutton, of Leicester University, told the BBC fracking presented "minimal danger" of water contamination if done properly, as the cracks it created were far deeper underground than aquifers.

He said leaks in well casings near the surface, caused by "poor workmanship" or the tremors associated with fracking, were the most likely cause of contamination.

Current EU and UK regulations "should ensure" no such incidents take place, Mr Dutton said - but he said the government "wants to speed up the process" and warned that loosening environmental controls, as happened in the US, would increase the risks.

Mr Dutton said the amount of water used in fracking varies, but each well uses at least a million gallons.

The Department for Energy and Climate Change said water companies "will assess the amount of water available before providing it to operators".

Speaking about the risk to water quality, a spokesman said there was "no evidence to date from the US of fracking causing groundwater contamination".

Fracking expansion

He said the Environment Agency would regulate use of chemicals in the UK on a "site-by-site basis and would order fracking to stop if a risk to groundwater was identified.

Anti-fracking campaigners protested outside Parliament in December

Widespread fracking has not started in the UK yet, but Cuadrilla began exploratory drilling in Lancashire in 2011 and many other possible sites have been identified.

BBC industry correspondent John Moylan said he expected the creation of 40 to 50 fracking wells over the next two years.

Large-scale fracking has reduced energy bills in the USA, but there is debate over whether the same would happen in the UK.

Chancellor George Osborne, who earlier announced tax breaks to promote fracking, said it had the "potential to create thousands of jobs and keep energy bills low for millions of people."

But Friends of the Earth said the government's "wild-eyed reverence for the new god of shale is completely misguided" and said there was "no evidence" it would reduce energy bills.

- Published19 July 2013

- Published16 July 2013