Daniel Pelka: The mistakes we keep making

- Published

- comments

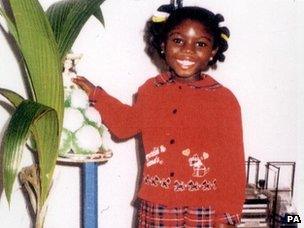

Daniel died age four after being beaten and starved by his mother and stepfather

The tragedy of Daniel Pelka is that he is not the first and won't be the last child to be tortured and killed, apparently hidden in full public view.

We wring our hands and promise lessons will be learned, but little Daniel's death bore many of the hallmarks of past failures. Tuesday's report echoes reports written many times over the past few decades.

"At times, Daniel appeared to have been invisible," says the Serious Case Review (SCR), noting that "there was very little evidence that Daniel was ever spoken to individually alone about his wishes and feelings."

When Ofsted pulled together the lessons, external from almost 200 serious case reviews involving the deaths of 60 children, they concluded that "too often the focus on the child was lost… their voice was not sufficiently heard."

The importance of talking to the children has been reiterated often and yet Daniel appears to have been quite alone, a vulnerability increased by his "poor language skills and isolated situation".

The report says professionals need to "think the unthinkable", rather than accept parental versions of what was happening. We've heard that many times before, too.

In his 2003 inquiry report into the death of Victoria Climbie, external, Lord Laming wrote of the need for "respectful uncertainty" among social workers; that they must be more sceptical and mistrustful about what might really happening behind closed doors.

The death of Baby Peter Connolly, five years later, was cited as evidence that children's services did not learn that lesson. Social workers remained "over optimistic", as Lord Laming put it - too trusting.

Victoria Climbie froze to death after being forced to sleep naked in a bath

Those professionals with a responsibility to keep Daniel Pelka safe are said to have fallen victim to that same "professional optimism". Today's review talks of their naivety, of how the manipulation and deceit of Daniel's mother "were not recognised for what they were and her presenting image was too readily accepted".

"The 'rule of optimism' appeared to have prevailed," the review concludes.

Almost exactly the same was said about the professional response to Peter Connolly's mother. She too was deceitful and manipulative and her little boy may also have died because agency workers were too quick to believe her stories.

Ofsted's review of serious case reviews, external makes exactly the same point. Again and again there was "insufficient challenge" by those professionals involved, the statements of parents or others in the family accepted at face value.

There's another theme that emerges from Ofsted's review of child abuse tragedies. Different agencies held different information but didn't talk to each other. And, of course, that was precisely what went wrong with Daniel.

Classic warning signs - domestic violence, alcohol abuse - were not flagged so doctors and teachers could not get a full picture of how chaotic and abusive family life had been.

When Eileen Munro published her review of child protection for the current government in 2011, she emphasised, yet again, the importance of a system in which encourages "professions to work together well in order to build an accurate understanding of what is happening in the child or young person's life, so the right help can be provided".

The room - with door handle removed - in which Daniel was regularly locked

One thought emerging from Tuesday's SCR is to make it mandatory for professionals to report every suspicion that a child may be being abused or neglected. It is an approach that already operates in Australia.

This seems an attractive idea at first sight, ensuring that warning signs don't get ignored and that the various dots of a child's life can be joined up.

But social workers and others may be cautious about introducing mandatory reporting in case it produces so many warnings - many of them unfounded - it blinds professionals to the most serious abuses.

There is no easy way to protect children but it seems we make the same mistakes again and again - well-meaning professionals overly optimistic and not talking to each other.

Endless reviews and reports attempt to tweak the protocols and procedures to prevent those mistakes, but then you risk a tick-box culture in which individuals are not permitted to use their professional judgment or common sense.

The real tragedy of Daniel Pelka is that we may simply not be able to prevent more children suffering and ultimately dying, hidden in public view.