How grease and fat from sewers can fuel your home

- Published

Last month, a "fatberg" the size of a double-decker bus was found under the streets of south-west London. But what causes them and how are they tackled?

Around 360,000 tonnes of oil and grease are flowing through the UK's sewerage system each year, creating a fat problem to solve.

Just as fatty food swells the circumference of our waistline, it narrows the circumference of our sewage pipes, threatening blockage and back-up.

If all the fat, oil and grease we wash into our drains every year were to coagulate in one place, it would create a "mega-fatberg", enough to fill an ocean-going supertanker or dwarf the Titanic.

Piers Clark, the commercial director of Thames Water, says he has seen a significant increase in the problem over the last generation.

"The modern diet has a much higher fat content than in the 60s and 70s. There are 111,000 food establishments in London - a number significantly higher than 10 years ago."

The Greater London Authority estimates there, external are 8,273 fast-food shops in the capital.

And beneath the streets, near Trafalgar Square in central London, Thames Water is well aware of the problem.

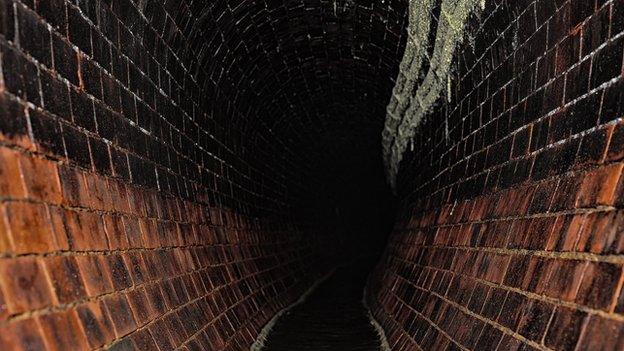

In Victorian sewers big enough to stand in, greasy sludge is sticking to the bricks at water level.

Carved-off chunks, squashed between (gloved) fingers, have the feel of hard butter, the look of lumpy Plasticine and the smell of... well, you can imagine.

Robert Smith, who delights in the title of chief flusher, says that a fondness for a high-fat diet is not the only problem.

Wet wipes and earbuds give the grease some structural bondage, which is what caused the berg beneath Kingston upon Thames this summer and a two-mile-long fat "snake" discovered coiled beneath Leicester Square a few years ago.

Once discovered it all goes to landfill - until now.

Video footage shows the 'fatberg' inside the sewer, as Gordon Hailwood from Thames Water explains

Thames Water will shortly be burning it to keep the lights on. According to Mr Clark, it is a first.

"We'll be harvesting fat from our sewer network and turning it into power in our facility in east London where we hope to provide enough for 40,000 homes," he says

To do this they'll need to extract 30 tonnes of fat a day, refine it to create a biofuel for use in a specially-built power station producing nearly 130 GWh of electricity every year, according to Ofgem estimates, external.

Nutritionist's nightmare

The leftovers from the appetite for greasy food do not just go down the drain, as evidenced on the outskirts of Hull at Brocklesby Limited.

Robert Brocklesby's business relies on what most people see as waste to sell on in the biofuel market

Its yard looks like a nutritionist's nightmare; pungent drums of old crisps mixed with sweating kebab meat and chicken legs, pallets laden with mayonnaise and rancid butter and a paddling pool of pig fat, courtesy of the pork scratching factory.

Owner Robert Brocklesby describes with some pride how much of this would once have been waste taken to rot in the ground, but now is all reused.

"There has been a huge change with regard to used oils and fats being used in the biofuel market," he says.

"There has been a real shift in the last decade or so as the demand for vehicle fuel is insatiable."

Even those tiny butter packs served with hotel breakfasts are shredded, steamed and separated into water and oil. He reckons they produce around 80 million litres of biodiesel here, enough to fill the tanks of around one-and-a-half million cars.

But they also produce lubricants, waste water for bio-digesters and fertiliser. Everything, he believes, has a use.

Where waste is put and where fuel is found are two of the most heated environmental debates of the moment, so burning fat to keep the lights on or former pork scratchings in pistons seems like the perfect answer.

There are about 40,000 fat blockages in London's sewers annually, according to Thames Water

But at the University of Wolverhampton, microbiologist Dr Iza Radecka is trying something even more ambitious - making plastic for body implants from old chip fat.

"We start with something that is horrible and dark and greasy," she says.

"We make this beautiful, white, flaky material which can be used for biomedical applications - a bio-plastic for implants or a scaffold for tissue repair."

She says old cooking oil is good because it is cheap, biodegradable and - with the addition of the right microbes, fermentation and ultrasound - has a much higher yield of polymer than raw glucose and fructose.

This means that waste cooking oil could actually be more efficient than its raw ingredients.

It would be a delicious irony, so to speak, if the waste oil from the chips which clog my arteries could one day build me new ones.

Costing the Earth: Burn that Fat is on BBC Radio 4, Wednesday, 25 September at 21:00 BST, or afterwards on iPlayer

- Published6 August 2013

- Published15 April 2013

- Published9 March 2012

- Published25 December 2011