Is online crime really rising?

- Published

- comments

On Tuesday the Labour Party sent journalists what they said was an "extract from Yvette Cooper's speech" to conference.

In the time-honoured way, her briefing team revealed something of what she was "expected to say" on Wednesday. The extract, reported on the BBC and in many of the papers, included the claim that, when it comes to online crime, "the problem is escalating by the day".

On the day, that line was no longer in her speech. Instead, the shadow home secretary put the claims in someone else's mouth. "Police say it's growing exponentially," she said this afternoon.

And I suspect the change is down to me.

On Tuesday afternoon, I challenged Cooper's office to justify her statement on "escalating" cybercrime because the official body set up by the Home Office specifically to monitor fraud, including e-crime, does not make the same claim.

In fact, the National Fraud Authority's latest annual fraud indicator (AFI) is very circumspect. "The AFI does not indicate whether fraud losses overall have increased or decreased," it says. "Year on year comparisons are not meaningful… and cannot sensibly be used to trend or draw conclusions on the 'growth' or 'decline' of fraud over time."

Because politicians inhabit a world that really believes the Home Office has the power to change crime trends, it almost becomes the democratic duty of shadow home secretaries to be the sirens of doom, warning about rising criminality and social collapse.

For decades this was quite an easy job. Crime really was rising. But since the mid-1990s, this has become much harder because crime levels have been falling in almost every category.

As shadow home secretary before the last election, Chris Grayling got into hot water for suggesting that violent crime was soaring. David Cameron said the same thing. Now, of course, the prime minister is happy to take credit for falling crime figures.

David Cameron: Changing his line on crime statistics?

So Ms Cooper cannot just quote the crime stats to attack her political opponents. Indeed, she said today that "everyone welcomes the 20-year drop in recorded crime".

The original draft of her script appeared to have found a new line of attack - crime isn't falling, it is changing. The government is failing to adapt to the new and growing criminal threat.

It feels right, doesn't it? All those dodgy emails promising lottery gazillions if you just send your bank details to some nice chap in Nigeria are an almost daily reminder of the risks of cybercrime.

Every time your bank declines your card because of a "security check", or your computer security system alerts you to a new malware attack or virus, the invisible threat of electronic villainy is raised.

Cooper's team had obviously scoured the cuttings to find stories of victims of cyber-crime for her speech: "The pensioner who lost his savings wiring help to a friend he thought was stuck abroad in distress. The family who lost hundreds of pounds on a holiday which never existed."

Cybercrime is undoubtedly a very significant problem, but is it getting worse? The difficulty is that we only recently started trying to count it and, as we look harder for it, we discover more of it. But that doesn't mean it is rising. It may actually be falling.

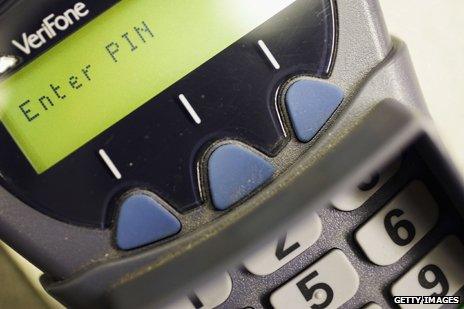

Remember how credit card fraud increased during the noughties, only to fall away again after the introduction of chip-and-pin? The opportunity for cybercrime increases as we live more of our lives online, but we may be getting better at stopping it and smarter at avoiding it.

How many people really fall victim to the email from the friend "struck abroad in distress"? Recent analysis of crime survey data suggests that 56% of adults in England and Wales had received unsolicited communication from someone they'd never heard of, requesting money.

But the ONS paper goes on to say that "the number of victims is too small to produce any reliable estimates of the scale of victimisation".

When the Home Affairs Select Committee looked at trends in e-crime, external this year they concluded that "the incidence of e-crime is high and increasing". But support for the second part of that statement was not terribly convincing.

Evidence from RSA and Symantec "attest to an increase in the threat from e-crime", they said. That will be two of the corporate computer giants that make money flogging security software, then.

There is a risk from hackers and viruses and malware attacks, but companies who make their billions on the back of people's cyber-fears are not the most independent of sources.

Indeed, an academic paper written for the European Network and Information Security Agency a few years ago complained that "the number of phishing websites, of distinct attackers and of different types of malware is persistently over-reported… when in fact a small number of gangs lie behind many incidents and a police response against them could be far more effective than telling the public to fit anti-phishing toolbars or purchase antivirus software".

I am slightly doubtful as to where Cooper's anonymous police officer got his "exponential" increase from. We need to be alert to the risks of crime online. And there may be an argument for greater government focus on the issue.

But it is just as important to retain a sense of perspective on the risk. Otherwise, millions who might really benefit from using the internet will be put off because they think cyberspace is like the Wild West.

UPDATE 17:25

My piece has now elicited the following response from Yvette Cooper on Twitter: "much as I'd love to credit you for my speeches mark, was more concerned w length. Happy to repeat e-crime going up day by day."