Loneliness: 'I'd describe myself as a recluse'

- Published

Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt has said it is a source of "national shame" that as many as 800,000 people in England are "chronically lonely".

Here some people share their stories of feeling isolated and alone in modern society.

Vera Clempson, 82, from Manchester

Vera Clempson says speaking to young people helps keep her young

"I used to run my own business, I had shops - cafes, chip shops and even a toffee shop in the war when I was very young. I was used to seeing lots of people every day and having lots of conversations all the time.

I love company and miss that terribly now. The last two years in particular have been very bad.

My son works and sees me as often as he can - work permitting - and my daughter-in-law visits me once a week. I have a cleaner that comes in once a week and a dear girl who comes to keep me company.

I know I am lucky, that there are people worse off than me. But it's in between those visits that there are a lot of hours to fill in the day.

My husband died on Christmas Eve in 1970 - he was only 40 and I was 39. I used to have a lot of friends, many of them were younger than me, but as time goes by, more and more of them seem to succumb to cancer or some other illness and they have died now.

But I'm still here. It doesn't seem fair though. My brain is fine but my body is giving up. I just keep going and I worry in the future it will only get worse.

I don't fancy going to these social clubs for older people - half of the people in there have lost their minds. I love speaking to younger people though, about anything. It keeps me young.

I tell everyone to go and live their life while they are still fit and healthy."

Larrie Wright, 51, from Watton, Norfolk

Larrie Wright says he feels like a prisoner in his home

"I would consider myself as chronically lonely - my computer and television are my only windows to the outside world.

I'm ex-forces and suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). I see my mental health nurse every two weeks and that is basically my only contact with anybody.

I don't have any family and I live in a rural area in Norfolk. There isn't much to do here. Everyone here is much younger than me and I see age as an definite communication barrier, and there are also lots of Polish people moving into the community.

My PTSD makes me wary of people. When I first left the forces in 1989 I became a Tesco manager and had lots of friends, but my social status dropped when I left the job due to health reasons and people didn't want to speak to me as much.

I got this social housing in Norfolk two years ago. I want to move to a larger area about 12 miles away where there is a cinema but I can't do that because I don't meet the criteria and I'm not a high enough priority. It's a Catch 22.

I am very unhappy and depressed to the point of clinical depression. I see people walking around hand in hand and I want that. But it only makes it worse, and I feel more resentment towards others.

I'd describe myself as a recluse. I'm almost a prisoner in my own home and it's been like that for two years.

It's not just a pensioner thing. I'm 51 and considered not elderly at all, therefore not looked at as a person needing care."

David Howes, 67, Rochester, Kent

David Howes says he finds evenings the hardest time of the day

"I am only 67 and I have a nice home and all the trappings.

But I have neighbours who don't speak and I have no family at all. I have a friend who lives a few miles away but he never gets in touch. No-one visits, no-one rings. It's been like this for eight years.

Every day is the same and I have to discipline myself to cope with it. I exercise, I do some gardening and my housework and go walking.

The only time I see someone is when I shop. I put on my best clothes to go shopping and always look very smart. But once I get home there is no escape from the loneliness.

I go to bed at 8.30pm as I'm so fed up with the day - evenings are just terrible.

This will be the seventh Christmas on my own and my birthday is Christmas Eve. If I got ill I do not know what would happen.

You don't have to be really old to know lonely. People who are surrounded by family have no idea."

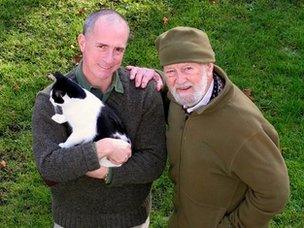

Richard Bates, 55, is a full-time carer for his father Fred, 88, in Chichester

Richard Bates quit his job to be a full-time carer for his 88-year-old father

After my mother died about a decade ago, my father carried on living in the family home - with us seeing him a couple of times a month - until he fell in the snow.

Only then did I realise how courageous he was, and stoic, but moreover how lonely. It got worse when his cat died and he had no companionship at all apart from the television. He was in a spiral of despair but was pretending he was coping.

I have been his carer for four years since his fall - living in his home, taking him out, keeping him mobile, and catching him when he fell again recently. He's got vascular dementia but apart from that he's physically mobile. His memory of me and his personality is substantially there.

I'm 55 and used to have an active social life and ran my own business in London. By moving here I've lost my earnings and receive carer's allowance but it doesn't even cover the rent in my own home.

Many other people around the country serve as unpaid carers and would endorse Mr Hunt's ideals, but wish he would give us better financial support.

I keep my dad company and am his only friend. We often think our parents are a pillar of strength, especially when they don't let on how lonely they are.

It's only in retrospect that I realise how empty his life was and how abandoned by society old people often are. It made me feel an aching sadness when I realised how he'd felt.

- Published18 October 2013

- Published8 April 2013