Kim Philby: The spy who went into the cold

- Published

Kim Philby is buried in Moscow's Kuntsevo cemetery, not far from Leon Trotsky's assassin

Fifty years ago one of Britain's most infamous spies, Kim Philby, defected to the Soviet Union. The unresolved questions surrounding his defection reveal blind spots in the British ruling class that made it vulnerable to KGB penetration.

On a stormy night in January 1963, Kim Philby skipped a dinner party in Beirut and boarded a freighter bound for the Soviet Union.

He had been working for the communists since he was 22, but instead of a hero's welcome, he was shut away in a flat near Moscow city centre and allowed nowhere near the organisation he had served for so long. Even the Russians were suspicious that he had got away scot-free.

At the time, his defection made little news in Britain.

On the face of it, a middle-aged journalist with a tendency to drink too much had simply gone missing.

In a letter to the Foreign Office, the British ambassador in Beirut hazarded a guess that he had gone off on what he politely called a "lost weekend".

Six weeks passed before his own newspaper, the Observer, even mentioned his absence. But when the news did break in the summer it started a slow-burning bonfire of recrimination over the way British intelligence was run.

Philby was a leading member of the so-called Cambridge spy ring, a group of well-educated young men who all joined the Soviet cause in the 1930s.

At the height of his clandestine career, he was both working for the KGB and in charge of MI6 operations against the Soviet Union.

He did come under suspicion after Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean defected in 1951, and had to resign from his job.

But the spy-catchers in MI5 failed to pin anything on him, so his friends in MI6 rallied round to find him work as a journalist in Beirut and even re-employ him as an occasional secret agent.

Beirut was a city awash with spies when he arrived there after the Suez crisis of 1956, and it was not long before Philby was back in business as a double agent.

Parties and drink played a large part in his life. Whether he was picking up information for his editors or his spymasters, he never seemed to be far from a bar.

His favourite - Joe's Bar - was a few yards from what was then the British embassy. In those days the Foreign Office paid their staff a special allowance for renting an extra home in the hills to escape the heat of the afternoon.

Just before lunch, diplomats would emerge from the embassy "for a few stiff ones" at Joe's Bar before setting off for the hills.

Philby was always at a table near the back, one of them told me, apparently speechless with alcohol but listening carefully to all the gossip.

In 1960 one of Philby's best friends in MI6, Nicholas Elliott, was sent to Beirut as head of station.

Kim Philby lived in a fifth floor flat in this building in Beirut

Elliott was an Old Etonian with a penchant for risque stories. When he arrived, he called the young embassy press officer in and told him Philby was a man who could be trusted with information.

For a couple of years, Kim seemed to be back in the fold, rumours about his treachery forgotten.

But in London a storm was brewing. It had started with a chance conversation in Tel Aviv.

A reliable source had revealed that she had once been approached by Philby to spy for the Russians. That was passed on to a tiny cabal of MI6 and MI5 top brass who concluded they now had enough evidence to extract a confession from him.

But instead of sending a professional interrogator from MI5 they decided at the last moment to ask Philby's old pal Nicholas Elliott to handle it.

The confrontation was in the middle of January 1963. A few days later, on 23 January, Philby disappeared.

When it was revealed he was in Moscow, "sources" quickly let it be known that before he fled he had confessed, verbally and in writing, as though in some way the fact that he had not been arrested was of less material importance.

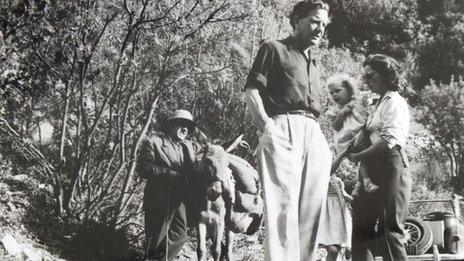

Philby at a picnic near Beirut shortly before he defected to the Soviet Union

But as the years rolled by, journalists and historians unearthed a different story. Yes, there had been a confrontation, but the recording of the confession was apparently drowned out by traffic noise. And the written confession was apparently not worth much either.

In other words, the operation had been bungled.

One possibility of course was that they had wanted him to run to avoid more embarrassment back home, but whether that is true or not, what haunted the intelligence services was that he had obviously been tipped off in advance.

Who else among them was a spy? - they asked for decades afterwards.

My theory is that the tip-off could have come from Anthony Blunt, who was later revealed to be a traitor but was then a confidant of at least two members of the small group who knew what was going on.

Anthony Blunt, who was keeper of the Queen's pictures, was unmasked as a spy in 1979. Did he tip off Kim Philby on a bogus orchid-hunting trip?

In December 1962, he went on a private trip to Beirut to stay with his friend, the British ambassador.

He said he had come to find a frog orchid. But the orchid expert at Kew Gardens told me frog orchids do not grow in Lebanon, so he must have been lying.

I cannot prove that theory, any more than other spy hunters can prove theirs.

The definitive answers may lie in the files of MI6. But even after 50 years they have not been made public. Why? For reasons of "national security".

They would say that, wouldn't they?

Watch Storyville: The Spy Who Went Into The Cold on BBC Four at 22:00 GMT on Monday 18 November or catch it later on iPlayer.