Spy fact mirrors fiction with agency chiefs in televised grilling

- Published

Dame Judi Dench plays the head of MI6 in Skyfall

When Parliament's Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) quizzes the three heads of the UK intelligence agencies later it will be the first such meeting in public.

Fact often mirrors fiction in the world of spies.

Before Thursday, if you had wanted to see British spy chiefs appear before parliamentarians and the cameras, your only opportunity would have been in the last James Bond film, Skyfall.

Dame Judi Dench, playing M, had just lectured the assembled audience about why spies were still needed in the modern world when the villain of the tale burst into the room with guns blazing.

Security is going to be tight in Parliament but no-one is quite expecting such a dramatic afternoon.

Andrew Parker was named as the new head of MI5 earlier this year

The real-life hearing may be missing Dame Judi but it still will, in part, be about theatre and performance.

Despite the presence of so many people who know so much, no-one should expect any secrets to be spilled.

That is not the intention of the hearing - it is, rather, part of a wider effort both by spies and by those who scrutinise them to provide greater transparency about their work.

And if any secrets do somehow slip out then the two-minute time delay on the TV feed means the outside world may well be prevented from hearing them.

The hearing is only an hour and a half long; so the level of detail will be limited.

Secrets spilled

Each head will want to discuss how they see the threats and explain what their organisation is doing to counter them.

The three spy chiefs are all different characters.

The chief of MI6, Sir John Sawers - often known as "C" rather than M - spent most of his career in the Foreign Office; so he is not a stranger to the TV cameras.

Andrew Parker, from MI5, is new in the role but has been in the upper echelons of MI5 for many years.

Sir Iain Lobban, of GCHQ, faces the hardest task.

Leaks by Edward Snowden have drawn the work of GCHQ into the spotlight

He has been running his agency for longer than either of the others but historically it has been the most secret and the least outward-facing.

Or at least it was until the past few months, when former US intelligence contractor Edward Snowden began spilling its secrets, drawing its work into the spotlight as never before.

The spies have already been giving evidence to the committee in private for many years and that is where the real detail will be discussed.

But the decision was taken recently that this was no longer sufficient.

Thirty years ago, the intelligence agencies existed almost entirely in the dark.

There was no legal footing for them and no form of accountability - other than ministerial sign-off - until 1994.

The names of the heads of the organisations would not even have been widely known.

Snooze factor

The spies began to speak in public in the 1990s in carefully controlled settings but this hearing marks a significant milestone.

Modern concerns such as terrorism and cyber-security are inherently more public-facing than the kind of monitoring of the Soviet Union that occupied so much time in the Cold War.

Public notions of transparency also mean the days of staying out of the limelight have gone.

Ex-Guantanamo inmate Binyam Mohamed challenged ministers to reveal what they knew about torture

American spy chiefs do appear before Congress publicly but the hearings can be pretty anodyne.

When the British committee watched some recordings of their US counterparts some of them had second thoughts about going public - they feared the snooze factor might be too much.

So a key question will be how far the members of the ISC want to go in challenging the spy chiefs and giving them a hard time.

That is important because it is not just the spy chiefs who people will be watching closely.

The committee itself is also under scrutiny and this performance will be crucial in defining whether it really is capable of holding the intelligence agencies to account.

Its performance in the decade after 9/11 has been criticised.

A number of key controversies have swept through Britain's intelligence community - Iraq's absent weapons of mass destruction, whether the 7 July 2005 London bombings could have been prevented, and the UK's involvement in the rendition and transfer of detainees, to take the three most high-profile.

But in each of these areas, the ISC has underperformed.

Patchy record

The details about Iraq came out thanks to the Butler Inquiry and now the Chilcot Inquiry - not the ISC's own report.

On 7/7, the committee had to go back and re-report after gaps in its initial findings.

And, on rendition, the record is also decidedly patchy.

The ISC's initial conclusions were challenged by evidence about British resident Binyam Mohamed who spent four years at Guantanamo Bay.

Its findings was also called into question more recently over MI6's involvement with the transfer of two men to Libya - evidence which emerged thanks to the collapse of the Gaddafi regime rather than the oversight of the committee.

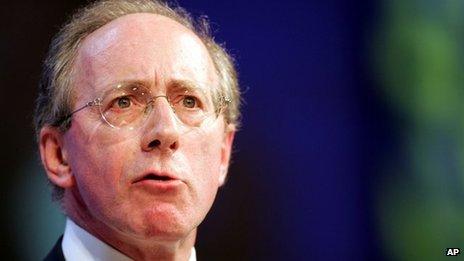

Sir Malcolm Rifkind took over as committee chairman in 2010

The Snowden affair has raised new questions - including about whether the committee was too quick to defend spies rather than oversee them.

The past problems were acknowledged by the committee's chairman, Sir Malcolm Rifkind, when he took over in 2010 and a number of reforms were introduced under the Justice and Security Act.

The ISC can now demand information rather than request it and its remit has been extended formally to cover operations rather than just the management of the agencies.

The committee's investigators can go into the agencies and look for material rather than take what they are given - something they have already done.

Parliament - rather than No 10 - is also being given more power over the composition of the committee itself.

Finally, we have the public hearing itself - the most visible sign that, in the spy world, times have changed.

- Published7 November 2013

- Published17 October 2013

- Published11 October 2013

- Published9 October 2013