How often are captured enemies killed?

- Published

A modern-day staging of Henry V and the Battle of Agincourt, the famous English victory of 1415

How often do armed forces personnel kill the enemy they capture?

The conviction of a Royal Marine for the murder of a captured Afghan insurgent has made headlines because, by and large, we live in a society where it's assumed soldiers follow the rules of international law.

But anyone who has studied warfare will know that it has happened all too often in the past. In fact, there was a time when it was relatively rare to see mercy on the battlefield.

The norm was for the victor to wreak vengeance on the enemy, even after they surrendered.

The Battle of Agincourt in 1415 may be remembered as a famous English victory. But it's also where King Henry V ordered the execution of thousands of captured French prisoners.

It was a sign of the times, when armies thought little about what to do with those who were captured. The greater fear was that if lives were spared, they might fight another day.

Attempts to follow international rules of war may have put in place a moral code for treating prisoners humanely.

But there are still many cases of brutality in modern warfare. In 1940 at Le Paradis, outside Dunkirk, the German SS herded about 100 British prisoners into a barn and then just threw in grenades. Worse happened on the Eastern Front.

'Fog of war'

Military historian Robert Lyman says such executions on the battlefield are very common.

"Determining whether a person is killed in battle or executed in the aftermath is often only a product of time," he says. But he draws a key difference between actions taken in the heat of battle and those that can be viewed as cold-blooded murder.

That is how the killing of the Afghan fighter has been described. Or as the prosecution put it - an execution.

For those of us who watched the video in court of his final moments, there was nothing to suggest this was a tragic mistake made in the "fog of war".

Extract from helmet camera recording of incident in Helmand, Afghanistan

There was never any firefight between the Royal Marines and the insurgent. The armed Taliban man had already been taken out of the battle by the cannon of an Apache attack helicopter.

Severely wounded, he was left clinging to life.

From the first comments caught on the camera to those spoken by Marine A after he fired that final shot, there is no mercy, or even humanity. This was a cold, calculated murder away from the heat of battle.

And what is more, what happened went against everything combat forces are taught.

Practical lessons

The Geneva Conventions and the humane treatment of prisoners have been drilled into every British marine and soldier, both in the classroom and on exercise.

Each year, every member of the British military undertakes tests, known as MATTs, that remind those in uniform of the rules of war.

On pre-deployment exercises, they have practical lessons on how to deal with prisoners in line with the Geneva Conventions.

Even when in combat, everyone in uniform carries a Tactical Aid Memoir - a manual that includes a section on how to treat those captured in battle. All this training was ignored.

Can excuses be made because of the Taliban's own cruelty?

After Marine A fired that shot he could be heard saying: "It's nothing you wouldn't do to us."

His defence included evidence that the Taliban had earlier hung from a tree the body parts of British soldiers killed in a roadside bomb, as if they were trophies.

Fight for survival

The actions of the enemy can clearly have an effect on how they are treated themselves.

In his book Their Darkest Hour, the author Laurence Rees interviewed a former US marine who fought the Japanese in World War Two.

"Once 30 or 40 of them came out with their hands up. They were killed on the spot because we didn't take prisoners," he said.

And the reasons for his actions? He said the Japanese had brutalised, murdered and tortured US marines they had captured.

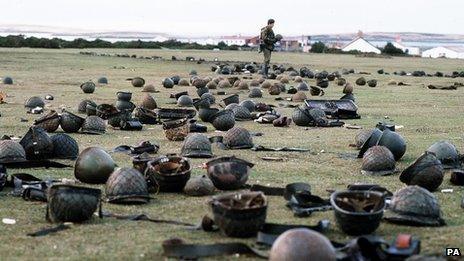

Goose Green in the Falklands, where Argentine soldiers laid down their arms

But the war in Afghanistan was never the same fight for survival. It was about much more than defeating an enemy. It was supposed to be about values and ideals, winning hearts and minds.

So there is little sympathy from others who have served in uniform.

Tony Banks fought in the Falklands War with another elite unit - the Parachute Regiment. He too witnessed horrors - including comrades killed by Argentine soldiers who had tricked them into thinking that they were about to give up fighting.

'Common humanity'

He says that partly explains why, in a later battle, a young Argentine soldier was shot when it appeared he might be trying to surrender.

But, again, he draws an important distinction. These were actions carried out in the heat of battle. To him, what happened in Helmand was both calculating and cold.

Why, he asks, wasn't "common humanity shown" to that wounded Afghan fighter.

As the English writer GK Chesterton said: "The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him."

- Published7 November 2013

- Published23 October 2013

- Published5 August 2013