10 dangerous things in Victorian/Edwardian homes

- Published

The late Victorians and the Edwardians lived through a domestic revolution. Theirs was a bold and exciting age of innovation, groundbreaking discoveries and dramatic scientific changes, many of which altered life at home in profound ways - including some that were terrible and unforeseen, writes historian Dr Suzannah Lipscomb.

Much of their ingenuity was a response to the challenges of living in the newly booming cities - in 100 years, the urban population of Britain had leapt from two million in 1800 to 20 million at the turn of the 20th Century. By 1850, London was the biggest city the world had ever seen, and such enormous concentrations of people posed brand new problems of feeding, watering and housing the masses.

In addition, the newly enriched middle classes - whose incomes had risen as mass production meant the cost of necessities dropped dramatically - had more money to spend on luxuries than ever before, and those they purchased were designed to make their homes into comfortable, fashionable havens of domesticity.

Yet, many of the products they bought or inventive technological solutions they came up with were not only health hazards, but deadly domestic assassins. They were welcoming hidden killers into the heart of their homes.

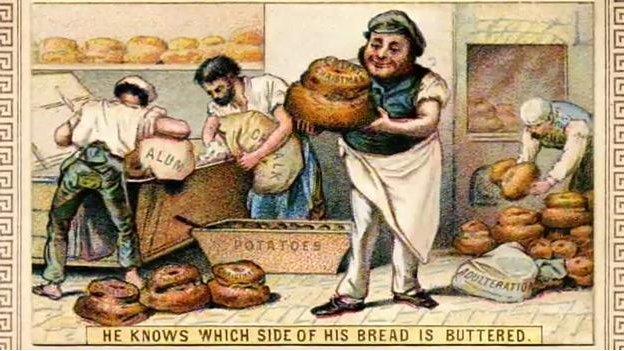

1. Bread adulterated with alum

When basic staples like bread started to be produced cheaply and in large quantities for the new city dwellers, Victorian manufacturers seized on the opportunity to maximise profit by switching ingredients for cheaper substitutes that would add weight and bulk. Bread was adulterated with plaster of Paris, bean flour, chalk or alum. Alum is an aluminium-based compound, today used in detergent, but then it was used to make bread desirably whiter and heavier. Not only did such adulteration lead to problems of malnutrition, but alum produced bowel problems and constipation or chronic diarrhoea, which was often fatal for children.

A child dying of tuberculosis, a common Victorian ailment

2. Boracic acid in milk

Bread was not the only food being altered - tests on 20,000 milk samples in 1882 showed that a fifth had been adulterated - but much of this was done not by manufacturers but by householders themselves. Boracic acid was believed to "purify" milk, removing the sour taste and smell from milk that had gone off. Mrs Beeton told consumers that this was "quite a harmless addition", but she was wrong. Small amounts of boracic acid can cause nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea, but worse, it was what boracic acid concealed that was particularly dangerous. Before pasteurisation, milk very often contained bovine TB, which would flourish in the bacteria-friendly environment created by the substance. Bovine TB damages the internal organs and the bones of the spine, leading to severe spinal deformities. It is estimated that up to half a million children died from bovine TB from milk in the Victorian period.

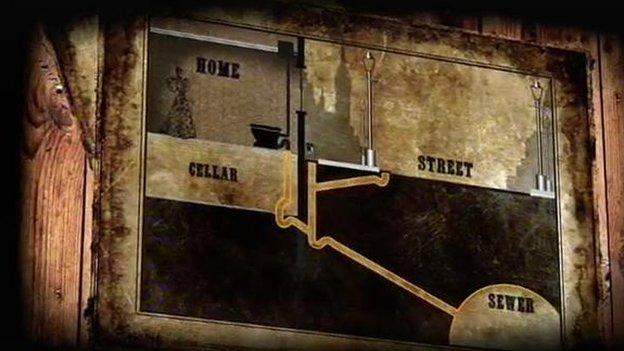

Early Victorian plumbing was prone to explosions as methane built up in the sewers

3. Dangerous bathrooms

The bathroom as we know it is a Victorian invention, but at first, it could be a dangerous place. Besides horrible cases of scalding in the bath, there are even reports that there were incidents of lavatories spontaneously exploding. The reason this might have been possible was that flammable gases such as methane and hydrogen sulphide, emanating from human waste, built up in the sewers and, in early toilets, could leak back into the home, where they could theoretically be ignited by the naked flame of a candle. Changes to toilets - beginning in the late 18th Century and continuing in the Victorian era - sorted the problem of gas leaking.

4. Killer staircases

As houses were thrown up rapidly, one area of design that was often overlooked was the staircase, especially those installed for the use of servants. Made too narrow and too steep, with irregular steps, the servants' staircase was a deadly construction. Add the weight of carrying trays or the complication of long skirts, and the stairs could easily prove fatal.

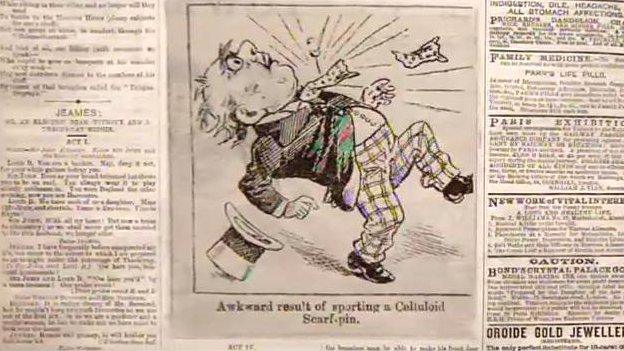

Celluloid was used to make corset frames, billiard balls and bow ties with occasionally disastrous consequences

5. Flammable parkesine

An oft-forgotten British inventor is Alexander Parkes, who invented the mouldable material that we today call plastic. He christened it parkesine but it quickly became known by its American name of celluloid. Such early plastics were highly desirable because they allowed everything from brooches and hair combs to billiard balls, previously only available in expensive ivory, to be made cheaply. It was even used to make collars and cuffs that could be easily cleaned. Unfortunately, parkesine is also highly flammable - as it degrades, it can self-ignite and is explosive on impact. Not ideal for a billiard ball.

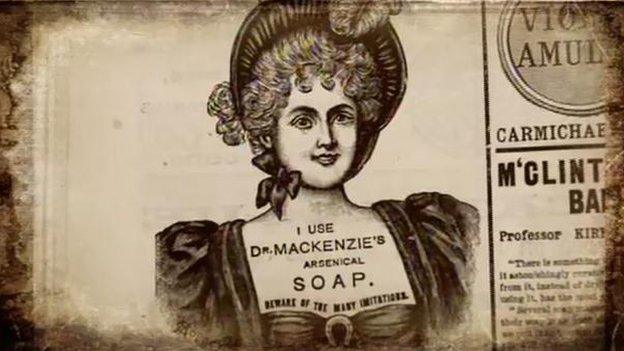

Arsenic and strychnine were commonly used in Victorian cleaning products

6. Carbolic acid poisoning

Victorians linked cleanliness to ideas of morality and respectability - the idea that it was next to Godliness was deeply ingrained. The new science of microbes only intensified the Victorian preoccupation with tackling germs, which they now knew could lurk out of sight. Chemical cleaning products to eradicate dirt and disease were heavily advertised and highly effective, but their toxic ingredients, like carbolic acid, were contained in bottles and packages that were indistinguishable from other household products. Boxes of caustic soda and baking powder could easily be mistaken. In September 1888, the Aberdeen Evening Express reported that 13 people had been poisoned by carbolic acid in one incident - five died. Only in 1902 did the Pharmacy Act make it illegal for bottles of dangerous chemicals to be similar in shape to ordinary liquids.

Radium was used in products such as makeup and condoms

7. Radium

A magical new element was discovered in the Edwardian era - a source of energy and brightness that delighted and fascinated the Edwardians - radium. It was used, like asbestos, in all manner of products, such as cigarettes, condoms, makeup, suppositories, toothpaste and even chocolate. Above all, there was a craze for glow-in-the-dark watch faces, which were painted by the "radium girls". Yet, as we now well know, radium is a source of radiation poisoning - if ingested, it could lead to anaemia, bone fractures, necrosis of the jaw, and leukaemia.

8. The wonder material

Edwardian engineers thought they'd discovered a wonder material- a mineral that was non-flammable, cheap and clean. It was used for just about everything in the early 20th Century home - hairdryers, floor tiles, toys, oven gloves, gutters, insulation, even clothing. However, the wonder material - asbestos - was, as we now know, deadly. Asbestos fibres can enter the lungs to devastating effect. We still don't know the full number of deaths that have resulted from it because it remains a lethal hazard.

9. Fridges

Domestic refrigerators began to enter the home in the Edwardian era. They were tremendously useful and exciting new goods, with which the consumer could demonstrate fashionable wealth, but their initial designs were fatally flawed. They leaked toxic gases such as ammonia, methyl chloride and sulphur dioxide, which damaged the respiratory system and could easily lead to death.

At first it was just lighting, but then electricity companies invented various products for the home

10. Electricity

The arrival of electricity was an extraordinary innovation. At first, people didn't know how to use it - warning signs advised them not to approach the electric socket with a match. In the early 20th Century, electricity companies sought to interest consumers in electric products beyond lighting. Some of these were obviously flawed - the electric tablecloth into which lamps could be directly plugged clearly didn't go well with a water spillage - but the real danger came from consumers trying to run many appliances from one socket, from trying to fix problems themselves and from un-insulated wires. The newspapers are full of cases of people electrocuting themselves.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

Correction: An earlier version of this story wrongly stated that Thomas Crapper's invention of the "siphon valve" tackled the problem of sewer gas leakage in toilets.