Cabinet papers reveal 'secret coal pits closure plan'

- Published

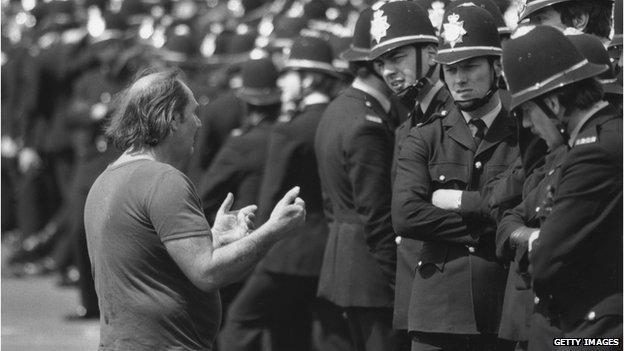

The miners' strike of 1984-85 was characterised by often violent confrontations with police

Newly released cabinet papers from 1984 reveal mineworkers' union leader Arthur Scargill may have been right to claim there was a "secret hit-list" of more than 70 pits marked for closure.

The government and National Coal Board said at the time they wanted to close 20. But the documents reveal a plan to shut 75 mines over three years.

A key adviser to then-PM Margaret Thatcher denies any cover-up claims.

The miners' strike began in March 1984 and did not end until the next year.

Other papers from 1984 reveal warnings of violence outside the Libyan embassy, in which WPC Yvonne Fletcher was killed.

One of the warnings was passed on by the British ambassador in Tripoli, Oliver Miles, who was sceptical about what he was told by Libyan government officials.

And the previously confidential files released on Friday by the National Archives also show the effect of the Brighton bomb on Mrs Thatcher's thinking about Ireland.

'Secret' meeting at No 10

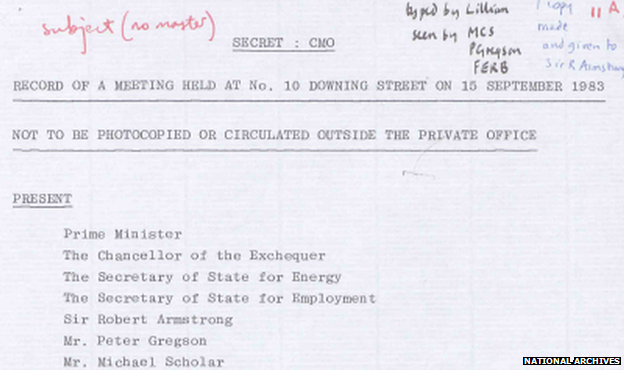

A document in the secret files includes an instruction that details of the meeting should not be made public

The year-long miners' strike, which started in March 1984, was characterised by often violent confrontations between police and massed picketing miners.

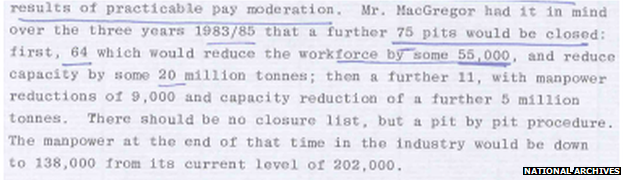

But one of the documents in the archives suggests that there was an agreement in government to shut 75 pits over three years, and cut 64,000 jobs - but that no list of which should be closed should be issued.

Nick Jones, who covered the strike for BBC radio as its industrial correspondent and later wrote a book about the dispute, said a document in the files dating from September 1983 was of particular significance.

The document, marked "Not to be photocopied or circulated outside the private office", records a meeting attended by just seven people, including the prime minister, chancellor, energy secretary and employment secretary, at No 10.

The meeting was told the National Coal Board's pit closure programme had "gone better this year than planned: there had been one pit closed every three weeks" and the workforce had shrunk by 10%.

The new chairman of the board, Ian MacGregor, now meant to go further.

"Mr MacGregor had it in mind over the three years 1983-85 that a further 75 pits would be closed... There should be no closure list, but a pit-by-pit procedure.

"The manpower at the end of that time in the industry would be down to 138,000 from its current level of 202,000."

The document reveals that plans for pit closures and subsequent job losses were discussed

As a result, two-thirds of Welsh miners would become redundant, a third of those in Scotland, almost half of those in north east England, half in South Yorkshire and almost half in the South Midlands. The entire Kent coalfield would close.

The final paragraph of the document read: "It was agreed that no record of this meeting should be circulated."

A week later another document written by a senior civil servant suggested the same small group should meet regularly in future, but that there should be "nothing in writing which clarifies the understandings about strategy which exist between Mr MacGregor and the secretary of state for energy".

The papers revealed the government briefly considered getting troops to move coal

"If this document had ever emerged during the strike it would have been devastating for the credibility of Margaret Thatcher" because Mrs Thatcher and Mr MacGregor always maintained there were plans for the closure of only 20 pits, said Mr Jones.

"It raises in my mind the question of whether there was a cover-up of these figures, and whether when we look back at what actually happened Arthur Scargill was right when he claimed that Ian MacGregor wanted to butcher the industry all along."

But it is a version of events that is pooh-poohed by Lord Armstrong, who as Sir Robert Armstrong was Mrs Thatcher's cabinet secretary at the time.

The National Coal Board was closing something like 20 pits a year anyway, he said - 75 over three years was not such a big increase. The real issue was Mr Scargill's "impossible demand" for a guarantee that uneconomic pits would not be closed.

So why the secrecy? "I think when you're in a negotiation of this kind you want to show as little of your hand as you can to those who are negotiating, particularly if the purposes of those people are, as they were in this case, malign," he told the BBC.

The prime minister was conscious of her public image - having her hair done 11 times a month on average

The papers reveal that in July 1984 - when the dock workers also went out on strike - the government briefly wobbled and considered calling a state of emergency and getting troops to move coal.

But it decided the risk of alienating crucial power station workers was too great. "The use of service drivers... would sharply increase the emotional temperature," ministers were warned.

In November of that year, two Home Office civil servants reviewed police tactics during the strike and found them sometimes wanting.

Alison Smith and her colleague Robert Hazell visited two police forces in the thick of the dispute - West Yorkshire and South Yorkshire.

They concluded that one of the most controversial tactics used by the police, stopping coach-loads of striking miners on their way to mass pickets and turning them back, may have been counter-productive.

"Turning them back may merely send them to other destinations to demonstrate, rather than deterring them from attending a picket line at all," they wrote.

And once they had been diverted the police might have no information on where they were.

Both police forces made use of outside manpower in the shape of "police support units", or PSUs, from other forces.

The civil servants found the most sought-after PSUs came from non-metropolitan police forces in the south of England - Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Avon and Somerset and West Mercia. But those from London could be a problem.

"Metropolitan PSUs were valued in violent confrontations but at other times... their attitudes were thought to be harder for local people to identify with and so perhaps more likely to lead to an increase in tension.

"The casual approach of the metropolitan PSUs had been a surprise to those forces which had not the same experience of public order problems being treated as everyday occurrences."

Violence warning at Libyan embassy

The papers reveal how it was Mrs Thatcher's decision to let the Libyans go

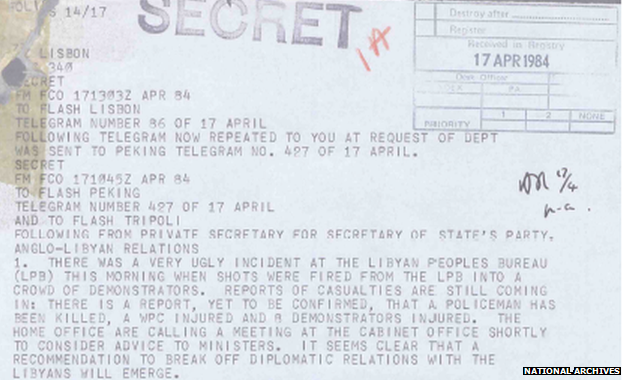

The files also contain details of three warnings received by the Foreign Office of possible violence at the demonstration outside the Libyan embassy - known as the Libyan people's bureau - on the morning of 17 April 1984.

On that morning WPC Fletcher died and 11 people were injured when a machine-gun was fired into a crowd of anti-Gaddafi demonstrators from the windows of the bureau in St James's Square in central London.

The first warning came from a pair of Libyan diplomats who rang the Foreign Office and then went there in person just after midnight, and again on the morning of the shooting.

A telegram later that day to Foreign Secretary Sir Geoffrey Howe, who was in Beijing, described the shooting as "a very ugly incident" and said the diplomats' request had been passed on to the Home Office and the police during the night, "drawing attention to the fact that the Libyans were capable of carrying out their threats".

The telegram said Special Branch decided nonetheless to allow the demonstration to go ahead. "A substantial police presence was arranged and barriers were installed to control the crowd," it said.

The telegram to the foreign secretary about the shooting outside the Libyan embassy

A second warning came when Mr Miles was summoned to a meeting at the Libyan foreign ministry, again after midnight.

In a telegram to London sent early the next day he reported what a Libyan official had said: "The Libyan government would not be responsible for the consequences if the demonstration took place and they might include violence."

He replied that threats of violence did not impress the British government.

His telegram went on: "I was shown out by the UK desk officer who seemed as little impressed by this performance as I was. I made a bet with him that no such demonstration will take place. Grateful to know the outcome."

Mr Miles has long since retired but denied he had not taken the warning seriously. "I did take it seriously, which was why I passed it on to the Foreign Office," he said. "But I didn't believe it, no."

Sir Geoffrey later told the Commons: "The House should know that such night-time summonses were by no means unusual in Tripoli."

The third warning came from GCHQ, which intercepted a message from Tripoli instructing those in the Bureau to open fire - but the intercepts only arrived three hours after WPC Fletcher was shot.

The following day Mrs Thatcher, who was on an official visit to Lisbon, accepted that the policewoman's murderer would have to go free in order to protect British diplomats and citizens in Libya, even if the public were outraged.

The Libyans enjoyed diplomatic immunity and the police could not arrest them or enter their bureau. A police request to search the bureau would, she was told, "set a very dangerous precedent" and would invite retaliation in Tripoli.

There is a note of a phone conversation between Mrs Thatcher and home secretary Leon Brittan in London.

"The home secretary asked whether repatriating the Libyan staff, including the perpetrator of the murder, could be defended.

"The prime minister thought it could, provided British staff were successfully repatriated too."

In a later discussion, the pair also agreed that Britain would have to turn a blind eye if the Libyans used diplomatic bags to smuggle weapons out of the bureau.

In the event, while police in London besieged the Libyan people's bureau for a total of 11 days, the British embassy in Tripoli was also surrounded. Mr Miles cabled on 17 April: "My staff and I are being prevented from leaving the embassy by a group of revolutionaries who are issuing orders to the police."

And on 24 April the ambassador reported that the Libyans were threatening ("via Willey of the BBC") to enter and burn his embassy if police in London entered the Libyan bureau.

There were several days of tense negotiations before women and children from the embassy were allowed to leave Libya. The rest of the diplomats followed as Britain and Libya broke off diplomatic relations (they were not restored until 1999).

Meanwhile, the Libyans in London finally left their bureau on 27 April and were taken to the Civil Service College at Sunningdale to be questioned by police before being put on a plane at Heathrow.

Parliament was later told that police had narrowed down the identity of the murderer to one of two people, but that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute.

A list in the files of the 30 people taken from the bureau included one man named as the shooter in 2011 by a Canadian prosecutor working on behalf of Scotland Yard.

Thatcher 'gratuitously offensive' to Ireland

The bomb blast at Brighton's Grand Hotel left five people dead and more than 30 injured

The newly-released files also show the effect of the Brighton bomb of 12 October 1984 - which targeted the Conservative conference hotel in the town, killing five and injuring many others - on Mrs Thatcher's thinking about Ireland.

She had been due to meet Irish leader Garret FitzGerald at a summit a month after her party conference to discuss an Anglo-Irish agreement (eventually signed in November 1985, and seen as the first step in the process that led to the Good Friday agreement of 1998).

Secret talks had been going on for many months between Sir Robert Armstrong and his opposite number in Dublin, Dermot Nally, aimed at forging an agreement.

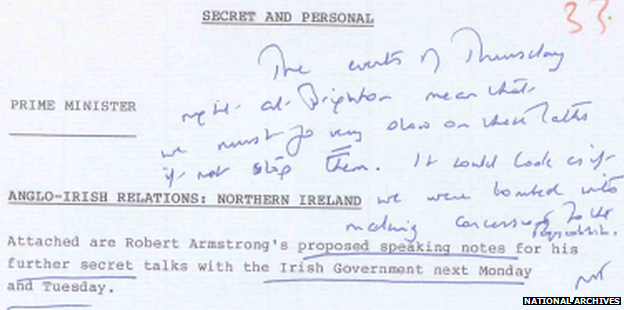

But on a background briefing for the summit the prime minister wrote: "The events of Thursday night at Brighton mean that we must go very slow on these talks if not stop them. It would look as if we were bombed into making concessions to the Republic."

Margaret Thatcher's note written in blue pen on the summit briefing document

In the event a meeting on 31 October decided to continue the Armstrong/Nally talks.

Foreign secretary Sir Geoffrey told his colleagues: "There was no question of the government being bombed into concessions. But nor should they be bombed out of a search for a settlement."

Mrs Thatcher's sympathies for Northern Ireland's unionists also made agreement difficult.

She rejected an early draft of a communique to be issued after the summit, writing at the top of the document: "I could not possibly agree to this. It would strike fear into the unionists."

Beside the proposed form of words - "There can be no change in the constitutional status of Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom without the consent of the majority of its people" - she wrote "Not strong enough" and offered an alternative: "The province is part of the UK and will remain so unless the majority etc."

At the summit itself, in a private meeting with no civil servants present, the two leaders shared their fears that if the peace process did not move forward the moderate nationalist SDLP would lose ground to Sinn Fein. Mr FitzGerald said that might lead to civil war.

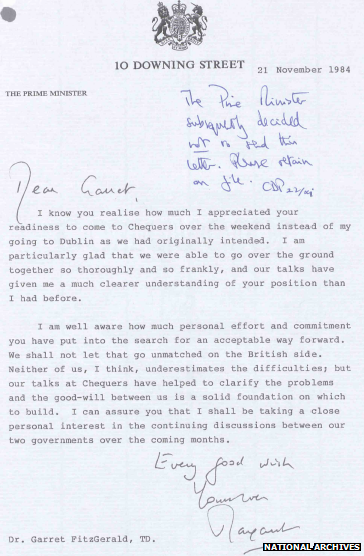

A letter written by Margaret Thatcher to then Irish leader Garret FitzGerald that was never sent

Mrs Thatcher told him the IRA had a Marxist and an international terrorist dimension to it.

"She was beginning to understand what the United States felt about Nicaragua," she added.

After the summit she caused a diplomatic incident when she robustly rejected at a press conference three possible models for the future of Northern Ireland - unification with the Republic, confederation or joint British-Irish rule.

This caused a furore in Ireland, and Mr FitzGerald privately called her remarks "gratuitously offensive".

His words were leaked - one consequence was that Mrs Thatcher decided not to send him a personal letter thanking him for coming to the summit.

"Neither of us, I think, underestimates the difficulties; but our talks at Chequers have helped to clarify the problems and the good-will between us is a solid foundation on which to build," she wrote.

The letter was signed: "Every good wish, yours ever, Margaret."

At the top of the letter one of her senior advisers, Charles Powell, wrote: "The prime minister subsequently decided not to send this letter. Please retain on file."

Update 13 February 2014: Chris Collins of the Margaret Thatcher Foundation has written to me complaining that the target of more than 70 pit closures only ever represented the "preliminary conclusions" of the Coal Board chairman Ian MacGregor, and - on the evidence of the documents quoted - was never adopted as government policy.

He and I agree that in September 1983 ministers were told at a meeting about MacGregor's plan to close 64 pits, rising to 75 over three years. I argue this plan was "secret", as evidenced by the decision not to circulate a written record of the meeting and by a note of 21 September from Mrs Thatcher's private secretary which says there is to be nothing in writing clarifying the understandings between MacGregor and ministers.

But what happened after that? At a meeting on 19 January 1984 ministers explicitly adopted a plan to cut jobs by 45,000 over two years (and thus close 45 pits). Nothing was said about any further closures. "Summing up," we are told, "the Prime Minister said that the objective of a more accelerated run-down of coal capacity was accepted." Nick Jones argues this implies support for the longer-term objective of achieving NCB break-even by 1988, which MacGregor believed meant closing up to 75 pits.

There is in the documents no explicit statement adopting the 75 pit target as government policy (though given the sensitivity about putting anything in writing you would not expect one). Equally, there is no explicit statement disavowing the target.

- Published1 August 2013

- Published1 August 2013