Sentencing: Who's soft?

- Published

- comments

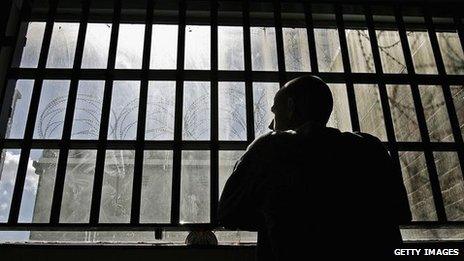

Figures show that more people are going to jail for longer

It is the moment that the convicted criminal cares about most: how long are they going to get?

But while some may tremble (or just occasionally sneer) in the dock, what politicians care about is how many of them are actually locked away.

Today Labour made a big deal of some Ministry of Justice figures they unearthed which relate to the sentencing of some more serious criminals.

They say that around half of criminals convicted of sex offences, violence and burglaries in England and Wales in 2012 were not sent to prison.

Those figures are attention grabbing - but they need to be placed firmly in an important recent historical context before anyone can make any sense of what they mean.

So let's start with some basic facts about the prison population.

It is popularly believed that - back in the days when the world was black and white - Britain's prisons were packed with criminals, and that since then the country has gone soft.

Well, in 1945 there were roughly 15,000 people in jail. Today, the figure stands at 83,000 - and that huge leap isn't because we stopped sending people to the gallows.

The prison population has climbed because both Labour and Conservative governments have introduced laws that have led, incrementally, to more people being jailed - and more of them for longer.

There are inevitably fluctuations, but broadly speaking the prison population has doubled since 1993 thanks to Parliament telling judges to hand out longer jail sentences.

That trend began under John Major, continued under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown - and continues today under David Cameron and Nick Clegg's coalition.

The detail on specific offences reveals a little more about what has been going on - but again it has to be placed in context.

Over the last decade the rate of sex offenders being jailed has fluctuated - but not by very much.

In 2003, six out of 10 sex offenders were immediately sent to jail. During the later Labour years the figure dropped slightly, before today reaching around the same level again.

Official figures show that the number of sex offenders in jail has been increasing faster than other types of prisoner - and the sentences they have been receiving have also been increasing.

Ten years ago the average sentence given to a sex offender was just short of 40 months. Now it's more than 55 months - and that does not include the number given life or other forms of indeterminate sentence.

Cautions for sex offenders have also risen, but this is a more complex story.

Government figures show that almost a third of those who receive a caution are boys aged between 10 and 17. An official study in 2011 also suggested that the most common crime for which a caution was given was an assault on a female involving touching in a sexual manner without consent.

The Justice Secretary Chris Grayling has already said he is restricting the use of cautions by banning their use for adults who commit serious crimes, including sex offences, or the same crime twice in two years.

So we can see that over the decades, the sentencing regime has got tougher - and ministers are now telling people to stop using cautions.

That leaves one final question: are judges soft?

The answer is highly subjective - but on Tuesday, Dominic Grieve QC, the Attorney General, provided MPs with important figures on the number of sentences for serious offences that are reviewed for being too short.

Anyone can complain to his office that a serious criminal was given an "unduly lenient sentence" - and if he agrees that there is a case to look at, he sends it up to the country's top judges at the Court of Appeal for reconsideration.

His office receives about 450 referral requests a year - and he asked the Court of Appeal to look at 67 cases last year.

One of the most well-known was the case of the former BBC commentator Stuart Hall - his sentence for sex offences was doubled.

But that dramatic example aside, the 67 referrals make up a minuscule proportion of the number of convictions made every year. And on that basis, it is very hard to argue that judges aren't in line with either politicians or the public, who both want to see serious offenders jailed.