Coming out: 'I went to work expecting the worst day of my life'

- Published

A table of the most gay-friendly employers has been published by campaign group Stonewall, external. But what reaction can people in traditionally macho jobs expect from colleagues after they come out?

On paper it was a perfect afternoon.

Wales were minutes away from a rare Six Nations win over England.

Watching in a London pub, James Wharton - an 18-year-old soldier from Wrexham - should have been revelling in the victory in front of his four English friends.

"I should have been jubilant," he remembers. "I'm normally quite a loud character with my mates but I was in my box, I was depressed."

One-by-one they asked him what was wrong: "Is it debt? Problems back home?"

Then, as at least one of them already suspected, "Are you gay?"

James Wharton served for seven months in southern Iraq as an armoured reconnaissance soldier

He was about to admit to them what he had so far admitted only to himself.

"I never set out to come out. It just sort of happened."

That, it turned out, was the easy part.

As James puts it: "I knew I had to go back to work and that it wouldn't be four friends I was telling. It'd be 200 people who I didn't really know."

A ban on gay men and women serving in the armed forces had been lifted only five years earlier, external.

His superiors called him in.

Before 2000 it would have been a court martial offence, his room would have been turned over for evidence and his fledgling army career would have been over.

Left in hospital

But instead they offered support. They asked if everything was OK or if he needed time to tell his parents.

"I went to work expecting the worst day of my life," he remembers.

"But I guessed it wrong. What I anticipated didn't come to pass."

His comrades treated him as though he were a minor celebrity.

And when he was deployed to Basra, he kept a photo of his partner by his bed.

Only once or twice did the bullying he had been braced for go beyond what he calls "the obvious banter".

James and his partner Tom entered into a civil partnership in 2010.

Most of the time his friends stepped in, but on one occasion - just months after coming out - a vicious homophobic attack left him in hospital.

He had been drinking in a bar with a fellow soldier.

But later that night, when he took him back to the barracks: "Instead of what I assumed was going to happen, I got beaten up."

The other soldier would later face a court martial.

He had beaten James with an iron pole, kicking and punching him, leaving him bloodied in his room.

It was a brutal but one-off incident and in the decade James spent in the Army, he says the atmosphere became markedly less homophobic.

'Wrong'

Before that, the casual and at the time legal discrimination meant soldiers had to live a lie or keep their true self well-hidden.

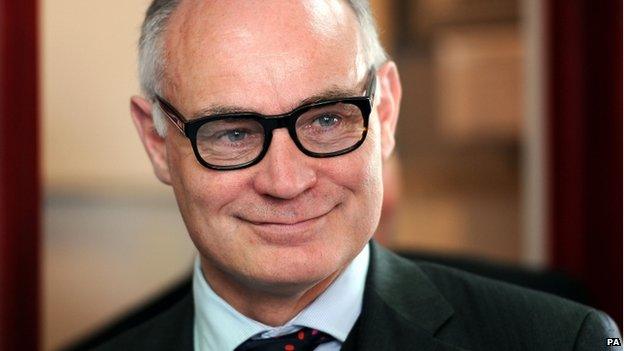

It was under these conditions that MP Crispin Blunt - until recently prisons minister in the coalition government - spent 11 years as a soldier, rising to the rank of captain and never admitting he was gay.

"Even if my instinct was in that direction, it was illegal; it was wrong," he says now.

"I was a soldier's son. Both my grandfathers were in the forces. I had absolutely no contact with what you might call 'gay society'.

"These were people to be laughed at."

Before he became an MP, Crispin Blunt spent the 1980s in the Army.

In the 1990s he left the forces, started a family and swapped the battlefield for the benches of the House of Commons - another male-dominated, often bruising place where any perceived weakness can be mercilessly exploited by rivals and opponents.

Then, in summer 2010, his marriage of 20 years came to an end.

He had taken the decision to come out and had to explain why he was no longer appearing in public with his wife.

After putting out a press statement and emailing his local Conservative Association, he returned to the Commons not knowing what to expect.

Mr Blunt has been MP for Reigate since 1997

"Members kept coming up to me and asking 'are you OK?'" he says.

"I wanted to say I'm more than OK.

"You think it's going to be absolutely dreadful and in fact it's a positive experience - the euphoria of finally being able to be yourself."

'Destroying lives'

And despite Parliament's image as boisterous and sometimes boorish, he says it was the atmosphere at Westminster - in contrast to his time in the Army - that encouraged him to come out.

It would now be close to "career suicide", he says, to criticise a fellow MP because of their sexuality.

Just a few years earlier the climate for politicians and those in public life was very different.

After a number of ministers in the then Labour government came out in 1998, the Sun newspaper splashed across its front page: "Are we being run by a gay mafia?"

But, as Crispin Blunt puts it, "society was changing".

The paper misjudged the public mood and apologised, external, promising it was "no longer in the business of destroying closet gays' lives".

'Sex romp'

On the receiving end of the Sun's sister paper, the now-defunct News of the World, was retired police officer and trainer Vic Codling.

It was 1991 and the 6ft-plus, broad-chested Geordie was standing before the new intake of police recruits at the Met's training base in north London explaining how to make an arrest.

"The boss wants to see you," came a message.

He was called into the superintendent's office.

"Guess who I've just had on the phone," Vic's super asked.

It was the News of the World, demanding to know what he was going to do about one of his officers being involved in a "gay sex romp".

The former sheet metal worker had moved from the North East in part to escape homophobia - "an engineering site on Tyneside wasn't the sort of place you wanted to be a 'poof'," he says.

And now he was about to be outed - not just to his boss, colleagues and the rookie officers but to the world.

'Disgraceful'

When the kiss-and-tell was published under the headline "Gay cop took down my particulars", he recalls the reaction of politicians and retired policemen.

"They said, 'what on earth is this practising homosexual man doing working with young officers?'."

But from the rank-and-file and, for the sake of his career, his superiors?

"I never had a single negative reaction.

"It shouldn't have surprised us," he says, echoing soldier James Wharton and MP Crispin Blunt.

"I thought the overall reception was going to be terrible. But it wasn't."

When confronted with the tabloid expose, he denied the "romp" but confessed his sexuality.

"Who cares?" was his superintendent's response.

Until 2003 police officers were barred from marching in uniform at London's Gay Pride

Vic, now national co-ordinator of the Gay Police Association, says he wouldn't have dreamed of going to his reps at the Police Federation.

"They'd said it was disgraceful that a gay officer was involved in training."

He says it was and still is harder for police officers in smaller, rural communities where coming out at work effectively means coming out to everyone - family, friends, and the public being policed.

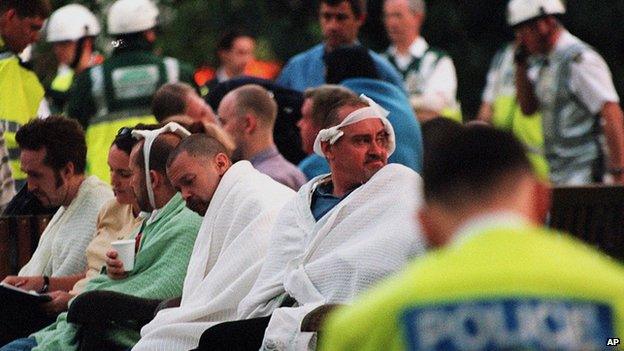

But huge strides had been made, in part because of a homophobic bomb attack on a gay pub in Soho which killed three people and left dozens injured.

The aftermath of the Admiral Duncan bombing

The Met needed officers who understood the gay community. They travelled from around the country - Cumbria, Scotland, Northamptonshire, Northumbria.

"People came out as gay to help the investigation," Vic says.

"If you wanted to go to London you had to explain why."

He believes the way he had been outed though, in such a public way, did his career no harm at all.

Issues of homophobia in the police were pushed his way. He got support from unexpected places.

"Suddenly, because my profile had been raised, people found it easier to come forward."

But despite the progress, Vic believes the force, and many workplaces in Britain, remain "institutionally heterocentric".

"People keep talking about tolerance. We don't want to be tolerated - we want to be accepted."

- Attribution

- Published15 January 2014