Obituary: George Blake

- Published

George Blake, shown in 2001, had lived in Moscow since the 1960s

George Blake's escape from Wormwood Scrubs prison in London in 1966 was a major embarrassment to the government of Harold Wilson.

Blake, convicted of betraying British MI6 agents to the Soviet Union, had completed just five years of a 42-year sentence.

His escape was arranged by three former inmates, including two peace campaigners, and financed by the film director Tony Richardson.

With the help of friends he was hidden in safe houses before managing to escape to the Soviet Union, where he spent the rest of his life.

Blake was born George Behar on 11 November 1922 in the Dutch city of Rotterdam.

His father was a Spanish Jew who had fought with the British army during World War I and acquired British citizenship.

At the age of 13 Blake was sent to Cairo where he stayed with his father's sister, who was married to a wealthy banker.

There he became close to one of his cousins, a committed communist who, Blake remembered, had a great influence on him.

Blake claimed the US bombing of North Korea persuaded him to change sides

He returned to the Netherlands in the summer of 1939 and was staying with his grandmother in Rotterdam when the Germans invaded the following spring.

His mother and sister were evacuated to England but Blake remained, and as a British citizen was temporarily interned by the Germans.

When it became clear the proposed German invasion of England would not take place, Blake managed to get hold of forged papers and joined the Dutch resistance.

"Although I was 18," he later recalled, "I looked much younger and therefore was very suitable to act as a courier."

Fluent

Over the next two years Blake carried messages between Dutch resistance groups but eventually decided to try to reach England and join the armed forces.

He travelled down to neutral Spain where, after being imprisoned for three months, he managed to reach England via Gibraltar.

He joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve where he was asked, because of his background, if he would like to work in intelligence.

Blake returned home from North Korea in 1953 as a hero

He was fluent in Dutch and was deployed to decipher coded messages sent to London by the Dutch resistance.

When the war ended, he was posted to Germany where he spied on the Soviet forces occupying what was then East Germany.

He was so successful it was decided to return him to England where he learned Russian at Cambridge.

Blake later said: "In a way it shaped another stage in my development towards communism, towards my desire to work for the Soviet Union."

Bombing

He was transferred to South Korea just before the outbreak of war between the western-backed South and Soviet-backed North.

His job was to set up a network of agents to spy on the North but poor communications made his task difficult.

When the North captured the city of Seoul, Blake found himself interned along with a number of diplomats and missionaries.

He later denied claims that he had been brainwashed into working for the Soviet Union.

It was in Berlin that Blake handed his information to the Soviets

Blake said it was the continual bombing of small villages by American planes that made him feel ashamed of the actions of the West.

He was also influenced by a copy of Karl Marx's book, Das Kapital, which had been sent to the prisoners by the Soviet embassy.

Blake commented later: "I felt it better for humanity if the communist system prevailed, that it would put an end to war."

In the end Blake simply wrote a note to the Soviet embassy offering his services. It resulted in an interview with a KGB officer.

Betrayal

By the time Blake arrived back in England after his release in 1953 he was a fully fledged Soviet agent.

In 1955 he was sent to Berlin where he was given the task of recruiting Soviet officers as double agents.

It was the ideal role for the man who was now committed to the Soviet Union.

Much in the manner of Bill Haydon, in John le Carre's Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, Blake passed British intelligence to his Soviet handlers while pretending the flow was the other way.

Blake's escape from Wormwood Scrubs was a huge embarrassment to the British authorities

Over a period of nine years, Blake handed over information that led to the betrayal of some 40 MI6 agents in Eastern Europe, severely damaging British Intelligence.

He said later: "I don't know what I handed over because it was so much."

His downfall came when a Polish secret service officer, Michael Goleniewski, defected to the West, bringing his mistress and details of a Soviet mole in British intelligence.

Blake was recalled to London and arrested. At a subsequent trial he pleaded guilty to five counts of passing information to the Soviet Union.

Hero

Based on the sentences given to other spies arrested at the time, Blake was expecting a 14-year term.

But instead he was sentenced to 14 years on each of three counts; the 42-year term was then the longest ever imposed in a British court other than life sentences.

"As a result," Blake later recalled, "I found a lot of people who were willing to help me for the reason they thought it was inhuman."

His escape was helped by the lax conditions in the prison and his warders' assumption that he was resigned to his sentence.

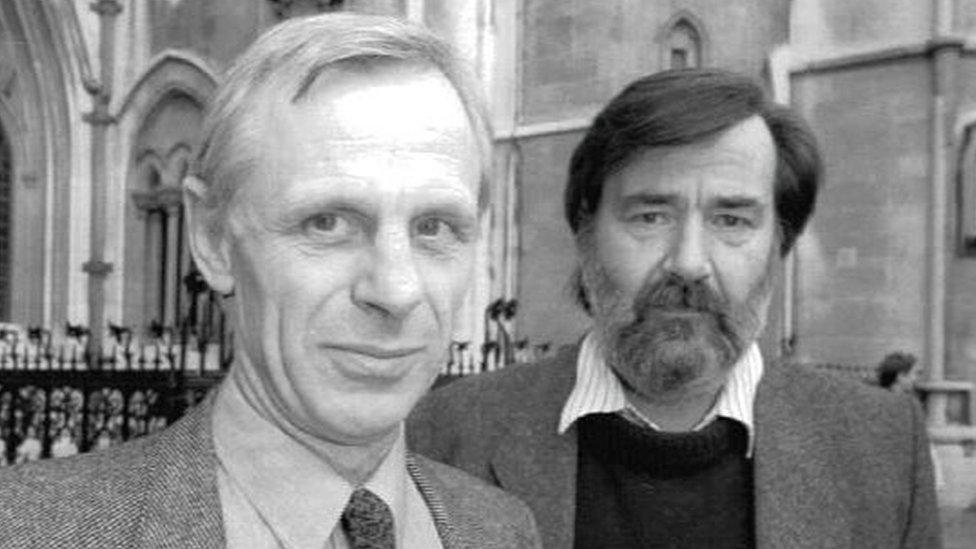

Peace campaigners Michael Randle (l) and Patrick Pottle were responsible for aiding Blake's escape

While in Wormwood Scrubs he met Sean Bourke, an Irish-born petty criminal.

On his release Bourke, together with two anti-nuclear campaigners, Michael Randle and Pat Pottle, helped Blake scale the prison wall.

In the process Blake fell and fractured his wrist but managed to get into a waiting van. After a period of hiding in various houses, he was smuggled to East Germany in a camper van and then to the Soviet Union.

No regrets

Feted as a hero, he was made a KGB colonel and given a pension, an apartment in Moscow and the Order of Friendship by Vladimir Putin.

Blake was that most dangerous of traitors: a man who acted because of principle rather than for reward.

He never had regrets and remained a committed Marxist-Leninist.

Like many intellectuals of his time, including Kim Philby, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, he came to despise the British social system and worked for its downfall.

"To betray, you first have to belong. I never belonged," he said.

Unlike them, Blake lived to see the end of the communist regime in Russia, an ideal for which he had betrayed his country and his colleagues.

"I've enjoyed the happiest years of my life in Russia," he said in an interview to mark his 90th birthday.

"When I lived in the West I always had the risk of exposure hanging over me. Here, I feel free."

And in a statement in November 2017 he again praised the work of Russian spies.

They "have the difficult and critical mission" of saving the world, he said, "in a situation where the danger of nuclear war and the resulting self-destruction of humankind have been put on the agenda by irresponsible politicians. It is a true battle between good and evil."