Government to review young deaths in custody

- Published

Campaigners said there were many common themes linked to the deaths of young people in custody

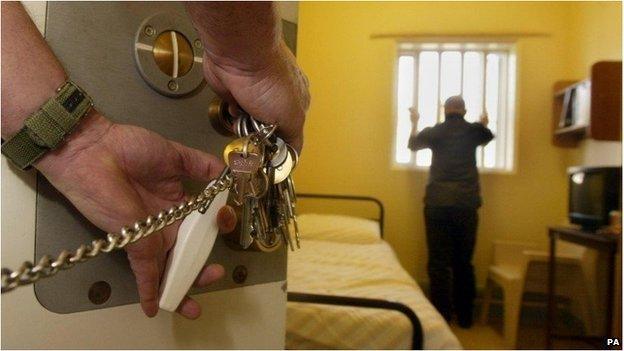

The government is setting up an independent review to investigate self-inflicted deaths in custody of people aged 18-24.

Justice Secretary Chris Grayling said the government was committed to the safety of offenders and to reducing the number of people dying in custody.

He said lessons learned from the review would benefit all age groups.

In the past 10 years, 163 children and young people under the age of 24 have died in prison.

Mr Grayling said: "Although there are already comprehensive investigations into individual deaths we recognise there is benefit at this time in collating lessons that may be system-wide."

He said the review would make recommendations for cutting the risk of future deaths.

The review will be led by the Labour peer Lord Harris of Haringey, who is chairman of the Independent Advisory Council on Deaths in Custody.

No under-18s

Justice Minister Lord Faulks told the House of Lords that the review would start "as soon as resources were in place".

He said the government wanted it to report back by spring 2015.

"It does not mean that lessons are not continuously learned from all other sources that provide information," he said.

"The review will focus on key themes including vulnerability information sharing and the safety of young people."

The former chief inspector of prisons, Lord Ramsbotham, said he regretted that the review covered only those aged 18-24 and not those under 18 as well.

He said the government's plans to build secure colleges for under-18s and its policy of putting all over-18s in adult prisons could "exacerbate existing flaws and create significant risk to young lives".

'Relentless'

Campaigners had pressed the government to set up an inquiry, arguing that doing so could address systemic failings in a way that individual inquests could not.

Justice Minister Jeremy Wright initially rejected the calls but later agreed to reconsider.

The charity Inquest, which was among those calling for an independent review, said that of the three under-18s who had died in prison since 2011, two were being monitored for suicide and self-harm at the time of their deaths.

In the same period, 41 people aged 18-24 died in prison from self-inflicted causes.

Inquest said 14 of these people, accounting for more than a third of the total, were being monitored for suicide and self-harm when they died.

Common features among children and young people who have died in prison from self-inflicted causes are diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), special educational needs, and personality and other disorders.

Before the decision to establish a review was announced, Deborah Coles, co-director of Inquest, said: "The state has frequently been put on notice about the scandal of deaths of children and young people in custody and yet has failed to act.

"The relentless nature of these deaths is shocking enough but the recurrence of depressingly familiar failings year after year should give most cause for alarm.

"Investigations and inquests are held in isolation, limited in remit and cannot address the wider systemic failures in state care both within and outside prisons."

'Fortified schools'

Speaking to BBC News before the review was announced on Thursday, Lisa Courtney - whose son Ben was 18 when he hanged himself at Portland Young Offenders Institution - said more light should be thrown on failures by such institutions.

Her son suffered from learning difficulties and ADHD, but she said his medical notes were never sent to Portland.

"Prisons are about punishment but they are not only about punishment," she said. "They are about correction.

"Ben was neglected, Ben was just left in a cell to die, left in a cell to hang himself.

"Something is going wrong in there."

Campaigners argue that the number of children and young people dying in custody means that the state is failing in its obligation to protect life under Article 2 of the Human Rights Act.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Justice has announced plans to spend £85m building a secure college in Leicestershire that will hold up to 320 young people in custody.

This is planned to be the first step towards several other "fortified schools" that will eventually cater for the vast majority of young offenders.

- Published17 January 2014

- Published10 July 2013

- Published1 May 2013

- Published14 March 2013

- Published6 March 2013