A huge challenge for the head of the Met

- Published

- comments

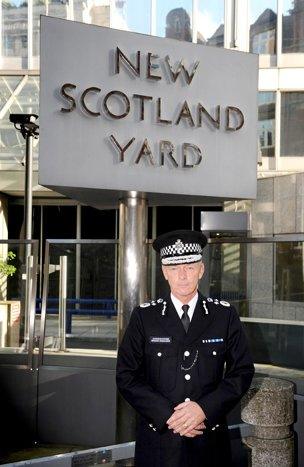

Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe

Two contrasting views have filled my Twitter stream in the last 24 hours.

One suggests that there is nothing remotely shocking about the review into police corruption, external and spying by the Met surrounding the Stephen Lawrence case - we all know the score.

The other view suggests that there is far too much being made of the activities of a very small handful of corrupt officers, and we must stress how the vast majority of the police service do an amazing job, day in and day out.

The shock of the review, for me, is that it suggests there was - and still is - a culture inside the Metropolitan Police which sees protecting the reputation of the Yard as more important than candour and transparency.

By way of example, the review says it was told only last month that certain material relating to the corrupt former detective John Davidson could not be found. "We have some reservations about accepting this assertion," the review states.

This is an elegant way of saying "we think the cops may still be lying".

The review also says "there must be serious concerns that further relevant material has not been revealed" by the Met. In other words, "we can't be sure that the police aren't still covering up evidence of corruption."

This is not some historical case concerning corruption by a small number of officers decades ago. This is about an organisation that a government-commissioned review still cannot trust to tell the whole truth.

So where was Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, the Metropolitan Police commissioner, yesterday? I am told he only received the review document yesterday morning and needed time to digest its contents.

That's why he sent one of his deputies out to dead-bat the media's questions. Today, Sir Bernard has told London's Evening Standard, external that yesterday was "one of the worst days that I have seen as a police officer".

He will be conducting a series of media interviews this afternoon, stressing his determination to restore trust and confidence in the Metropolitan Police.

His problem, though, is that some see him as part of the problem, not the solution.

The review is clearly not persuaded that Sir Bernard is taking the issue seriously enough. Asked in 2012 for material relating to an anti-corruption investigation conducted in the 1990s - Operation Othona - it took police a year to find a cardboard box containing a hard drive with some details of it.

Only then did it also emerge that every single hard copy of the investigation's findings were destroyed in a "mass shredding" in 2003.

Last summer the review asked about information relating to another corruption investigation and was told the material had not been indexed. When they asked again last December, they were told the material had still not been indexed.

These are matters which fall on Sir Bernard's watch. He will need to work very hard to shift any impression that he is reluctant to expose the skeletons in Scotland Yard's cupboards.

Trust in the police is vital. We know there is a strong link between confidence in police and the likelihood that citizens will obey the law. At the moment, public satisfaction and trust remains stable - roughly two thirds of people still think officers tell the truth.

But this is a time of reckoning for Scotland Yard. Sir Bernard has a huge task ahead of him.