Police forces 'may be overusing data gathering powers'

- Published

Police and other law enforcement bodies, such as the National Crime Agency, made the vast majority of the data requests

Police may be overusing their power to gather people's communications data, the Commissioner for Interception says.

In 2013, there were 514,608 requests, external - such as who owns a phone and who have they called - which Sir Anthony May said "has the feel of being too many".

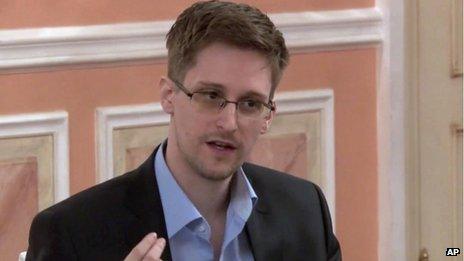

But he clears UK intelligence agency GCHQ of breaking the law or any rules - an accusation levelled by US whistleblower Edward Snowden.

The home secretary said his report showed agencies were acting lawfully.

Sir Anthony said there was a need to investigate whether the desire by police and law enforcement to access data was being prioritised over people's privacy.

The conclusions are contained in his first annual report in his new role, which looks at data requests made in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Prime Minister David Cameron said it showed "that public authorities do not engage in indiscriminate random mass intrusion".

Edward Snowden is an ex-employee of the CIA and former contractor for the US National Security Agency

One strand is "interception", when a warrant is issued for the full content of someone's communications to be listened into.

In this case there were 2,760 warrants in 2013 - a drop of 13% from the previous year. This was carried out by nine different agencies and resulted in 57 errors.

The second area is communications data - a much broader category.

This involves address and subscriber information relating to phone calls, such as what other numbers a phone was in contact with (but not what was said), who owns a phone and similar details about emails and computer IP addresses.

This is used much more broadly. In 2013, there were 514,608 requests (a drop from 2012, when there were 570,135). More than half were for subscriber information.

Police and other law enforcement bodies, such as the National Crime Agency, are the overwhelming consumers of this, accounting for 87.5% of requests.

A further 11.5% came from intelligence agencies (overwhelmingly from MI5, with 56,918 requests). Local authorities made up 0.3% and other bodies 0.5%.

Serious errors

In past years, there have been concerns over whether some bodies might be using these powers for areas not originally intended under the law - but the report says that less than half a per cent of requests were for purposes other than prevention and detection of crime or disorder, national security or preventing death or injury.

However, the commissioner does query whether there is too much reliance on this power, saying 514,608 requests is "a very large number".

He told the BBC: "It really does require to be investigated whether there may not be an institutional over-emphasis in police forces on progressing their criminal investigations and an institutional under-emphasis on the privacy side of it."

There were 970 errors - some of which were serious. For instance, when the police were trying to attend someone who might be attempting suicide or might be a victim of crime and went to the wrong address initially based on the communications data.

In two cases, warrants were executed at the homes of innocent people.

It is also clear that certain police forces use the power much more than others proportionate to their population.

Similarly, although the overall volume is much lower, there are wide variations in use by councils, with 121 not using it at all and others, such as Southampton, York and Birmingham city councils and the London boroughs of Bromley and Enfield, using it 80 or more times.

Foreign traffic

But on the issue of whether there is mass surveillance - a claim made on the basis of documents provided by US whistleblower Edward Snowden - the commissioner essentially gives Britain, and particularly GCHQ, a clean bill of health.

"I can assure anyone who is not associated with terrorists or serious criminals that the agencies have no interest whatever in examining their private communications and for practical purposes do not do so," he said.

Sir Anthony says he has found no evidence that GCHQ is circumventing UK law by getting material from the US

Sir Anthony acknowledged there were legitimate concerns that need to addressed, but said he believed the current legal framework - the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 - was broadly fit for purpose and being used correctly.

He found that even though so-called "general warrants" provide for large-scale collection of material, this was primarily focused on foreign traffic, and GCHQ could not indiscriminately trawl through it.

As a result, he said, there was no "sentient" intrusion into the private affairs of UK citizens - in others words, by a person rather than in automated fashion by a computer.

He also said he had found no evidence that GCHQ was circumventing the law by getting material from the US that it did not have the power to access itself.

Home Secretary Theresa May said the report "makes clear the intelligence agencies, law enforcement agencies and other public authorities operate lawfully, conscientiously and in the national interest".

Foreign Secretary William Hague, the minister responsible for GCHQ, said: "A senior and fully independent judge has looked in detail at whether the interception agencies 'misuse their powers to engage in random mass intrusion into the private affairs of law abiding UK citizens'.

"He has concluded that the answer is 'emphatically no'.

"We are open to suggestions to strengthen the oversight framework even further and make it as transparent as possible without putting security at risk."

- Published17 January 2014

- Published21 November 2013

- Published18 July 2013