Max Clifford: How PR guru tried to spin his own trial

- Published

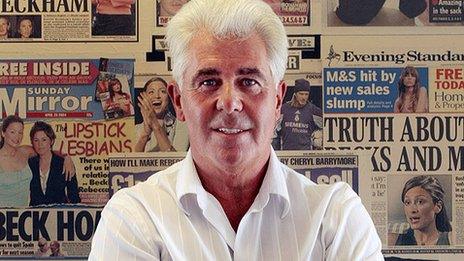

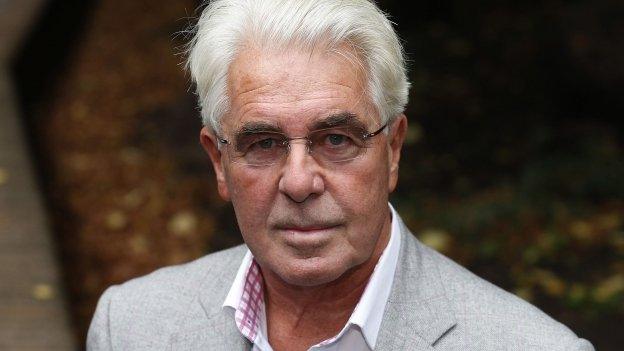

Max Clifford strived to portray an image of a confident, successful businessman

The man who built his career on manipulating the press approached his trial in much the same way, trying to manage coverage of his case.

From the April evening a year ago when Max Clifford appeared in front of the wrought-iron gates of his Surrey mansion to claim that he had "never indecently assaulted anyone", it was clear that he would use all his media experience to project an air of innocence, and maybe influence the stories about him.

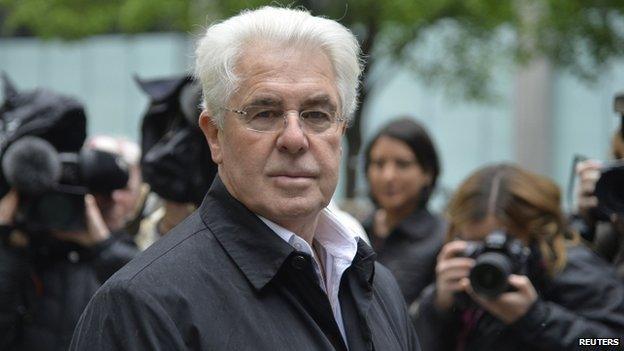

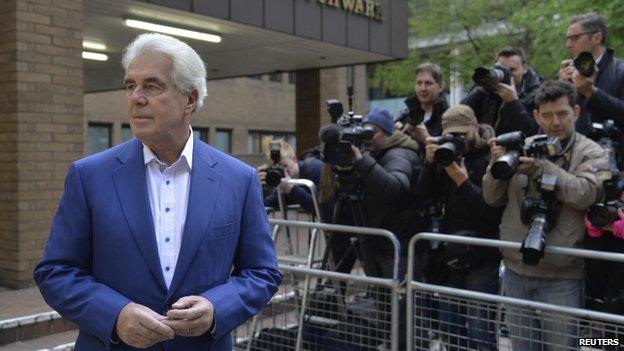

Every single day of the six-week trial he stopped and posed for photographers on the court steps four times: on his way into court, on his way out at lunchtime, on his way back in for the afternoon session and before he left for home.

His sombre expression never changed, his clothes were always immaculate, his back straight. The image was of a poised, successful man, confident he would beat the serious charges against him.

Chatty and avuncular

He always made sure that the assembled photographers and video journalists had all the pictures they needed. This was not someone who was going to let a snatched picture of him rushing off appear in print, leaving readers and viewers (and possibly a jury member) with the impression of a man burdened with guilt.

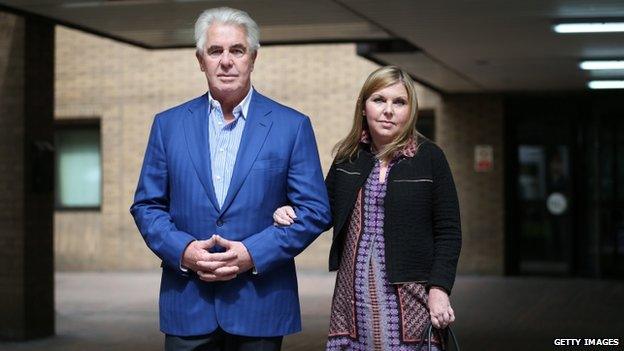

Max Clifford outside Southwark Crown Court with his daughter Louise

On the day his daughter Louise gave evidence he went to extra lengths to ensure he got the coverage he wanted. Louise, who has severe arthritis and clearly finds walking difficult, had already left the court and was waiting for her father in his car. When he arrived on the steps he went to the car, opened the door, helped his daughter out and had her walk back up the court steps to stand next to him, thus limiting any potential media speculation about their relationship.

To the press assembled inside waiting for proceedings to start, he was chatty and avuncular, issuing cheery "good mornings", complaining about particular tweets, and telling us who was lined up to appear on his behalf. "Des O'Connor is definitely on today," he told us more than once. His barrister, Richard Horwell QC, had said he didn't want to turn the proceedings into a "celebrity extravaganza" and he kept that promise.

A bemused-looking Des O'Connor did eventually testify to Clifford's good character for about 10 minutes, as did Birds of a Feather actress Pauline Quirke, but they were the only celebrities and they knew him only after the period in which the assaults took place.

Clifford's trial began on 6 March at Southwark Crown Court

Clifford's face gave little away as he listened to the evidence against him. Wearing headphones connected to an audio loop, he chuckled and shook his head a couple of times while one woman talked of her experience in his office. Occasionally he became more animated, writing notes for his legal team during their cross-examinations.

Only once did he flash real anger; at the elderly father of a 12-year-old girl he was alleged to have abused in Spain in 1983. It was the allegation which he reacted to most strongly - he described it as "disgusting". The man left the dock glaring at Clifford, who stared back with a look of fury, craning his neck to hold the man's gaze as he walked past him and out of the courtroom. Clifford could not be charged with the alleged incident because it happened abroad, and one of the most hotly-contested allegations of the trial remains an open question.

'Silly little girls'

On the stand he was bullish; dismissive and scornful of the prosecution barrister Rosina Cottage QC, whom he belittled frequently. He portrayed himself as an innocent man who had been terribly wronged by the allegations of "fantasists".

Clifford willingly posed for photos on every day of his six-week trial

He denied everything, but his avowed respect for women was undermined by boasts in his biography about getting a random woman off the street to strip for photos in his office for a bet, and calling others with a fake voice to suggest they had sex with his friends.

He insisted he was sexually interested in older women as opposed to "silly little girls", but admitted having long-running affairs with female employees in their late teens when he was at least a decade older than them.

There were two Max Cliffords presented to the jury. The prosecution portrayed him as a manipulative sexual bully who drew in vulnerable young women and girls to abuse. His defence painted a picture of a respectable businessman with an appetite for innocent fun, a deep love for his family and tireless work for charity.

Max Clifford did all he could to reinforce that impression, but in the end the man who built a career as an image-maker could not convince the jury that he had nothing to hide.

- Published28 April 2014

- Published28 April 2014

- Published28 April 2014