The secret world of the UK's immigration removal centres

- Published

Catrin Nye hears from current and former inmates of UK immigration removal centres

Every year, tens of thousands of would-be immigrants to the UK are taken to detention centres while the authorities seek to deport them. What happens to them once they get there and become isolated from the outside world?

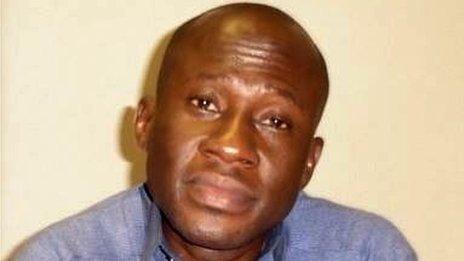

Edwin Sandy is watching a football match between fellow inmates at Dover immigration removal centre in Kent, as he tells the BBC what life in detention is like.

"Who's playing? There's Albanians, Sierra Leone, French, Arab, Moroccan. Very international match," he says.

Dover holds about 300 people, and there is tough competition to be one of the 10 selected each day to play football.

Despite the camaraderie of the game, Sandy feels isolated because so few of the other inmates have English as their mother tongue.

"Every day you meet new people, people coming in and out, and different nationalities. There's a language barrier. It's like a mental asylum, it's very crazy," he says.

The removal centre at Dover houses 300 people

Sandy gives his account of life inside the centre by mobile phone - reporters are not allowed on the premises.

Now 35, he says he came to the UK from Sierra Leone when he was 13, but recently lost his right to remain in this country because of an 18-month stay in jail after being convicted of kidnapping a woman he lived with in 2001 - a conviction he continues to contest.

The authorities in Sierra Leone have denied him the right to live there too, because they say his passport is a fake.

When an attempt was made to deport him, he was sent back to the UK, where he was detained.

There is no time limit restricting how long detainees stay, although the Home Office says most are removed within two months.

Some, like Sandy, stay far longer.

"I've actually been here 10 months now and I'm starting to feel stress now. I don't sleep at nights. I spend a lot of time thinking about what the outcome is going to be like," he says.

Edwin Sandy talks to Catrin Nye

Like most detainees, he has had to share sleeping accommodation for some of that time, and was one of six in the same room at one point.

He now has his own room, but says the conditions in which he is being held add to his anxiety.

He says: "The food in here is rubbish. People spit on the floors, there's people even using showers as toilets. It's very, very shocking."

Sandy is one of a number of detainees around the country whom BBC Asian Network managed to contact.

The often harrowing calls were recorded over a period of three months.

In the recordings, the inmates tell variously of jail-like conditions, of fights breaking out, and say their medical complaints are not taken seriously by staff.

Nozuko is being held at Yarl's Wood immigration removal centre

"The healthcare? You go there, they tell you you are faking it. Any time you go to healthcare, they say you trying to help your case," says a woman who gives her name as Nozuko, and says she is from South Africa.

Four months ago, her working visa expired and she was brought to Yarl's Wood detention centre in Bedfordshire - a facility mostly for female detainees - where she is still waiting for her asylum claim to be heard.

Tiny wage

One of the many complaints she makes about life in Yarl's Wood is the use of detainees as cheap labour.

Although technically unable to work in the UK, special legislation means inmates can be employed within the centres, serving food or cleaning.

The centres are exempt from the minimum wage, and the detainees earn a tiny wage, which they can spend in the centre's shop.

"The women here are not legally allowed to work outside detention. But when they get to Yarl's Wood, they can work, they can do cleaning, they are employed, for £1 an hour," she says.

"What is that? Is that the law?" she asks, indignantly.

A detainee calling herself Nozuko talks to reporter Catrin Nye

Between them, the 13 immigration removal centres in the UK can hold about 3,000 people at any one time.

More than 30,000 people passed through them in 2013 - and Nozuko says the high turnover brings its own problems.

"You get used to this roommate and then they are gone. They are taken back home. Then you get another person, they are crying. You see women as old as your mother," she said

"You are sleeping and men are going to open your door. There is no dignity in this place."

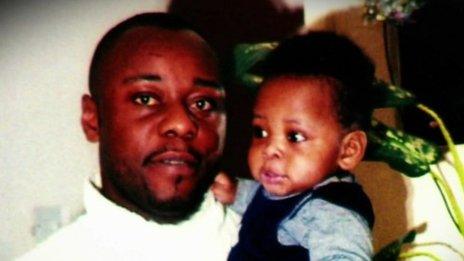

Shinda Bajwa speaks to the BBC from Harmondsworth immigration removal centre in Middlesex, the largest in Europe.

He complained of bullying by staff and having his pictures torn down from the wall of his room.

"It is worse than prison. To be honest to you, I want to even go to prison, prison is better than this," he says.

He is 35 and from India, and was discovered to be in the UK illegally after he was arrested for shoplifting.

The BBC spoke to Shinda Bajwa in Harmondsworth

Bajwa agreed to be deported 11 years ago - but India refuses to allow him to return because he has no passport.

So he is in limbo, and has been in and out of detention ever since.

Some craft activities are laid on for the inmates, they are allowed to watch TV and to study and use the internet.

Bajwa says he is in no mood to use any of the facilities though.

"I really don't know what to do. I'm just stressed out. I can't sleep, because I don't know what will happen. I cry all day, I stay in my room and then I just cry all night. It's not a life."

The Home Office says that detention and removal are essential elements of an effective immigration system and it detains people for as little time as possible.

"Detention is used as a last resort. Detainees' welfare is extremely important and we are committed to treating all those in our care with dignity and respect," a Home Office official says.

Security is tight at Britain's immigration removal centres

Bajwa was released from detention on bail around two months after he first began speaking to the BBC, by a judge who ruled that the Home Office had proved unable to remove him.

He now wears a tag to monitor his movement, which he describes as another form of detention, and he is worried he might be taken back to one of the removal centres that caused him so much distress.

"I am out of detention, yeah, but I'm not free," he says.

"If they want to put me back in detention, keep me, what can I do?" he says.

Additional reporting by Stephanie Harvey and Daniel Gordon.

You can listen to Catrin's full documentary, The Detained, online now.

- Published20 January 2014

- Published20 March 2014

- Published29 November 2013