WW1: The conscientious objectors who refused to fight

- Published

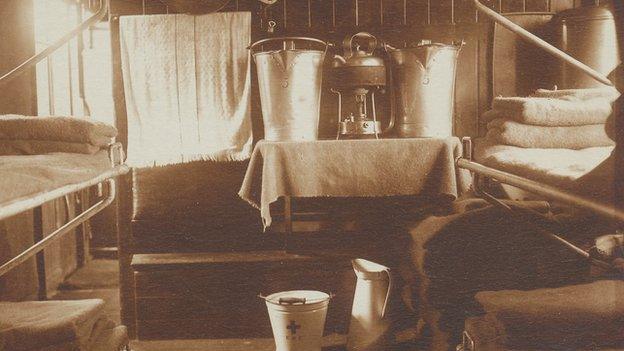

The FAU Ambulance Train worked under the Red Cross to help those injured in the fighting in France

A ceremony is honouring those who refused to fight in World War One. Their relatives look back at their decisions and reflect on the legacy of conscientious objection today.

"He rarely spoke about what happened to him," says Chris Lawson, 76, of his father, Bernard, a Christian objector from north London.

Bernard Lawson was willing to work with the FAU and helping the wounded

"He certainly had a tough time getting through the tribunals. The military were determined to get everyone they could."

Bernard Lawson was one of some 16,000 conscientious objectors who refused to fight as conscription laws enlisted two-and-a-half million extra British troops from 1916 onwards.

'Aggressive' tribunals

Those who objected had to appeal in public, usually on moral or religious grounds. It was not an easy process.

"Most tribunals took a very aggressive view, trying to catch men out and ridiculing them," says author Cyril Pearce, creator of a database of conscientious objectors from the era.

It was only after an appeal tribunal that the military finally accepted Bernard Lawson's Christian convictions and granted him "conditional exemption" - as long as he joined the Friends Ambulance Unit in France instead, evacuating injured soldiers by train.

But those whose arguments were rejected by the tribunals faced a difficult choice: did they answer the call-up or wait to be arrested?

The inside of an ambulance train, used to ferry wounded soldiers away from the front

Once drafted into the Army, men disobeying orders faced a court martial. Anyone who fled the front could be shot.

'Conchies', as they were known, attracted considerable stigma among peers, says WW1 historian Dr Gerry Oram.

"The Army was carrying out massive offensives that went on for months; hundreds of thousands died. Powerful resentment built up towards conscientious objectors, especially where people had lost sons, husbands."

Absolutists and prison

Conscientious objectors were made to take on medical roles and other "work of national importance" on the roads and land.

"But policy towards them grew harsher as the war went on," says Mr Pearce. They could be placed as far as 100 miles from home with a soldier's wage to ensure "equality of sacrifice".

Bernard Lawson was willing to work in France helping the wounded but some conscientious objectors went further, refusing to be involved in any part of the war machine.

A staunch absolutist, Tom Attlee was imprisoned from January 1917 to April 1919.

Tom Attlee moved his family to Cornwall after the war

He had been on holiday with his brother, Clem, when war broke out in 1914.

"They went off in different directions," says Cath Attlee, Tom's granddaughter.

While Clem enlisted - and later went on to lead the Labour party and become prime minister - Tom felt "very strongly" that his Christian principles meant he couldn't do anything to support the fighting.

Little is known of his treatment, says Ms Attlee, but he never returned to his previous work as an architect or his pre-war London lifestyle - instead moving his family away for a very different life in Cornwall.

Ms Attlee is among a number of relatives attending a service in memory of conscientious objectors, organised by international Catholic peace organisation, Pax Christi.

'White feathers'

Cindy Sharkey, 66, is remembering her grandfather, Eleazor Thomas. A socialist member of the Independent Labour Party, Mr Thomas was a conscientious objector railing against what he saw as a capitalist war, waged to preserve the empire.

He was imprisoned at Dartmoor, where he laboured in gas works, Mrs Sharkey, 66 recalls.

"The hardest thing must have been making a choice that meant leaving his wife and children behind with no support as he went to prison," she says.

A family album picture shows Eleazor Thomas in 1938 at the age of 53

But it was possibly worse for his family. "There are stories of white feathers (a symbol of cowardice) and of my grandmother running the gauntlet of abuse down the street to Dartmoor, taking the tiny boys with her to visit him."

Doors were slammed and people hurled insults. The vicar refused to help.

'I'm not fighting'

So what's it like having a CO in the family?

"I have nothing but admiration for the stand my grandfather took," says Ernest Rodker, 77.

"It would have taken some courage to have said, 'Well I'm not fighting for Britain or against the Germans.'"

His grandfather, John Rodker, was a poet-publisher living in the very poor conditions of east London.

"He wasn't political," says Mr Rodker. He was a member of a group of Jewish intellectuals and artists called the Whitechapel Boys and he rejected the war as a battle for influence.

In 1914, aged 20, John Rodker was arrested and imprisoned.

"They laid a path for others who weren't prepared to fight in war," says his grandson.

And he knows personally what this means.

'Very civilized'

Mr Rodker was called up in the last wave of post-WW2 conscription in the late 1950s, but became a conscientious objector over nuclear weapons.

Ernest Rodker, 77, who lives in London, was a conscientious objector in 1958

"By that time being a CO was something you could do. I didn't get abuse and people listened to my arguments at a tribunal, it was very civilized."

Indeed, numbers of conscientious objectors rose from more than 16,000 in WW1 to 60,000 in WW2. During the Vietnam War, hundreds of thousands applied for deferment.

Despite being controversial in WW1, Mr Lawson insists it is "to Britain's credit" that, during a war with a great need for conscripts, conscientious objection was allowed by law.

There are still many countries where this is not possible, he says.

Looking forward to the London service, Ms Attlee is proud to be able to publically honour her grandfather.

"My other grandfather was actually killed in WW1. I always wear a red and a white poppy on Remembrance Sunday."

But without conscription today "it's incredibly hard" to tell how far our attitudes towards conscientious objection have really come, she says.

Mr Lawson reflects: "We're living at a time when we're given a lot of positive imagery about the military - perhaps it's actually getting harder to question it."

Discover how conscientious objectors were treated and more about the war at World War One Centenary and by following @bbcww1, external.