D-Day 70th anniversary: Southsea remembers Normandy voyage

- Published

A band from the Royal Marines School of Music welcomes a team of Royal Marines as they arrive at Southsea

Seventy years ago today thousands of men lined up on makeshift jetties beside South Parade Pier in Southsea to board the landing craft that would take them across to France and D-Day.

For a time, the Allied Supreme Commander himself, General Dwight Eisenhower, watched them embark. "Good old Ike!" they're said to have shouted when they recognised him.

Though Eisenhower's experts had correctly forecast a break in the prevailing bad weather the following morning, D-Day itself, on Monday, 5 June the wind was up and the seas were rough.

Many of those who made the crossing through the night were badly seasick. Some would never return.

Today the weather was very different.

A cold, stiff breeze first thing fell away and the sun shone from a cloudless blue sky as men from all three services - along with contingents from France and Denmark - held a drumhead ceremony in the shadow of the towering Navy war memorial on Southsea Common.

British Marines and their Dutch counterparts held a reconstruction on the beach

Princess Anne was there for a service meant both to commemorate the dead of D-Day and honour the survivors - not just those who fought on the beaches but also the thousands of civilians in cities like Portsmouth whose work was vital to the war effort and who shared in the privations and the dangers, not least from frequent German bombing raids.

Many citizens of modern Portsmouth had come out to watch. They applauded as the contingents of servicemen and women marched off towards Southsea's seafront D-Day Museum at the end of the ceremony.

The men embarking at Southsea on that windy day 70 years ago were part of Assault Force S, the British units destined for the easternmost of the five invasion beaches - codenamed Sword.

Radar station

By the end of the day almost 29,000 troops had been put ashore there, including 176 Free French Commandos given the dangerous honour of being first out of the boats.

The casualties they suffered were much lighter than those inflicted on American troops further west at Omaha and Utah beaches.

Even so, once safely ashore the attack stalled and it wasn't until a fortnight later that the men of Assault Force S finally took the nearby town of Caen, which had been their objective for the first day.

The Princess Royal saluted as veterans marched past during a drumhead service

Among those landing on Sword - although he had embarked at Hastings, not Southsea - was Dugald Buchanan-Morton, a Royal Marine Commando and member of a group tasked with taking a German radar station.

He is now 93 and and has lived on the Isle of Wight since 1970.

Dugald, who retired from his job driving heavy goods vehicles at 81, is a matter-of-fact hero whose own account of D-Day suggests there was nothing much to it.

"We charged up the beach, cut down the wires and everything else to get through the fences and headed up towards the radar station," he said.

"We had a wee scuffle here and a scuffle there and then took over the radar station.

"Anybody that didn't want to come along got shot."

When I suggested he made it sound easy, he answered: "It was".

What was D-Day?

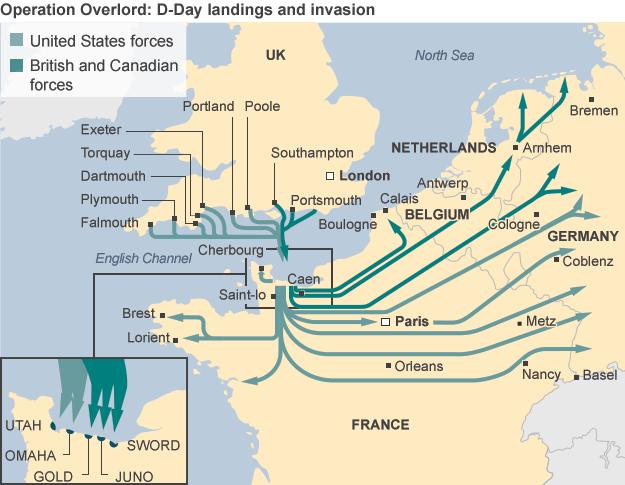

On 6 June 1944, British, US and Canadian forces invaded the coast of northern France in Normandy.

The landings were the first stage of Operation Overlord - the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe - and were intended to end World War Two.

Portsmouth's D-Day Museum says as many as 4,413 Allied troops died, external on the day of the invasion - more than previously thought.

By the end of D-Day, the Allies had established a foothold in France. Within 11 months Nazi Germany was defeated, as Soviet armies swept in from the east and captured Hitler's stronghold in Berlin.

Friendlier welcome

But then the commandos had trained for their role over and over again. No doubt it helped that they had real experience at the sharp end too: Dugald took part in the Allied landings on Sicily and at Salerno in Southern Italy as well as D-Day.

Commandos came ashore in inflatables, speedboats and D-Day-style landing craft

He claims not to have been apprehensive at the time but also admits to occasional nightmarish "flashbacks" even now, 70 years on.

A little later in the morning a Dutch assault ship and its British equivalent, HMS Bulwark, sailed close inshore and through the entrance to Portsmouth Harbour as part of a demonstration of what modern-day amphibious landings look like.

British and Dutch commandos came ashore in inflatables, speedboats and D-Day-style landing craft, both small and large.

A tracked personnel carrier emerged from one craft and powered up the beach, close to where the Portsmouth-Ryde hovercraft makes landfall and on to the road. There was a brief mock battle with unseen assailants and two helicopters brought in reinforcements.

But the bullets were blanks and the whole exercise mercifully just play-acting, unlike the real thing all those years ago.

Later HMS Bulwark will set sail at the head of a small multi-national convoy, carrying a few veterans back to France. Their journey will be quicker and a good deal more comfortable than that other voyage in June 1944.

And this time they can be sure of a much friendlier welcome on the Normandy beaches.

- Published5 June 2014

- Published5 June 2014

- Published5 June 2014