Tracking Scottish referendum opinion on the Glasgow-London train

- Published

The approach to Euston station on the West Coast Main Line

As the West Coast Main Line train contract is extended, the track that can be seen as the backbone of Great Britain is a permanent physical manifestation of the link between Scotland and England. But what do passengers think of the independence referendum?

Get on a train pulling out of Glasgow Central Station on a summer's day. The city that straddles the River Clyde and boasts handsome Victorian architecture and a thriving arts scene soon disappears into the distance.

Coach E on the 16.40 to London Euston is about half full.

It is not immediately clear how many of those aboard will make the 401.25-mile (645.75 km) journey between Glasgow and London.

The West Coast Main Line, with its sister railway track, the 393-mile (632 km) East Coast Main Line that links King's Cross, London, and Edinburgh, are two of the busiest passenger and freight routes in the UK.

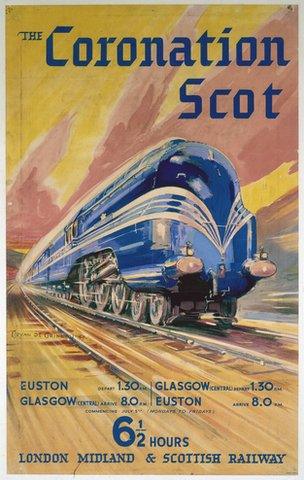

The two tracks have fought a long rivalry to be the fastest north-south and south-north route since the 1890s "race for the north", with various train incarnations coined the Coronation Scot, the Royal Scot and the Flying Scotsman.

The Royal Scot first ran in 1862

A cursory internet search throws up more recent examples of the charge towards speedier connections.

"Glasgow to London by train now 30 minutes faster", the Herald declared, external in 2008. "High-speed rail line could link London to Glasgow in two hours", the Guardian suggested, external in 2009. "Four-hour Edinburgh-London train journeys in 2019", the Scotsman said, external last year.

So how do some passengers feel about the Scottish referendum, which may create more of a distance between the cities?

Two travellers making the entire journey are Charleny Olliffe, 26, and Kirsty Richly, 29. The Scottish women, who both work for the Post Office and are going to London for a training course, both intend to vote "No" in the referendum on 18 September, when voters will be asked the Yes/No question: "Should Scotland be an independent country?"

"I'm from Perth, where a lot of people are going to vote 'Yes'. All my family are 'Yes' people. But I think it's a big thing to say 'Yes' to when I don't think we have all the facts," says Ms Richly.

Ms Olliffe, who is from Glasgow, agrees. "I don't think the 'Yes' campaign handled the currency debate very well and we still don't know what would happen. My brother, who is 17, is definitely going to vote 'Yes' though," she says.

Turnout at the Scottish referendum is expected to be high. Scottish nationalism is more of a mainstream political concern than during the industrial revolution, when the first trunk line - Robert Stephenson's Euston to Birmingham - was created and played a key role in trade and commerce.

"The train line connected the textiles in Manchester, the metal trades in Birmingham, the great imperial port of Liverpool and the centre of shipbuilding and manufacturing in Glasgow," says Russell Hollowood, of the National Railway Museum.

When the train stops at Motherwell in North Lanarkshire, once home to most of Scotland's steel production, another Scot airs his opinion.

Paul McLennan, 48, has lived in London for 28 years so he won't get a vote. But he says all his family will vote 'Yes'. He argues: "London has taken a lot from Scotland. The British government has taken their share of Scottish oil. It's time for them to be a free country."

Fellow passenger David Stroud, 25, has a different reason for supporting the 'Yes' campaign. "I've lived in Glasgow since I was 18 but I'm Welsh. If Wales had the financial resources to go independent then I think it would try to go the same way," he says.

As the train speeds past long stretches of hilly, heathery landscape peppered with sheep and wind farms - Scotland hosts more than half the UK's onshore turbines - towards Carlisle, 10 miles south of the Scottish border, it's easy to see why others have a more romantic vision.

"I'm a Lancashire lad but my late mother grew up in Glasgow. We used to holiday here, so I often come back to visit," says 68-year-old Graham Storey. "I hope they don't go independent - I don't think any countries in the UK are big enough to go it alone, we need each other."

At Carlisle, civil servant and daily commuter to Oxenholme, Jem Bullimore, 50, gets on the train. He doesn't want Scotland to leave either.

"We are one island. UK governance has got too London-centric but I'd like a representative body in the North West or North East," he says.

The Lake District near Keswick

The passing scenery becomes even more picturesque as the train approaches the Lake District, pulling into Penrith and the village station of Oxenholme before it heads on to Lancaster and Preston.

Journalist Matthew Engel, who travelled around Britain by train for his book Eleven Minutes Late, believes it is one of the most stunning train rides in the UK, and even Europe.

"If it was on a tourist branch line rather than a mainline, people would be standing by the window gasping - even the name Penrith has a distinct hint of wildness about it," he says.

The section was also Queen Victoria's favourite stretch of railway line, according to Hollowood.

One of the passengers boarding at Penrith, Richard Nelson, 43, who works for the Outward Bound Trust, does not think independence will make a lot of difference to his life. "It's not something people are really talking about in the Lakes," he says.

However, accounts clerk Dawn Dunnachie, 55, who gets on at Preston, says she doesn't have a choice. "I married a Scot. Much to my husband's disgust, where we live - Tillietudlem, near Lanark - is more of a 'No' area. But he'll be voting 'Yes' and I've been browbeaten by him," she jokes.

The Coronation Scot was inaugurated in 1937 for the Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

As the train whistles on, stopping at Wigan North Western and Warrington Bank Quay, Lancaster University tutor Juliet McDonnell, who has family in Scotland and Scottish friends in England, welcomes the debate.

"It's good to air different views and for the population to decide," she says.

But by the time the train reaches the heart of southern Britain, the physical distance from Scotland is mirrored by the lack of engagement of some passengers. IT support worker Aaron Rattray, 36, who boards the train at Milton Keynes, says: "I'm not into politics so I didn't know it was happening. I don't think it will impact me."

At 21:25 the train pulls into its final station.

The line out of London Euston was the start of the railway age in Britain, according to Engel. Connecting it with Liverpool and Manchester was the "revolution" that tied the country together.

While the same journey can now be made by car or plane, the two static steel threads of London to Glasgow and London to Edinburgh are a permanent fixture in the fabric of the UK.

"Both railways have been incredible unifying forces in making Britain one country - but it may not be enough to hold them together," says Engel.