Helping children cope with a parent in prison

- Published

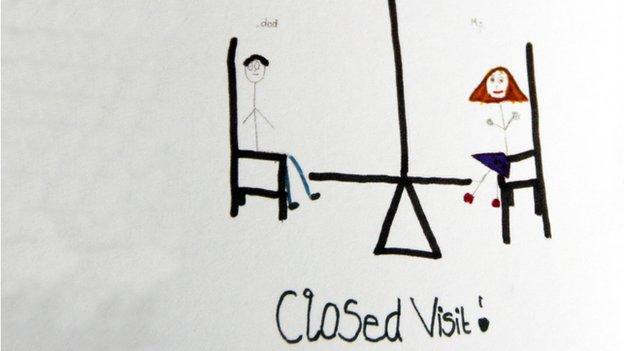

Children at the charity have written a booklet to give to other youngsters who have a parent sent to prison

A charity is calling for more help for children who have a parent in prison, a situation estimated to affect one in every 100 children in the European Union.

Bethany was eight when her mother was sent to prison. Her family did not know how to tell her what was happening - so for six months they simply didn't. She wondered why she had moved to a relative's house and why she only spoke to her mother on the phone. Then her family sat her down and explained what had happened.

"I've got no-one, no mum, my life fell apart," she says. "I got bullied, they'd say stuff like, 'You haven't got a mum and you're going to end up like her.' I'd cry myself to sleep."

Bethany tells BBC 5 live: "You go through it with them"

Hers is one of the families being assisted by the Person Shaped Support (PSS) charity in Liverpool, which provides advice for parents on how to talk about imprisonment, and provides children with one-on-one and peer group support.

"They take us for days out," says Bethany. "Sometimes we talk about what's happened to our families but a lot of the time they don't.

"We talk about how it's OK to feel angry about what's happened and what to do if we feel guilty. We have a lot of one-to-one sessions but we also go out in a group - and we learn from each other. I've learnt that you never give up on the people you love."

Bethany's mother has now been released and they are rebuilding a relationship, but it is difficult - Bethany has been on her own for a large part of her childhood.

The children draw pictures to try to express their feelings - Bethany's shows the alienation she felt at school

"My mum's been out for a while now and it's hard to speak to her because I don't want to upset her. She's getting back to where she wants to be. Sometimes I think I can handle it but I can't, I need people to talk to.

"I've learnt to take care of myself, be responsible, be mature but I still need people to talk to. It's not that I'm scared, but I'm still only 13."

'A shock'

Barnado's estimates that there are 200,000 children in England and Wales affected in this way, 30,000 in Scotland and 1,500 in Northern Ireland - though no official figures are recorded.

Arrest and imprisonment can have dramatic consequences for families. Grandparents can find themselves suddenly having not only to remember how to parent, but deal with a whole set of issues they never knew about beforehand.

When Doreen's son Craig was sent to prison - we were not told what for - she was asked to look after his three sons because his wife was also in jail.

"It was a shock," she said. "The first thing that happened was the children were brought to me. Then you get social services on your doorstep." The memory brings tears to her eyes - the bitterness at being "checked up on" barely hidden.

"They dig into your background - I just didn't expect to be treated the way I was."

Craig is now out on parole, but the children still live with their grandmother, and their visits with Craig are supervised.

Jack, 15, explained how he reacted when his dad was sent to prison.

"I sat around for about a week and then thought, 'I've got to get my head down and work. I've got to think about myself.'"

He says he did not see his father for up to four months because he was only allowed closed visits, in which the prisoner and the visitor are divided by a screen.

"It's not nice to see anyone behind glass but he's my dad, he's always been my dad," he says, looking up at his father. "It's still hard, my mum's still in prison, but at least I've got my dad out and he can help me, and I speak to her as often as I can."

All the young people at the charity seemed mature beyond their years - Jack was able to talk eloquently about how speaking to his dad on the phone while he was in prison helped his father more than himself.

Breaking stereotypes

But Craig struggles to put his feelings into words, perhaps because it is so hard confronting how he feels.

"They've all grown up a lot quicker than I expected because they've had to deal with all sorts of things themselves. I feel a lot of guilt. All I want to do is get the family back together, pick up the pieces and rebuild the jigsaw," he said.

This is not an area that attracts money easily, and there is no central support for PSS's work. In the past, Barnardo's has appealed for the government to assign a minister to cover prisoners' children.

But PSS says its work can dramatically change the children's futures.

"With support, the children can break every stereotype in the book, they just need some help to get through it all," says Lorna Brookes, who works for PSS with offenders' families.

The risks they face involve an increased likelihood of mental health problems, living in poverty and poor housing. Some studies suggest that separation by imprisonment can lead to criminality "running in the family".

The charity tackles these risks by involving the whole family, in order to help children come to terms with the separation and to talk about their fears. It has also produced a booklet written by children to help others who have parents sent to prison.

As Bethany says: "I still remember what it felt like when she went away. But you do have a mum and dad - it's just that they're not in that particular place with you.

"I do have a mum. She's done a mistake and she can be someone different. You do not give up. The people in prison - you do the journey with them, you help them. I see happiness in my future, I see family. I can't wait to have the journey towards that."

The names of the children and adults helped by PSS have been changed.

Listen to a podcast of Prisoners' Children on Radio 5 live

- Published10 June 2014

- Published25 October 2013