Scottish independence: How would 'Yes' vote affect Northern Ireland?

- Published

Scotland can be seen from Northern Ireland on a clear day - but not when clouds appear

Scotland and Northern Ireland have a long history of cultural ties and economic links. But if Scotland votes "Yes" to independence in September, how would people in Northern Ireland feel and how might it affect politics?

On a sunny day in the small coastal town of Donaghadee in County Down, south-west Scotland shimmers on the horizon.

There's barely 20 miles (30km) of narrow sea between the Celtic coasts.

But it's not just geographical proximity that connects Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Millennia of migration - most famously in the 17th Century, when the plantation of Ulster saw English and Scottish Protestants move over in droves to what is now Northern Ireland - has intertwined their history, culture and language.

There has also been plenty of migration the other way, most notably in the 19th Century around the time of the Irish famine, but also for employment, first in agriculture and then in heavy industry.

Plenty of family ties and friendships still stretch across the water.

There are also strong sports links. Glasgow football club Celtic was formed by Irish Catholics who began emigrating to the west of Scotland in the 1840s, while Rangers, which was set up at a similar time, has always been perceived as the Protestant club. Both have a huge fanbase in Northern Ireland and supporters regularly make trips to Scotland.

And there's a long history of students in Northern Ireland heading to Scottish universities to pursue their studies.

So how do residents of Northern Ireland, some of whom may have stronger connections with Scotland rather than England or Wales, feel about the Scottish referendum?

In a place where politics is dominated by beliefs in unionism and nationalism, and those beliefs are broadly subscribed to along Protestant and Catholic lines respectively, it would be easy to think that Catholics would support a "Yes" vote and Protestants would push for a "No".

But there are strong links with Scotland in both Protestant and Catholic communities.

Unionists could, however, go through a whole process of self-examination - an identity crisis even - if Scotland votes for independence, because the nation is such an important part of the union to which they belong, according to Graham Walker, professor of political history at Belfast's Queen's University.

Sentiments run high at Belfast's Sandy Row Rangers Supporters Club

Rangers supporter Jim Wilson says a Scottish "Yes" vote would be a massive shock

"If Scotland goes there will be at least a period where unionists will be in some kind of disarray - defensively circling the wagons - wondering how to adapt or see if they can find a way forward politically that maintains their own identity but also their relationship with Scotland," he says.

Sentiment is certainly strong at Belfast's Sandy Row Rangers Supporters Club, where Saltire and Ulster flags and Glasgow Rangers shirts adorn every wall and the kerbstones outside are painted red, white and blue.

East Belfast community worker Gary Lenaghan, 51, says Northern Ireland's Scottish links are "unbreakable" and he would be "gobsmacked" if Scotland voted for independence.

"If that happened I think an influx of people might move from Scotland to the remaining part of the UK to stay in the union, and their first choice of residence would probably be Northern Ireland," he says.

Dr David Hume is attending a pro-union Scottish Orange Order march in Edinburgh

Fellow Rangers supporter Jim Wilson, 62, agrees it would be a "massive shock" if Scotland voted for independence. If it does, he believes the fall-out might move Scottish politics closer to Northern Ireland's.

"Not in a physical violence way, but I can see it turning into saxonised politics - voting for pro-union candidates in the future," he says.

Other unionists are taking steps to try to ensure a "Yes" vote doesn't happen.

Dr David Hume, director of services at Grand Orange Lodge in Northern Ireland, says he and thousands of the organisation's members will participate in a Scottish Orange Order march in Edinburgh five days before the Scottish independence referendum.

"One hundred years ago the Grand Lodge of Scotland showed very strong support for unionists here when they were opposing home rule, so 100 years on we feel it's most appropriate we show our support.

"We see ourselves as Ulster Scots and feel very strongly attached to our friends and relatives in Scotland. It would create a whole range of complexities if Scotland left the union," he says.

Hume has previously called for people in Northern Ireland with Ulster Scots backgrounds to be given a vote in the referendum but it didn't come to anything.

But while unionists might face a period of mourning if Scotland goes independent, a "Yes" vote could be an enormous boost for nationalism.

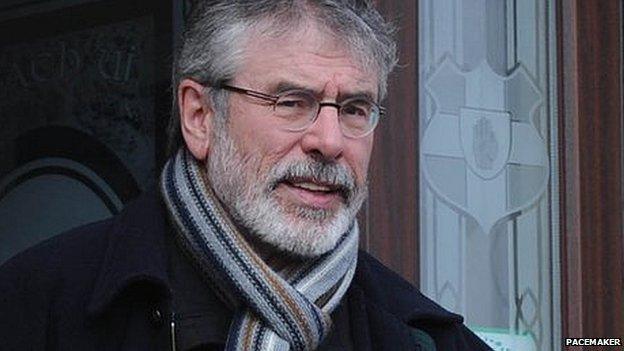

Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams has largely stayed out of the debate on Scottish independence

Earlier this year Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams said the "so-called United Kingdom" was held together by a thread that could be unravelled by the referendum in Scotland.

The party, which campaigns for Irish unity, has so far stayed out of the debate, saying it's a matter for the people of Scotland.

Currently support for a united Ireland in Northern Ireland remains relatively low. Last year a BBC Spotlight poll suggested there was a 65% to 17% majority for Northern Ireland remaining in the UK.

However, Scottish independence would reinforce nationalist demands for a referendum on a united Ireland - a move that is allowed no more than once every seven years under the 1998 Good Friday peace deal.

The Orange Order is holding a pro-Union rally in Edinburgh five days before the Scottish referendum

Nationalist marches are much fewer in number in Northern Ireland

Walker believes there is a divided opinion among nationalists. "There is certainly a body that thinks the more the UK breaks up the better - that it might increase the chances of a referendum on Irish unity," he said.

"But another body of opinion in the Catholic community would be cannier - they'd see the bigger picture, particularly in terms of looking down south and thinking the Dublin government has no wish to see Scotland leave the UK - and it wouldn't really help them in terms of their long-term aspirations in both parts of Ireland."

Northern Irish nationalists are also "quite hesitant" to get involved in the Scottish referendum debate because the Catholic community in Scotland of Irish descent is "a bit split on the issue," he says.

"There would be many in the Catholic community in Scotland who have a strong tribal loyalty to Labour, which I think in most cases translates to a 'No' vote, but there is evidence quite a sizeable number of Labour voters in that community are moving towards independence and the SNP, so it might be they feel they can't actually say you should go for it."

While the knock-on effects of a Scottish "Yes" vote on the politics of Northern Ireland can only be speculated about, there is certainly a sense it could rock the relatively recent stability of Northern Ireland's power-sharing government.

There is also some concern the Barnett formula - the method for working out how much money is given for public spending in each of the UK's nations, which currently sees Northern Ireland get more cash per head than Scotland, Wales or England - might be reconfigured.

However for Walker the biggest concern is how unionists might react.

"It could stoke loyalism and send it into a tailspin - perhaps around issues like parading and flags, which are so problematic. Some people would fear for the peace process, at least in the short-term," he says.

A referendum on whether Scotland should become independent is to take place

People resident in Scotland will be able to take part in the vote, answering the "Yes/No" question: "Should Scotland be an independent country?"

The referendum will take place on Thursday, 18 September, 2014

Go to the BBC's Scotland Decides page for analysis, background and explainers on the independence debate