Analysis: The Prevent strategy and its problems

- Published

- comments

Young Britons have appeared with other extremists in a recruitment video for jihadists in Iraq and Syria

Preventing Violent Extremism - also known as Prevent - has been a government priority for a decade.

But despite millions of pounds, initiative after initiative, the strategy remains deeply controversial, virtually impossible to fully assess and, if its critics are right, fatally compromised and incapable of achieving its goals.

Prevent is one of the four Ps that make up the government's post 9/11 counter-terrorism strategy, known as Contest: Prepare for attacks, Protect the public, Pursue the attackers and Prevent their radicalisation in the first place.

In the early days of Prevent, Whitehall was divided over what Prevent meant: was it purely about al-Qaeda-inspired extremism or was it about other groups as well?

Was it about tackling violence or the underlying ideology?

How could officials work out who they needed to target to get results?

Impossible to assess

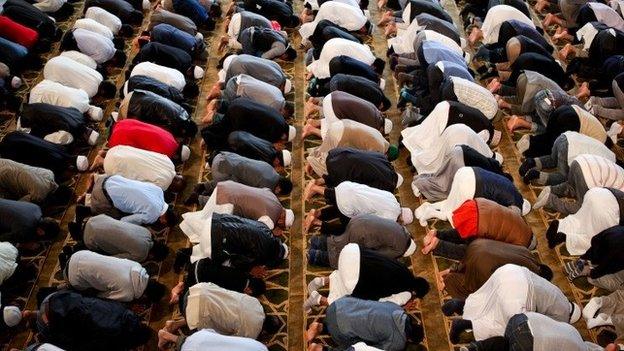

Some British Muslims have complained of feeling targeted by the Prevent strategy

Ministers threw cash at Prevent - particularly in the wake of the 2005 London suicide bombings.

In the six years after those attacks, almost £80m was spent on 1,000 schemes across 94 local authorities.

Security officials wanted schemes to prevent young people from following al-Qaeda's world view.

But other officials saw it as a means of funding pet projects on community cohesion.

Many groups that received funding knew what they were doing - focusing on theology and countering the politics of extremism.

But others had no idea about radicalisation at all - and some believed it was a myth because they had no expert experience and were suspicious of the message.

Very few of the schemes could be assessed to show one way or another whether they worked - officials were often taking the word of the people they were funding.

'Stigmatising Muslims'

There were a few total policy disasters along the way.

I remember one really angry imam from the north sending me some materials that officials had presented to him as a proposal for citizenship classes for teenagers.

Local people interpreted the materials as implying that al-Qaeda was behind every street corner, working in every mosque.

You can imagine the fury as government was accused of turning every young Muslim into a suspect.

In turn, some local councils resisted a government attempt to impose a target upon them which would order them to do more to combat extremism.

The councils did not oppose the target because they disagreed with the aim - but they were telling Whitehall that the tactics were stigmatising Muslims.

Some of the groups with the most insight into al-Qaeda complained they couldn't get around the table because they publicly attacked foreign policy.

Prevent was criticised after funds were used to help pay for CCTV cameras in Muslim areas of Birmingham

When the coalition came to power, it promised a clean break.

And one of Prime Minister David Cameron's most important early speeches was a promise to be tough not just on violent extremism - but on the radical "us and them" ideas that underpin it.

Religiously conservative groups that had been funded in Labour's days were cut off.

They were seen as part of the same ideological family tree as al-Qaeda - even if they themselves argued that bin Laden was the black sheep of the family.

But one of the biggest knocks to Prevent came when it emerged four years ago that CCTV cameras in Muslim areas of Birmingham - 72 of them hidden - were partly funded by Home Office counter-terrorism cash.

The loss of confidence and trust in police was enormous.

There have been, however, some successes.

The most discrete part of the broad Prevent agenda is called Channel.

It is an intensive one-to-one mentoring programme to challenge violent views through deprogramming and rewiring an individual.

Channel has turned around some lives - but there will always be some who it cannot help, not least because its resources are limited.

'Suspect community'

Police forces have a specialist network of Prevent officers - and many of them are trying to work out how to combat the pull of Syria.

The latest scheme is a big push to enlist women to help.

Over the weekend Home Secretary Theresa May also proposed changes to the law to tackle extremism and radicalisation in the UK.

She said she was "looking again" at banning "extremist groups" - something first mooted by Tony Blair in the wake of 7/7.

Mrs May has also proposed creating a new power similar to anti-social behaviour orders which would restrict the behaviour of extremists who have a role in radicalisation.

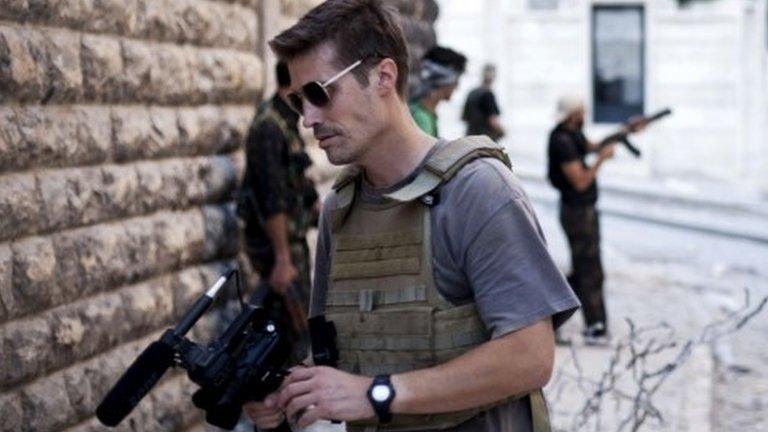

UK authorities are trying to stop Britons going to fight in Syria

But the deputy head of the Muslim Council of Britain, Harun Khan, has told the BBC that Prevent is still alienating the very people government is trying to reach.

Mr Khan said: "Most young people are seeing [Prevent] as a target on them and the institutions they associate with."

So the real problem with Prevent is this: every time officials try to win trust, they are met with the accusation that they are treating Muslims as a "suspect community".

However, police chiefs say such accusations are not supported when you look at the successes they have recently had.

There has been a five-fold increase in counter-terror-related arrests in the past six months - the majority of these related to events in Syria.

Some of these arrests have come as a result of information provided by the community.

Assistant Commissioner Mark Rowley, Britain's most senior counter-terrorism officer, says communities are co-operating with the police - but they need more help.

Nearly half of all the people who have travelled to Syria for a jihadist cause were previously unknown to the security services.

That means extremists who are attempting to radicalise young men and women have been succeeding - and that's why the government's Prevent strategy remains such an important part of the story.

- Published24 August 2014

- Published23 August 2014

- Published25 August 2014

- Published26 August 2014