Why new anti-terror powers aim to disrupt not prosecute

- Published

- comments

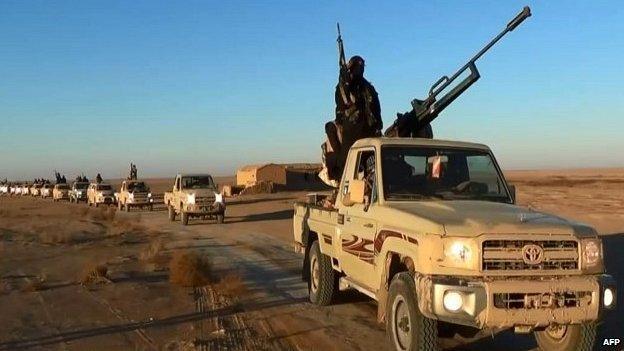

Hundreds of British nationals are thought to have travelled to Syria and Iraq to fight with militant groups

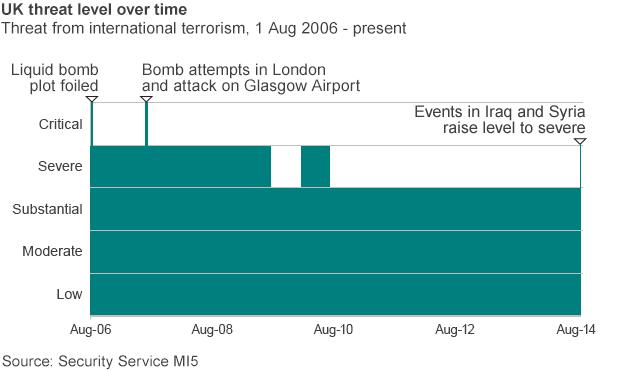

The government has announced a raft of new counter-terrorism powers to combat what security officials regard as a severe threat from so-called Islamic State fighters returning from Syria and Iraq.

These powers are not necessarily aimed at prosecuting more people - they are aimed squarely at disrupting them.

Over the decade or so since 9/11 the UK's counter-terror legislation has been developed to achieve both of these aims. Parliament has created a long list of terrorism-related crimes to make it easier for the police to charge suspects.

During Northern Ireland's troubles, police could use all the obvious laws relating to murder or conspiracy to commit acts of violence.

Today's permanently-enacted counter-terrorism powers are drawn more widely and cover specifics such as training for terrorism - or possession of information of use to terrorists - or glorification of terrorist acts. Arguably the most useful crime is preparing for acts of terrorism because it allows someone to be charged long before they have started acting on plans for violence - one man was jailed for life last year for preparing for attacks.

But politicians also wanted more powers to deter, deflect and disrupt people - the point being that if you disrupt someone long enough they might just stop what they are doing.

So ministers began seeking and using a range of powers with disruption in mind.

The prime minister is expected to consider strengthening terrorism prevention and investigation measures

They included house-arrests powers known as control orders, which were later replaced by a less onerous system, TPims.

Police have a power under the Terrorism Act 2000, known as Schedule 7, which allows them to stop and question people at a port, external. They can also seize cash and other items.

While some people who are subject to these stops may be charged with a crime - many will not. The real effect of the power is disruption.

If MI5 knows of a would-be fighter trying to leave the UK for Syria, their primary goal might be to stop him going.

If he is stopped at the port - and police confiscate a huge bundle of banknotes pending further investigation - he will miss his flight or connections. He will, in all possibility, go home and give up. In security terms, that is mission completed.

The home secretary's use of the Royal Prerogative to seize passports has the same aim, as do Treasury asset-freezing orders.

Enormous U-turn?

The most controversial but least reported of these powers is nationality stripping - the home secretary has used this power increasingly frequently in recent years against suspected jihadists travelling abroad, although it can only be used against someone with another nationality to turn to.

These kinds of powers are repeatedly challenged before the country's top judges - but by the time cases come to court the practical job has been done.

Turning to the new proposals, we don't yet know if the coalition partners can agree on an enormous U-turn over TPims and house arrest powers.

The prime minister's announcement that there will be new laws to make it easier to seize passports is more technical.

They are almost certainly designed to give the government some legal cover because officials have been preparing for a strong legal challenge to the home secretary's use of the Royal Prerogative to withdraw passports.

If she were to lose that challenge, she would have to hand back all the other passports tucked away at the back of her filing cabinet - 23 at the last count.

Nightmare scenario

The most controversial element of the package is the suggestion that the UK may be able to ban temporarily its own citizens from coming home.

This is different to nationality stripping - which allows the home secretary to completely bar someone from returning here - assuming they have another nationality to turn to. But it is currently very hard to see how a temporary ban on returning to one's home country could work because international law is quite clear that governments cannot render someone stateless.

IS extremists have seized large areas of territory across northern Syria and Iraq

If the government could get such a power through Parliament, it could achieve the security services' aim in the short-term of minimising threats - even if over the long-term the law faced repeated challenges. But it's by no means clear whether the proposal is workable. Dominic Grieve QC MP, the former attorney general, was among the first to tell the Prime Minister in the House that he thought it would breach common law - the bedrock of our system - as well as international law.

One way or another, the counter-terrorism toolkit is likely to be expanded - but critics say it won't deal with another problem.

There are many Brits who went to fight in Syria with no intention of joining violent extremists like ISIS. They say they picked up arms to defend civilians from President Assad's regime.

The nightmare scenario for the government is that these people, many of whom have naively walked into a situation they hadn't expected, are scared of returning home and facing arrest. Their families back home fear they could be further radicalised.

And that's why there are voices inside both security circles and Muslim communities who say that the exit plan for returning fighters must amount to more than just prosecutions and jail sentences.

- Published1 September 2014

- Published31 August 2014

- Published30 August 2014