London's GCSE lessons for rest of England

- Published

The government is to start shipping head teachers to Grimsby.

That's the result of an announcement that the Department for Education is to try to get good heads to go to areas that lack good schools.

This is an unglamorous idea, but might mark the first serious attempt to overcome one of the biggest questions in English education - why there is such little progress in school improvement outside London?

Some years ago, when I worked at the Financial Times, I started to publish what one civil servant dubbed the "graph of doom".

It's a simple graph. There's a video explaining all of the decisions behind it here, external.

On the horizontal axis, I plotted the poverty of the children's neighbourhoods.

The left are the children in the poorest areas, the right are the richest.

On the vertical axis, I plotted what was called the "FT score", which describes how children do in a simple basket of subjects.

I awarded pupils eight points for every A* they got at GCSE, down to one point for a G.

I added up their scores in maths, English and their three best other subjects. So five A*s get 40 points. Five Cs get 25.

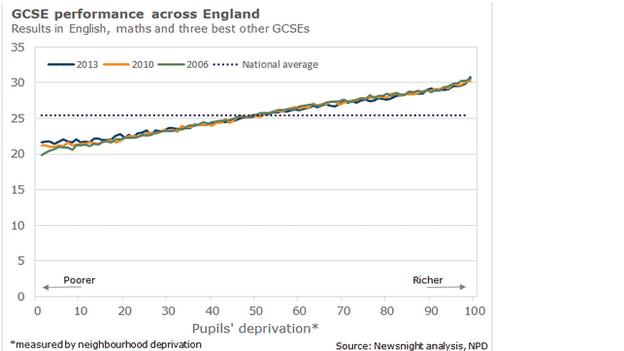

And, by popular demand (honestly!), here are those graphs again, updated to 2013.

I've overlaid the graph with the results from 2006 and 2010, which I've also standardised to account for grade inflation - the tendency to award higher grades for work that might have received lower grades in the past.

As you can see, poorer children do systematically worse than richer ones. The right is higher than the left.

But keep your eyes on the far left-hand side - our poorest pupils. There's been a slight improvement for those pupils from 2006 to 2010, and (slightly slower) from 2010 to 2013.

That's good news. But there's an unsettling feature to it.

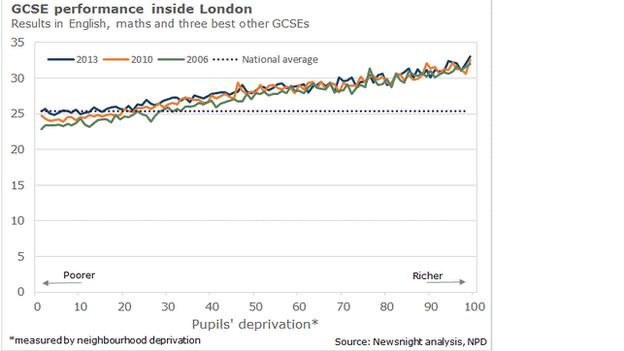

Here is the graph for London. Look at how the poorest children in our capital now beat the national average.

The secondaries are still improving. Slower than before, but they are still going, and London's primaries give them a head start too.

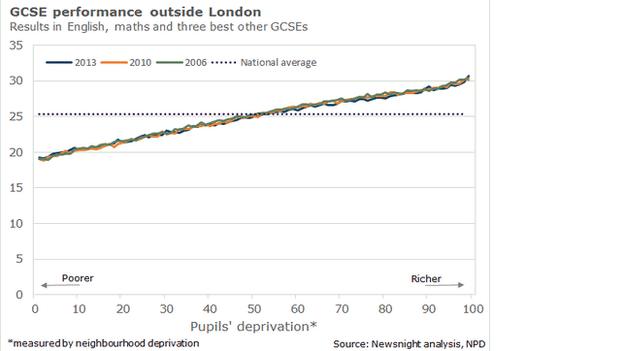

But here is the graph for the rest of the country.

The two things to take from these graphs are first that, for all the change since 2010, the old patterns are persisting.

For all the rhetoric, there's no sign of revolution yet. I'll return to what we can say about what effect all the reform has had so far.

Second, the great successes of education policy in London are still not extending beyond the M25.

We've settled in a world where if you took two otherwise identical 11-year-olds with identical test scores, and put one into a Hackney school in London and one into a Grimsby school, the former would beat the latter by a grade in almost every subject on this measure.

That's why, while this plan to ship teachers north might be blunt and small, at least it is answering one of the right questions - how to close the gap between poor children and the rest outside London.

That is not always the case. Both Labour and the Conservatives have put a lot of faith in academy chains - private organisations - to help deliver progress.

Grammar schools

There is very strong evidence that the early ones worked. But they were mostly in London.

There are, however, still few good chains outside the capital.

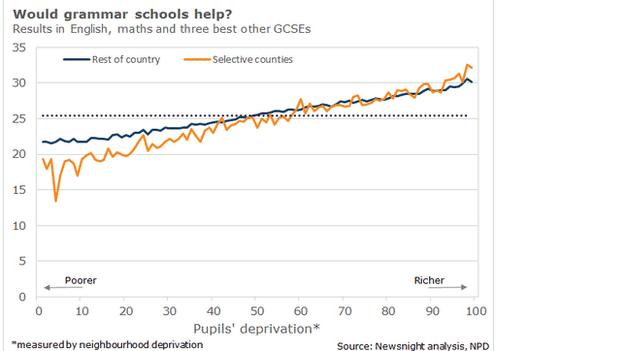

UKIP usually takes a different tack. It backs more grammar schools. But here's another graph on that theme.

It compares results for the big boroughs that operate a selective system (Kent, Medway, Lincolnshire and Buckinghamshire) and the rest of England.

While they may whisk a few children from poverty to greatness, they do not close the attainment gap, and this choice of measure is flattering to the selective areas, since it gives higher weight than most to academic attainment.

You can see that poorer children (the left-hand side) do worse than the rest of the country.

There are a few (well-off) beneficiaries.

Recruitment in the north

This may read like a counsel of despair. It ought not to. The lesson of London is that schools can change.

And this plan to despatch teachers, however meagre, shows that Whitehall is now thinking spatially.

It's giving consideration to the simple difficulty of getting good teachers to work in some of our cities and towns where there are shortages.

That is a big change.

As recently as 2012, the Department for Education put forward proposals that would mean cutting teachers' pay in northern cities (where recruitment is tough) and raising it in London (where it is not).

So keep an eye out for this in election season.

The parties should give more thought to what they can do to improve schools in cities where they are struggling.

- Published10 September 2014

- Published27 June 2014

- Published20 June 2013