RAF veterans remember the Warsaw Uprising 70 years ago

- Published

Seventy years ago these men tried to keep the Warsaw Uprising going

Seventy years ago - on 2 October 1944 - the Warsaw Uprising was finally crushed by the German army, after 63 days. Stalin's failure to help is well known, but few know of the RAF veterans who risked their lives trying to help the Polish resistance.

Flying secret missions on RAF special duties did not involve asking questions.

But when rear gunner Jim Mckenzie-Leith received instructions 70 years ago to fly to Warsaw, he remembers his reaction: "The previous couple of days the squadron had lost four aircraft…it went through my mind…Bloody hell, have we got to go there as well?"

On 14 August 1944 Mckenzie-Leith and his RAF 148 Squadron crew flew supplies to support the Warsaw Uprising.

The Polish Home Army, one of the largest underground armies of World War II, had come out of the shadows to fight against five years of German occupation.

In July 1944 a Soviet offensive on the east broke the German front. As the Wehrmacht began to retreat west through Warsaw, and the Red Army advanced from the east, the Poles decided now was the time.

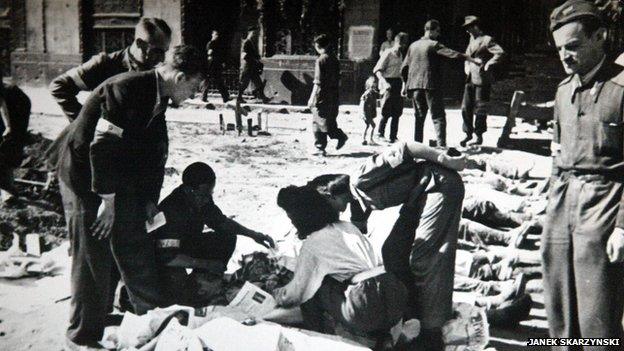

Around 180,000 people died during the Warsaw Uprising

The plan was to reclaim Warsaw from the Germans and greet arriving Soviet forces as equals in an already independent city.

The Polish government-in-exile, headquartered in London, informed the Allies of the plans and were promised support.

On 1 August at 5pm the Uprising began. Three days later Allied airdrops began, flown by British, Polish and South African pilots.

David Lambert and Jim Mckenzie-Leith were two members of a seven-man crew headed by Pilot Lawrence Toft.

Mr Lambert recalls their Warsaw flight, two weeks into the battle: "It was rather terrifying to think of the length of time we were going to be flying, which was longer than any flight we had ever done before."

Stalin had been requested to allow Allied planes to land and refuel in the Soviet Union, but refused to support what he called the "adventure" in Warsaw.

Mr Toft's crew had experience of special duties, dropping supplies and agents to the French resistance in the mountains.

But Warsaw was the first city they'd been sent to. One thing would stay the same, Mr Toft recalls.

The allied airmen who died during the Warsaw Uprising were honoured at a ceremony recently at the Polish War Memorial in London

"In our normal supplying of partisans, somebody on the ground would mark the spot by holding up a torch in the four corners….We were told that this square where we had to drop in the city would be marked by the same torch lights… and they would be held up by girls astride the roofs of the buildings," he said.

This memory is particularly painful.

"The Germans were firing rifles at these girls and shooting them off the roof and another girl would have to take their place. That was sufficient impetus I think for me to go," he recalls.

On the night of 14 August 1944 the crew took off from Brindisi, Italy, with no escort. They flew for more than ten hours, largely over enemy territory.

Warsaw was visible long before they got there.

"It was just before one o'clock in the morning when we could see flames on the horizon," Mr Toft remembers.

"I descended to the Vistula river down to about 300 feet, we were flying along it and the anti-aircraft guns on the west side opened up onto us.

"We were hit but not to stop us continue flying. Immediately the aircraft filled with smoke and the smell of burning."

Mr Mckenzie-Leith also has vivid memories of that night.

Veterans who fought in the Warsaw Uprising and their relatives at a ceremony in the Polish capital in August

"There were flames everywhere. Guns seemed to be firing everywhere. Whether they were firing at one another or firing at us, you couldn't tell. All it was, was flashes".

Their target was Napoleon Square, today known as Uprising Square (Plac Powstancow Warszawy).

Mr Lambert, the dispatcher, was in the centre of the plane and could see nothing of the battle going on outside.

"I had a panel beside the hole in the floor that gave me a green light when to drop the packages. I was just desperate to get rid of my packages," he remembers.

The crew was successful and dropped supplies near Warsaw's Old Town.

"To be so accurate was marvellous," says Mr Mckenzie-Leith.

As they turned to make the five-hour return journey, Mr Toft could not determine whether the plane was damaged, but ensured his men were not.

"I said to the crew, would you all check and see if you have been hit…and then one by one the answer came back, 'I'm OK skipper'," he adds.

Many crews were not so lucky and losses were horrendous - 360 Allied airmen were lost during the Warsaw airdrops.

The Warsaw Uprising lasted 63 days and ended in defeat.

Lawrence Toft, back in the pilot's seat at the Yorkshire Air Museum

On 2 October the Polish Home Army surrendered.

Eleven days later the Polish prime minister-in-exile, Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, met Stalin to discuss future borders.

He was shocked to learn that the eastern territories of Poland had been promised to the Soviet Union in a secret meeting between Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill.

The Tehran Conference had taken place a year before the Uprising began.

Almost 180,000 people died during the Warsaw Uprising, including 20,000 Home Army soldiers.

For months after the city fell, the Germans continued pounding at its ruins, reducing Warsaw to rubble.

The Uprising is honoured to this day. Seven decades after their memorable flight, the crew of RAF 148 Squadron returned to Warsaw for commemorations, along with veterans from around the world.

On meeting Mr Toft, a Polish Home Army veteran was moved to speak. He had been in the square the night the crew flew overhead.

"Thank you Lawrence," he said.

Seventy years after supplies were dropped, confirmation came: the mission had been accomplished.

Warsaw 44: The Uprising, will be shown on BBC World in North America on Saturday 11 October at 09:10 GMT and 21:10GMT and on Sunday 12 October at 02:10GMT and 15:10GMT.

You can follow Lila Allen on Twitter - @LilaWanda, external

- Published21 August 2013