Should all English cities be more like Manchester?

- Published

George Osborne has announced moves to make Greater Manchester a "northern powerhouse". How have efforts to empower the region worked so far, what new powers will it get, and should other cities follow suit?

The chancellor said Greater Manchester will have the first metro-wide elected mayor outside London to oversee policies such as transport, social care and housing as well as police budgets.

He said the move had been agreed with leaders of the region's 10 councils and he will talk to other cities "keen to follow Manchester's lead".

The city of Manchester had a population of 514,000 in 2013, but the broader area is home to 2.7 million people, according to Nomis, external.

It already has more powers than many other English cities. In 2011, Manchester City Council teamed up with nine neighbouring councils to form the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA).

The GMCA was the country's first statutory "super-council" with power to co-ordinate the region's regeneration, economy and transport priorities.

The chancellor's announcement follows several reports that have called for more responsibilities to be handed to Greater Manchester.

Manchester City Council teamed up with nine neighbouring councils in 2011

Right-leaning think tank ResPublica recently recommended, external Manchester should "lead the way" on devolution for cities, with an elected assembly, a mayor, income-tax raising powers and complete control of spending within five years.

The RSA City Growth Commission published a report, external in October that recommended allowing UK cities to make their own decisions on tax and spending as a way of reducing the Treasury's deficit, of which it estimates £4-5bn relates to spending in Greater Manchester alone.

Greater Manchester

Metropolitan area formed in 1974

Made up of 10 councils: Manchester, Salford, Bolton, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, Stockport, Tameside, Trafford, Wigan

Population is about 2.7 million

Covers an area of about 500 sq miles (1,300 sq km)

Has an economy bigger than Wales or Northern Ireland

Designated a City Region in 2011, when the Greater Manchester Combined Authority was established

Before the chancellor's announcement was made, the prevailing attitude to devolution on the streets of Manchester on a weekday in October seemed to be: "Why not?"

Sitting by the war memorial near the Central Library, Abi Mather, 21, says: "People from Manchester love being from Manchester, we take it very seriously. We always know best - why shouldn't that also apply to what money goes where?"

The money generated by Manchester is not insignificant. The ONS reports, external that Greater Manchester added nearly £51bn gross value (GVA) to the economy in 2012.

By comparison, the West Midlands urban area produced £49bn and Merseyside generated £25bn in the same year.

Elaine Smith, 51, agrees that the city can stand on its own feet. "Manchester is on the up - when you look at what's on offer in terms of shopping, transport to get around, the football," she says.

"Maybe southerners think we come second behind London - but people here don't feel that way, so it'd be better if we had as many powers as London."

At the same time, there are those who give the whole idea short shrift.

Tony Richards, 43, a photographer at Manchester Central Library, says: "It all sounds good, but when it comes down to it they always waste money left right and centre on crazy initiatives - it doesn't matter who's doing it."

Maz Ali, a 28-year-old dentist, is also sceptical. "I don't see the need for it to be here. It wouldn't change anything," she says.

'No impact'

Not that many people seem to be aware of how the GMCA works currently. In an unscientific survey of 20 people on the city's streets, just three said they had heard of it.

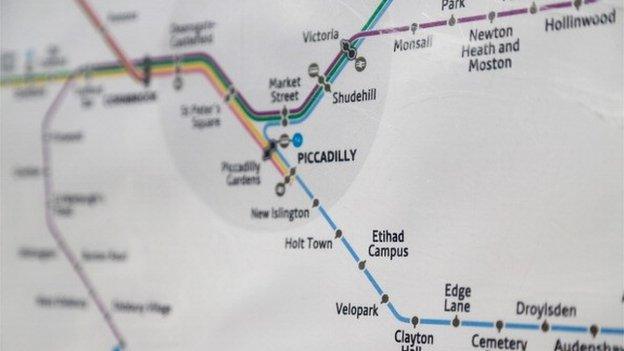

So far, the authority has focused its efforts on regenerating large areas such as Salford Quays and building a tram system that links Manchester to Salford, Eccles, Altrincham, Bury, Rochdale and Ashton-under-Lyne.

The authority has focused on the city's tram system

Some who have heard of the GMCA struggle to point to any difference it has made.

Phil Littlewood, 61, a semi-retired IT professional, says he doesn't think it's had any impact on his life. "Maybe it needs more time?" he suggests.

He likes the idea of local bodies having more control over their own budgets though, saying spending priorities should include funding for museums and improving the transport system.

Others - although unaware of the GMCA - nevertheless name-check its projects as things to admire about Manchester.

Margaret Walker, 75, says she finds the tram "very convenient", and Roma Swords, 21, says she loves the "city vibe" of the bars and shops in the northern quarter.

Of plans for a new mayor, Margaret likes the idea of "somebody that you knew was there and could write to if you wanted to". "Isn't Alex Ferguson looking for a job?" suggests Tony Nuttall.

Roma Swords credits the authority with creating a "city vibe" in the northern quarter

Funding for museums, such as Imperial War Museum North, is one source of concern for residents.

Colin Talbot, professor of government at Manchester University, says the GMCA has a "mixed record".

The authority's attempt to set up a congestion charge "went down like a tonne of bricks", he says, but it can be proud of the "vast improvement" offered by the tram and new recycling facilities.

'Massive imbalance'

He believes Manchester is a "good example of what you can do without electing a whole new set of politicians" and that "groups of different political persuasions work very well together".

That is something other areas should strive for, he argues, but in his view "the current discussion about devolution does not go far enough" and benefits payments and tax collection could be carried out locally.

Dr Stuart Wilks-Heeg, a politics expert from Liverpool University, also backs the idea of raising more revenue locally, but cautions that further devolution could get complicated.

"If you allow Manchester to collect stamp duty and capital gains tax, the case for allowing London to do it is irrefutable, which would create massive imbalance," he says.

"If you think the Barnett formula is a minefield, this would be a complete nightmare," he says.

Manchester is famous for its football teams, which have invested money in regeneration

As for whether other cities and regions should follow suit, he points out that the establishment of a similar combined authority on Merseyside "has not exactly gone smoothly".

"Each area has its peculiarities and it's important that we don't get a top-down approach," he says.

Prof Talbot foresees problems with the government's latest plans, pointing out that a North East assembly was rejected in 2004, and Manchester was one of 10 cities to vote "no" to the offer of an elected mayor in 2012.

He warns that Monday's announcement could be seen as an "imposition".

"Unless this is done through political consensus it could lead to even more instability in our system of local government, which we've had for nearly 40 years now with almost constant reorganisations," he says.

Whatever model of devolution English cities follow, it seems Manchester is first in line.

- Published3 November 2014

- Published22 October 2014

- Published15 September 2014

- Published4 May 2012