The story of the fake bomb detectors

- Published

The fake devices were used on checkpoints in Iraq at a time when bombs were killing or injuring thousands

The sentencing of a British couple for making fake bomb detectors marks the end of a series of trials after a global scam which saw the devices end up in conflict zones and used by governments around the world.

From the battle against suicide bombers in Baghdad, to the drug wars in Mexico and the campaign against poachers in Africa, the "magic wand" detectors were used to search for explosives, cocaine and smuggled ivory.

In southern Thailand, with its longstanding insurgency, they were deployed by the armed forces in security sweeps.

In Pakistan, they were used to guard Karachi airport. And around the Middle East they were bought to protect hotels.

They were all bogus. But despite this, some are still in use today - in Iraq at checkpoints, to guard sites in Pakistan, and at hotels in the Middle East.

Despite the sophisticated, expensive-looking packaging and glossy publicity, the devices were useless

The publicity and packaging cost more than the devices themselves. The fake "detectors" - sold with spurious but scientific-sounding claims - were little more than empty cases with an aerial which swings according to the user's unconscious hand movements, "the ideomotor effect".

Yet the scam lasted for years. It made British fraudsters millions of pounds - in thousands of sales across several continents.

And lives were put at risk.

Assembled in garden

The wand-like devices marketed by a Somerset-based businessman called James McCormick were used in Iraq, where detecting a bomb means the difference between life and death.

Between 2008 and 2009, for example, more than 1,000 Iraqis were killed in explosions in Iraq - thousands more were injured.

McCormick was jailed for 10 years last year and others followed - 47-year-old businessman Gary Bolton was convicted last August, Samuel Tree will now spend three and a half years in jail, while his wife received a suspended sentence.

The Bedfordshire couple bought cheap plastic parts from China and assembled the devices in a shed in their back garden.

Joan and Sam Tree made the Alpha 6 device in their garden shed in Dunstable in Bedfordshire.

The prototype for the device began life in the US as the Gopher - marketed as "the perfect gift for the golfer who has everything." The $20 (£12) plastic gadget claimed to use advanced technology, "programmed to detect the elements found in all golf balls".

"Had it stayed a golf ball finder, this would never have been an issue," says Det Con Joanne Law, who investigated the scam for City of London Police.

But - with the simple addition of a new label - the Gopher became the "Quadro Tracker" - and was sold by a former used car salesman to point out drugs and explosives. After the FBI declared it a fraud in 1996, a British man involved with the device brought the idea back to the UK, where the scam resurfaced as the "Mole."

The Gopher "amazing golf ball finder" sold for around $20 (£12)

Attempts were made to market the Mole to British government agencies and, in 2001, it was tested by Home Office scientist, Tim Sheldon.

He told the BBC that he issued the strongest possible warning about the device, in advice circulated to government departments.

"The claims that were made for it were completely misleading," he says. "We warned that it would be potentially dangerous to use."

He thought that would be the end of the story.

But the fraudsters behind the bogus detectors repackaged and renamed them yet again, seeking out new markets overseas - where fewer questions would be asked and where bribes could oil the wheels of lucrative deals.

The fraudsters and their devices

The ADE-651 (supposedly shorthand for Advanced Detection Equipment) was sold to Iraq, Niger and other Middle Eastern countries by Somerset-based businessman, James McCormick, who is now serving 10 years in jail. The Iraqis spent £53m ($85m) on the devices at around £5,000 ($8,034) a time. Some sold for as much as £25,000 ($40,178).

The GT200 "remote substance detector", sold by Gary Bolton mainly in Mexico, Thailand, the Middle East and Africa. The device retailed at £5,000 ($8,034) but the highest price it achieved was £500,000 ($803,000). Bolton was sentenced to seven years.

The Alpha 6 manufactured by Samuel and Joan Tree and sold to Egypt, Thailand and Mexico, usually at £2,000 ($3,213) per device. The highest sale price was £15,500 ($24,906) Tree was given three and a half years behind bars while his wife was ordered to do 300 hours unpaid community work.

"I was really surprised at the scale of it," says the City of London's Police's Det Con Joanne Law of the scam. "And I was shocked by the methods the suspects used to sell them."

Sales demonstrations would be rigged to succeed, she says. Anyone sceptical of the devices would be publicly humiliated. And users were instructed not to open the equipment - to avoid damaging the "sensitive technology" inside.

Gary Bolton was jailed last August

Some of the devices came with "detector cards" which were programmed, the fraudsters claimed, to detect everything from explosives, to human beings and dollar bills through concrete, water and from great distances.

'Embarrassing'

Fraudster Gary Bolton even charged the Royal Engineers thousands of pounds for useless cards that went missing from a trade fair at which uniformed members of the corps had been paid to help promote the bogus devices.

Bolton's device, the GT200, was also backed by British embassies in Mexico City and Manila, through the then Department of Trade and Industry.

"The involvement of UK government agencies in promoting this is very embarrassing and awkward," says Mr Sheldon, who was shocked to learn of the involvement of the Royal Engineers Exports Support Team.

"I really don't know how that could have happened. I think they should have checked with the experts that the device actually had some merit before they promoted it."

Police said Joan and Samuel Tree hired Bolton after meeting him at an arms conference

The government says it has since reviewed its procedures to make it clear the UK exhibiting equipment does not equate to an endorsement.

"When it becomes apparent that a company is making false claims, or the risk of this happening is significant, [UK Trade and Investment] will withdraw its support and refer matters to the appropriate authorities," a Cabinet Office spokesman says.

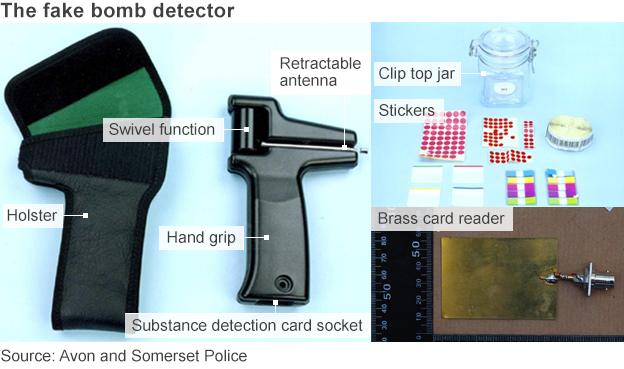

How McCormick's ADE-651 device was meant to work:

1. A small amount of the substance the user wished to detect - such as explosives - was put in a clip top jar along with a sticker that was intended to absorb the "vapours" of the substance

2. The sticker was then placed on a credit-card sized card, which was read by a card reader and inserted into the device

3. The user would then hold the device, which had no working electronics, and the swivelling antenna was meant to indicate the location of the sought substance

Neither the British nor American governments ever bought the device for themselves. But it took until 2010 for the UK government to bring in export controls - and then only to prevent its sale to Iraq and Afghanistan.

"Once it was established that they were rubbish, nonsense, completely useless pieces of junk that were being used to purportedly protect people from bombs and danger, there should have been an export ban immediately," says David Heath, Liberal Democrat MP for Somerset and Frome - where Jim McCormick is a constituent.

"The bizarre thing, as I understand it, is because it didn't work, it didn't have to have a licence. But no-one thought to mention that to the police, or to the Foreign Office and trade and industry people to stop them providing support.

"Someone somewhere made a big mistake," he says. "And I'd like to know who."

Five fraudsters have now been sentenced to jail terms over the bogus devices.

"It does exactly what it's designed to - it makes money," McCormick is said to have responded to concerns about his useless ADE-651.

"I would hope that that would put a stop to it now," says Tim Sheldon. "But I suspect it will re-appear in a few years - if it hasn't already."

In fact, earlier this year, the device surfaced in Egypt with claims from the Egyptian military that it could detect hepatitis and HIV.

And the bogus detectors are still in use at checkpoints across Baghdad. They were also deployed at a recent security conference in Djibouti and, just this week, the BBC filmed them in use at a shopping mall in Pakistan.

Astonishingly, perhaps, some officials still blame user error or even the weather for the device's failure to detect explosives.

Gen Saad Ma'an, from Iraq's Ministry of Interior, accepts the devices are not working "to the required level" but says the country is still waiting to replace them.

"Maybe it's affected by conditions - by the weather, by how the policemen themselves are using it," he says.

But the message from the British police is unequivocal: "They don't work, don't use them."

- Published3 October 2014