Does anybody still care about chess?

- Published

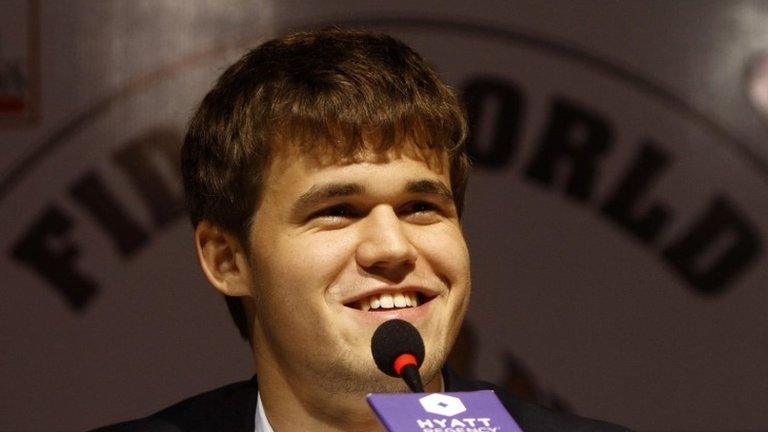

Magnus Carlsen has just beaten Vishy Anand in the World Chess Championship

In the summer of 1972, newspaper editors were not short of headlines.

Henry Kissinger was trotting around the globe as the US sought to extricate itself from Vietnam.

The Ugandan Asians were in flight, expelled by the mad, bad President of Uganda, Idi Amin.

Sectarian riots had broken out in Northern Ireland; Chile appeared to be heading towards anarchy.

And there was a burglary at the Watergate complex in Washington DC - the repercussions of which would soon bring down the president.

So there was no dearth of news.

Yet, holding an almost daily place on the front pages was a chess match in the tiny Icelandic capital of Reykjavik.

Never before or since has chess captured the world's imagination in quite this way.

It became known as "The Match of the Century".

At stake was the world crown.

Mesmerising personality

The two players were the Soviet champion Boris Spassky and the challenger Bobby Fischer.

Fischer's strident demands nearly torpedoed the contest and the fascination the match aroused owed much to his troubled, mesmerising personality.

Although in 1972 the US and the USSR were in a period of detente, Fischer was able to frame the match as the Cold War in microcosm.

He was a solitary American taking on the previously invincible Soviet chess machine.

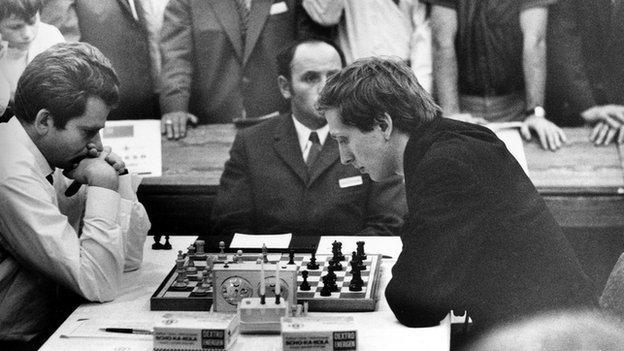

Spassky playing Fischer: Their world championship match was followed around the world

The Soviets had dominated chess since World War Two: For them chess was a tool in a wider propaganda war.

Over four decades later, and the world chess championship is again front page news.

At least it is in Norway.

That the Norwegians are gripped by this contest is understandable.

The current world champion is 23-year-old Norwegian Magnus Carlsen.

He has just beaten the Indian, Vishy Anand, himself a former champion, but who, at 44, is probably past his peak.

Carlsen first captured the crown from Anand only last year.

But while Carlsen's fortunes were followed in Norway by chess players and non-chess players alike, he is a less familiar figure outside the country.

Coverage of his retention of the world title was scant in the British media, and it hardly helped that the denouement came on the same day that Lewis Hamilton's secured the Formula One world drivers' championship.

In a recent episode of a British game show, Pointless, fewer people recognized Carlsen's name than that of the 1972 champion - Bobby Fischer.

This raises a puzzle. Why has the public profile of chess declined?

Political context

Football requires no grand political narrative to captivate spectators.

When Real Madrid play Barcelona, tens of millions watch around the world.

The rivalry between these teams has a rich history, but we do not need to understand much about this background to persuade us to turn on the TV.

It is enough that the game will feature some of the finest players in the world, and that the viewer can anticipate some dazzling skills.

But to break into the mainstream, chess has always needed to be framed within a wider political context.

The Fischer-Spassky match fuelled a worldwide chess mania.

There was a run on chess sets, prize money for competitions shot up, chess books proliferated.

This didn't last long, although subsequent title matches were still deemed newsworthy.

There was the ferocious rivalry between the loyal Russian communist Anatoly Karpov and the awkward dissident Victor Korchnoi, who sought political asylum in the West and whose name therefore became unmentionable in the USSR.

The non-chess world was enthralled by plots, both real and imaginary.

These included the allegation that when Karpov was sent a yogurt during the game, his team was using the fruit flavour to pass on a secret message.

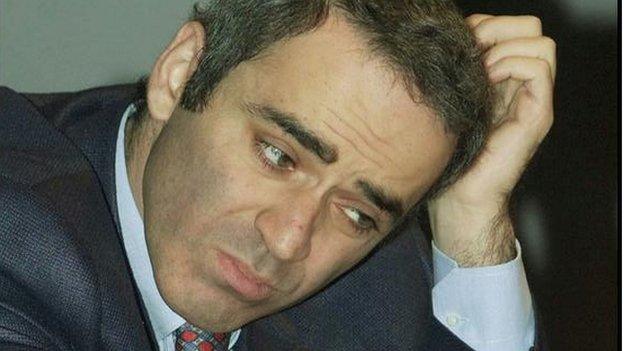

Karpov and Kasparov had several memorable duels

Later, after the Berlin Wall fell, and the Soviet Union imploded, the brilliant champion, Garry Kasparov, came to embody the new spirit of democracy, and of perestroika against Karpov, who listed Marxism as one of his hobbies.

The loss of a Cold War political narrative has not been the only blow to chess.

During the Fischer-Spassky match games were adjourned after five hours, and resumed later.

That would never happen now because computers would be used to calculate the best continuations. So once begun, games have to be played out to the end.

That's a relatively trivial way in which computers have revolutionised chess.

Pinnacle of chess

The real change has been a gestalt-shift in how the human competitor is viewed.

Nobody - and no thing - could compete at Fischer's level in 1972.

He represented the pinnacle of chess, its supreme exponent.

His mental powers seemed somehow magical, unfathomable.

And whilst at one level Carlsen's capacities are no less astounding - his rating, after all, is the highest in history - the aura has largely dissipated.

Garry Kasparov, a brilliant champion, was beaten by a computer

In 1997, an IBM computer, Deep Blue, beat Kasparov, the reigning champion.

Now, almost everyone could be smashed by their mobile phone.

Spectators know that a machine with Carlsen's position could find some stronger moves.

Indeed, any spectator can plug a grandmaster position into their computer to check for the best options.

Online following

As a result, the world champion has been transformed from a demi-god to a flawed and fallible mortal.

It would be a mistake, however, to be overly pessimistic about the future of chess.

The computer age has not been all bad for the game.

Recently the Sunday New York Times announced it was dropping its chess column. This was taken as a further sign of the demise of chess.

In fact, the internet has led to a migration from old forms of media to new.

People can now play speed chess with opponents on the other side of the world.

They can follow tournaments online: The London Chess Classic, a tournament that takes place each December, can attract nearly half a million followers.

The Carlsen-Anand game will be followed by millions.

A recent poll put the number of chess players in the world in the hundreds of millions.

What's more, there's no sign that computers are close to "solving" chess.

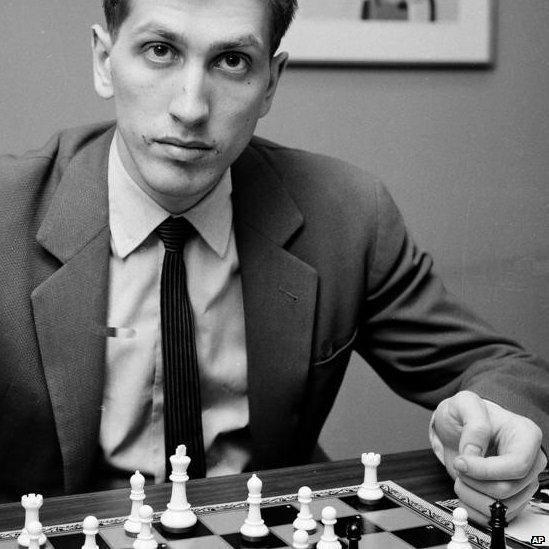

Bobby Fischer, seen here in 1962, is now just the 14th highest rated player of all time

If anything, silicon power has opened up fresh possibilities - showing that moves and strategies that might previously have been dismissed as obviously unsound are in fact viable.

Perhaps we shouldn't be surprised by these surprises.

There are more permutations in chess than there are atoms in the universe.

And it's the boundless complexity of the game that allows it to be a continual source of delight, wonder and, yes, beauty.

Chess has been around for centuries.

And if it doesn't capture the newspaper headlines these days, still, it has an enduring appeal.

Rumours of its death are greatly exaggerated.

Highest rated chess players:

1 Magnus Carlsen, May 2014

2 Garry Kasparov, July 1999

3 Fabiano Caruana, Oct 2014

4 Levon Aronian, Mar 2014

5 Viswanathan Anand, Mar 2011

6 Veselin Topalov,July 2006

7 Vladimir Kramnik, May 2013

8 Alexander Grischuk, Oct 2014

9 Teimour Radjabov, Nov 2012

10 Hikaru Nakamura, Jan 2014

11 Alexander Morozevich,July 2008

11 Sergey Karjakin, July 2011

13 Vassily Ivanchuk, Oct 2007

14 Bobby Fischer,Apr 1972

15 Anatoly Karpov, July 1994

- Published22 November 2013

- Published22 November 2013

- Published24 December 2013

- Published18 May 2012